I first came across Ahmed Hassanein Bey when bumping across the Libyan Sahara by camel with a friend. This was long before Kindles and iPads helped the bibliophile traveller lighten his load. Between us we had a slightly hodgepodge library consisting of a Koran, a New Testament (a Christmas present from my mother, inscribed with Deuteronomy 2:7: ‘The Lord your God has blessed you in all the work of your hands. He has watched over your journey through this vast desert’), some Oscar Wilde short stories, P. G. Wodehouse, Trollope, the complete works of Shakespeare, a volume of poetry, Homer’s Odyssey and an Arabic language book. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom and Hassanein Bey’s The Lost Oases completed the collection to be borne across the desert by our diminutive caravan of five camels: Asfar, Gobber, The Big White, Bobbles and Lebead.

Thank goodness for The Lost Oases. It tells the story of a truly epic journey of 2,200 miles by camel from the tiny Egyptian port of Sollum on the shores of the Mediterranean to Al Obeid in what was, in 1923, Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. As leader of this remarkable seven-month expedition, which discovered the ‘lost’ oases of Jebel Arkenu and Jebel Ouenat, Hassanein Bey was awarded the Founder’s Medal by the Royal Geographical Society in 1924. The director of the Desert Survey of Egypt hailed it as ‘an almost unique achievement in the annals of geographic exploration’.

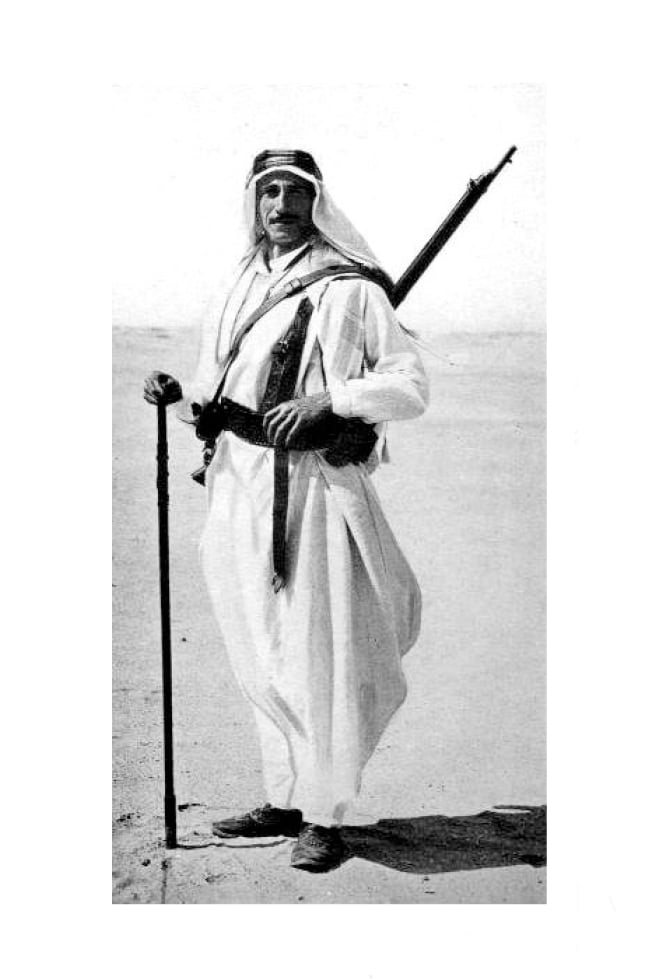

Hassanein Bey is the perfect guide to the Sahara, whether for an armchair enthusiast or desert traveller. Born in 1899, he was the son of the Sheikh of Al-Azhar, Egypt’s equivalent of the Archbishop of Canterbury, and grandson of the last Admiral of the Egyptian fleet. Educated at the University of Cairo and at Oxford, where he won a fencing Blue, he served as Arab Secretary to the British Co

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inI first came across Ahmed Hassanein Bey when bumping across the Libyan Sahara by camel with a friend. This was long before Kindles and iPads helped the bibliophile traveller lighten his load. Between us we had a slightly hodgepodge library consisting of a Koran, a New Testament (a Christmas present from my mother, inscribed with Deuteronomy 2:7: ‘The Lord your God has blessed you in all the work of your hands. He has watched over your journey through this vast desert’), some Oscar Wilde short stories, P. G. Wodehouse, Trollope, the complete works of Shakespeare, a volume of poetry, Homer’s Odyssey and an Arabic language book. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom and Hassanein Bey’s The Lost Oases completed the collection to be borne across the desert by our diminutive caravan of five camels: Asfar, Gobber, The Big White, Bobbles and Lebead.

