It’s difficult now to reconstruct the order in which I discovered different writers in my teenage years. At 15 I started writing poetry. Reading serious literature began soon afterwards. I consumed it as quickly as I could, lurching between states of delirious absorption and brittle, snappish judgement. My boyhood reading, the Arthur C. Clarke or Ray Bradbury paperback on my bedside table, was displaced by a stack of books that contained Nabokov, Lowell, Yeats, Beckett, Dickens, Hardy, Larkin, Eliot, Carlos Williams, Joyce, Chekhov, Chatwin, Kafka, Heaney and on and on in quickly changing combinations. I do know that I read a few of Geoffrey Hill’s poems in an anthology of modern British poetry that we had at school and that an English teacher had mentioned him. This teacher had abandoned Cambridge and a Ph.D. on Hill and Larkin, and he spoke about both poets in the tones of someone recovering from too long an exposure to their powers and personalities: exasperated, overawed, mocking, proprietorial, affectionate.

I bought my copy of the King Penguin edition of Geoffrey Hill’s Collected Poems (1990) at Skoob Books, then located in Sicilian Avenue in Bloomsbury. Skoob was my bookshop and that journey from the suburban eastern reaches of the Central Line to Holborn was one that I made often. It transported me thrillingly into the sphere of art and literature where there were paintings to see and places where writers had walked and sunlight struck through the branches of plane trees between high and elegant façades and streets paused in meditation around squares with famous names and independent adults went about their lives. Sometimes in London I get again the feeling I had then, that freshness of setting out into a world already achieved and in place but inviting and mobile with possibility. When I do, I hear the opening of Stravinsky’s Violin Concerto – we had an LP of it at home listened to a lot at that time – that zest of enterprise and invention in an established form.

The book, a paperback, didn’t much resemble the other poetry books I had, most of which bore a portrait drawing of the poet beneath the title surrounded by the grid of double fs of Faber and Faber, a solemn sort of wallpaper that indicated serious literature inside. Hill’s poems had the size and feel of a novel. On the cover was Gauguin’s rendition of Jacob wrestling with the angel from his Vision after the Sermon. On the back, Hill himself scowled out from under a supremely confident comb-over in an author photograph with no hint of warmth or welcome. Licence was granted for this attitude by the words of praise around it, the first of which, from Michael Longley, declared, ‘He is a profound genius, the best poet writing in English.’ Other encomia came from the likes of George Steiner and Christopher Ricks. This was ideal. Profound genius was all I was interested in and the difficulty that my teacher and the cover copy warned me abo

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inChills, pastes, thrives, squeaks, gored, daubed. This particular quality satisfied a hunger in me for intensity, for something sensational, that generalized adolescent ardour which wants that contact with ‘weight and strength’ that Robert Frost yearns for in ‘To Earthward’. Hill’s senses were tuned mostly to register English landscapes in fine detail, things familiar and enhanced by the economical accuracy of his language:Against the burly I strode.

Each day the tide withdraws; chills us; pastes The sand with dead gulls, oranges, dead men.

A beast is slain. A beast thrives. Fat blood squeaks on the sand.

beasts With claws flesh-buttered.

before sleeked groin, gored head, Budge through the clay and gravel, and the sea Across daubed rock evacuates its dead.

OrThe twittering pipistrelle, so strange and close, plucks its curt flight through the moist eventide.

And this I knew very well, reading in the evenings in my bedroom at the top of a house beside Epping Forest:The dark-blistered foxgloves, wet berries Glinting from shadow, small ferns and stones.