Thank goodness for The Lost Oases. It tells the story of a truly epic journey of 2,200 miles by camel from the tiny Egyptian port of Sollum on the shores of the Mediterranean to Al Obeid in what was, in 1923, Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. As leader of this remarkable seven-month expedition, which discovered the ‘lost’ oases of Jebel Arkenu and Jebel Ouenat, Hassanein Bey was awarded the Founder’s Medal by the Royal Geographical Society in 1924. The director of the Desert Survey of Egypt hailed it as ‘an almost unique achievement in the annals of geographic exploration’. Hassanein Bey is the perfect guide to the Sahara, whether for an armchair enthusiast or desert traveller. Born in 1899, he was the son of the Sheikh of Al-Azhar, Egypt’s equivalent of the Archbishop of Canterbury, and grandson of the last Admiral of the Egyptian fleet. Educated at the University of Cairo and at Oxford, where he won a fencing Blue, he served as Arab Secretary to the British Commanding Officer in Cairo during the First World War. Later he became an adviser to King Fuad and tutor to Prince Farouk. He also represented Egypt at fencing in the Olympics of 1920 and 1924. Good as T. E. Lawrence undoubtedly is – and he takes some beating as a writer on the desert – Hassanein Bey brings an extra quality to his literary travels. He may be a hugely urbane (and urban) sophisticate, but he is no infidel outsider. He does not need to be an accomplished Arabist or Orientalist because he speaks Arabic as an Arab, and he shares the faith, albeit less fatalistically, of those among whom he travels. Perhaps more important than any of this for Slightly Foxed readers, he writes like a dream. As he sets off he ponders the allure of the desert. ‘It is as though a man were deeply in love with a very fascinating but cruel woman. She treats him badly, and the world crumples in his hand; at night she smiles on him and the whole world is a paradise.’ He is completely smitten. Like all good explorers, he ignores advice from the doomsayers. A rich merchant from the Zawya tribe warns him not to travel south from Kufra:This journey you propose to make is through territory where no Beduin has passed before. The daffa [waterless trek] between Ouenat and Erdi is a long and hazardous one. God be merciful to the caravan in such heat. Your camels will drop like birds before the hot south winds.

Some of his camels do drop, a loss which affects him keenly. Hassanein Bey is a humane explorer whose guidelines for desert travel remain essential reading almost a century after he wrote them. Before I left for Libya, I consulted a Royal Geographical Society publication on desert navigation. The Lost Oases was the literary supplement.

‘Nothing is more important in trekking than the condition of your camels,’ Hassanein Bey writes. ‘Not only must they be fat and well nourished at the start, but they must be allowed to drink their fill with deliberation and permitted to rest after the drinking.’ Leaving the Libyan oasis of Jalo, he remarks that a sense of humour is ‘almost if not quite the most valuable asset in desert travel’. It’s an asset he certainly possesses. Whoever described the stomach-tightening cravings that assail the plodding desert traveller more amusingly than Hassanein Bey? Approaching Kufra, his mind wanders to elusive delicacies.

As I stride along I imagine myself in Shepheard’s Grill Room in Cairo and I order Crevettes à l’Americaine with that subtle variation of Riz à l’Orientale which is a speciality of the house. Or I am at Prunier’s in Paris ordering Marennes Vertes d’Ostende, followed by a steak and soufflé. Perhaps it is the Cova at Milan and a succulent dish of Risotto alla Milanese; maybe Strawberries Melba at the Ritz in London . . .

His reverie is rudely interrupted by a man passing him a handful of wizened dates.

Sometimes Christian travellers in Muslim lands get the wrong end of the stick when it comes to religion. This was particularly true in the nineteenth century, when British travellers like James Richardson, a Christian campaigner against the slave trade, dismissed much Islamic practice as blind superstition. Hassanein Bey does not fall into this trap. Although ordinarily he inhabits a world very far removed from that of the uneducated desert tribesmen, he shows a deep empathy with their religious rituals.

Our small caravan broke up once after a serious disagreement with our septuagenarian Tubbu guide, a descendant of the troglodyte Ethiopians praised by Herodotus as being ‘by far the swiftest of foot’ of any nation. We should have listened more carefully to Hassanein Bey, who explained the strict hierarchy of the desert caravan.In the desert, prayers are no mere blind obedience to religious dogma, but an instinctive expression of one’s inmost self. The prayers at night bring serenity and peace. At dawn, when new life has suddenly taken possession of the body, one eagerly turns to the Creator to offer humble homage for all the beauty of the world and of life, and to seek guidance for the coming day. One prays then, not because one ought, but because one must.

These days, with the profoundly unromantic accessories of satphones and GPS devices, the desert traveller is unlikely to be dicing with death. When Hassanein Bey undertook his journey, it was a distinct possibility. He caught the tribesmen’s approach to the ultimate adversity wonderfully well in the following passage:It is the etiquette of the desert that no one may interfere with the guide in any way. The guide of a caravan is exactly like the captain of a ship. He is absolute master of the caravan so far as direction is concerned, and must also be consulted as to the starting and halting times.

The highlight of Hassanein Bey’s astonishing journey was the discovery at Ouenat of 10,000-year-old cave paintings of lions, giraffes, ostriches, cows and gazelles created at a time when the Sahara was covered with wetlands. In one cave there were pictures of people swimming, a discovery later made famous by the film of The English Patient. This expedition was Hassanein Bey’s last as an explorer. His political career continued apace until 1946, when he was tragically killed in a car accident. Every page of The Lost Oases carries the unchecked passion for the desert of this most romantic, erudite and humane of writers, who perhaps better than anyone captures the paradox of this haunting wasteland: ‘The desert is terrible and merciless, but to the desert all those who once have known it must return.’The desert can be beautiful and kindly, and the caravan fresh and cheerful, but it can also be cruel and overwhelming, and the wretched caravan, beaten down by misfortune, staggers desperately along. It is when your camels droop their heads from thirst and exhaustion – when your water supply has run short and there is no sign of the next well – when your men are listless and without hope – when the map you carry is a blank, because the desert is uncharted – when your guide, asked about the route, answers with a shrug of the shoulders that God knows best . . . it is then that the Beduin feels the need of a Power bigger even than that ruthless desert. It is then that the Beduin, when he has offered his prayers to this Almighty Power for deliverance, when he has offered up his prayers and they have not been granted, it is then that he draws his jerd around him, and sinking down upon the sands awaits with astounding equanimity the decreed death. This is the faith in which the journey across the desert must be made.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 34 © Justin Marozzi 2012

About the contributor

Justin Marozzi is the author of South from Barbary: Along the Slave Routes of the Libyan Sahara. He is writing a history of Baghdad but would rather be back in the desert.