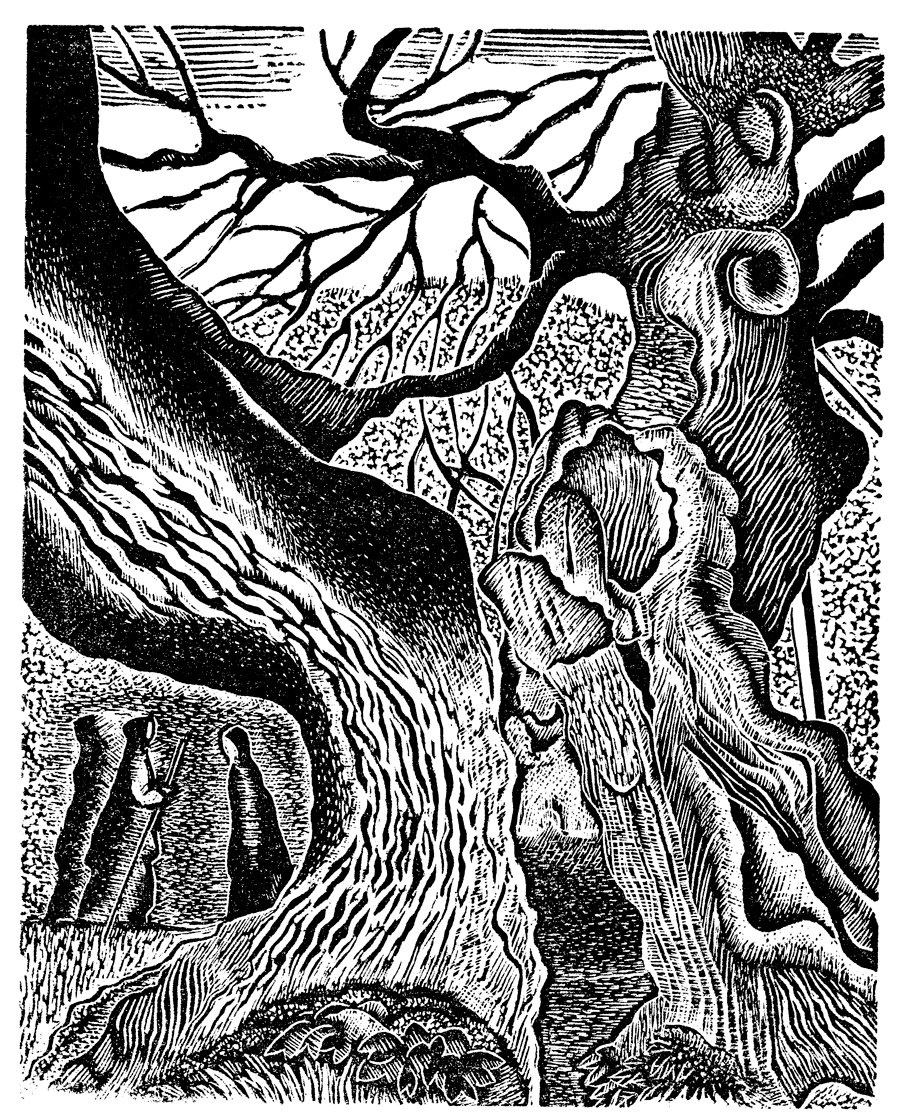

The tactile address of these poems, their furrowed and foliate English environments, often worked to substantiate feats of historical imagination, to make temporally distant scenes feel real. I found in this book a poet more interested than any other I’d read in writing about history in lyric poems. Medieval, Anglo-Saxon, Roman, Victorian subjects abounded. Beyond Hill’s descriptions giving physical solidity to his subjects, there was a sense in which historical presences were conjured into landscape in a way one might call psychogeographical. In what remains Hill’s greatest single work, Mercian Hymns, he braided intricacies of the Midlands countryside with the presence of the Anglo-Saxon king Offa and his sort of avatar in the figure of the twentieth-century boy-poet who ‘exchanged gifts with the Muse of History’.I leaned to the lamp; the pallid moths Clipped its glass, made an autumnal sound. Words clawed my mind as though they had smelt

Revelation’s flesh . . .

The boy-poet seems an autobiographical figure, sharing at least age and interests with Hill. He is someone who sees differently.The princes of Mercia were badger and raven. Thrall to their freedom I dug and hoarded. Orchards fruited above clefts. I drank from honeycombs of chill sandstone.

This idea, that the landscape can flow back to its source, that rapt attention can funnel us backwards into visionary historical encounter, is a conceit that the Mercian Hymns make credible with their tremendous artistic success, when really it exists at a limit of plausibility. It is only imaginative power, the Muse of History, which makes this possible. History is peculiar stuff. It happened. It was here and it explains the present moment. It is ungraspable at the same time that it is (must have been) maddeningly real. Hill’s Collected Poems display a number of the varying ways that attempting to write imaginative history can go, and I realize now that they have informed my own attempts to do so. Occasionally, Hill lapses into kitsch and there’s a touch of the historical pageant or the cyclorama, as in this moment after the Battle of Towton:Candles of gnarled resin, apple branches, the tacky mistletoe. ‘Look’ they said and again ‘look.’ But I ran slowly; the landscape flowed away, back to its source.

And sometimes that quality of artifice is self-conscious and makes a point about the simplification and mythologizing of history. I think that’s happening in this novelettish moment in a sequence that takes its title from Augustus Pugin’s pamphlet advocating Gothic Revivalism, ‘An Apology for the Revival of Christian Architecture in England’:dislodged, a few Feathers drifted across. Carrion birds Strutted upon the armour of the dead.

Hill’s historical writing often combines his knowledge with analysis and unforgettable linguistic pungency. Take this moment from one of three poems entitled ‘A Short History of British India’ in the same sequence:What an elopement that was: the hired chaise tore through the fir-grove, scattered kinsmen flung buckshot and bridles, and the tocsin swung from the tarred bellcote dappled with dove-smears.

The concentration is superb. ‘Indifferent’ suggests both incompetence and a lack of interest in differentiating possible victims, and raises the possibility that the firing is only a display of power. ‘Rutting’ mocks the phallic pomp of that display and visually conjures the back and forth movement of the guns between crenellations and brings the spectre of getting ‘stuck in a rut’ into view. It’s hard to imagine that two lines could better capture the coarse demonstrativeness and libidinal release in imperial violence as well as framing it within a final futility, the decline and fall of empires. Such moments disclosed to me, the teenage reader, clear vistas of historical perspective that helped shape my understanding of the world and taught me what language could make real. I loved the Collected Poems and years later my mind is still studded with many of its phrases. It is a book that is deep in the formation of my mind and when Hill died last year I felt it as a personal loss. The Collected Poems hasn’t so much influenced me as mapped out an extensive possible imaginative territory in which much of the time I still work. Like many readers, I prefer the poems of this Collected to the later volumes that followed because, in the end, it is to the landscapes that I return and they become intermittent in the argumentative long poems of more recent years. The landscapes have such presence and resonance and charisma. I remember now that I liked to take this book with me on the remaining family holidays of my teenage years and in the hot, empty geometry of sky and swimming pool, with crickets rasping in the coarse grass, I immersed myself in Hill’s perfected England, his rich images standing out in high contrast.with indifferent aim unleash the rutting cannon at the walls of forts and palaces.

Autumn resumes the land, ruffles the woods with smoky wings, entangles them. Trees shine out from their leaves, rocks mildew to moss-green; the avenues are spread with brittle floods.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 55 © Adam Foulds 2017

About the contributor

Adam Foulds is a poet and novelist.