The trouble with memoirs is that too often they are written by people whose idea of what’s interesting is not the same as the reader’s. They are either grossly self-serving, like most political memoirs, or a good story spoiled by bad writing. Autobiography is not easy: it calls for literary talent, professional detachment and moral courage.

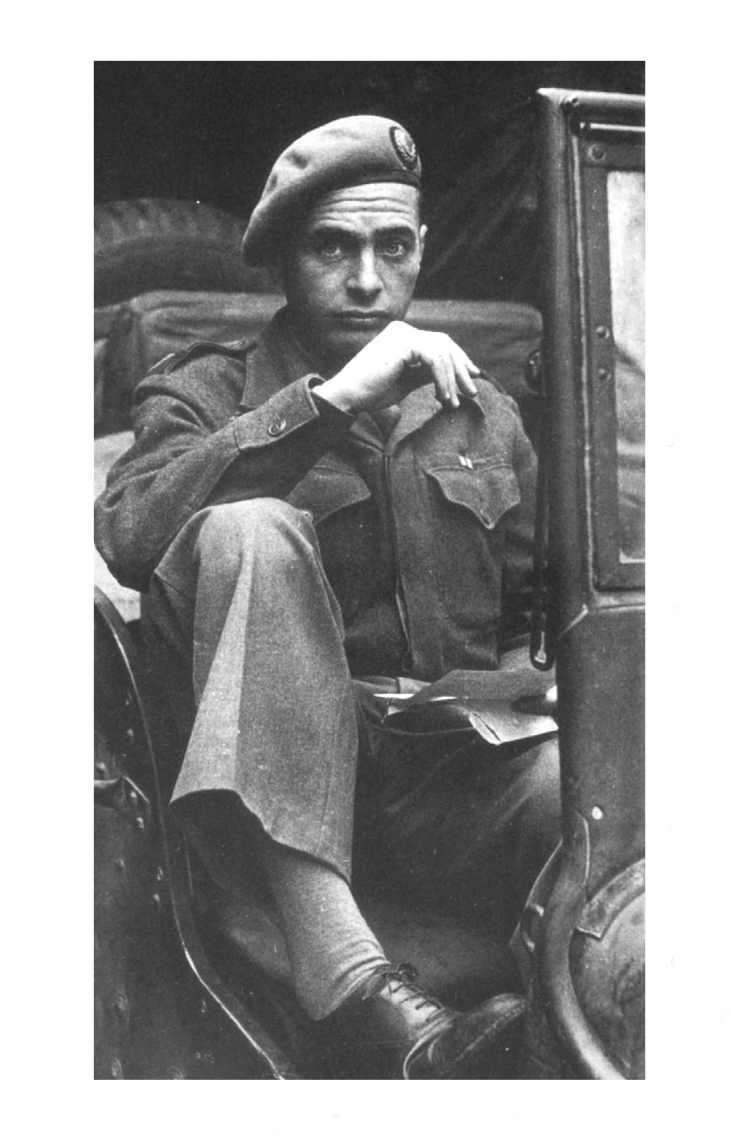

Alan Moorehead had all three. Not only was he a rare example of a high-profile newspaper reporter who turned himself into a bestselling author, but he also had the vital extra ingredient of critical self-awareness. The result is an unusually good autobiography.

Fortunately for us, Moorehead had drafted A Late Education: Episodes in a Life before being incapacitated by a severe stroke at the age of 56 which left him unable to speak or write properly and reading only with difficulty. His wife Lucy Milner was also a journalist (they had met at the Daily Express where she was woman’s editor) and she took on the job of editing her husband’s draft for publication in 1970.

The heart of the book is the friendship between Moorehead and his fellow war correspondent Alex Clifford of the Daily Mail. Professional rivals and temperamental opposites, they first met in a bar in St Jean de Luz in 1938 and didn’t hit it off. Meeting again in an Athens hotel in 1940, however, they found common ground and, having persuaded their respective newspapers to post them to Cairo, went through the rest of the Second World War together, from the Western desert, through Italy to Normandy and Paris.

The two were a perfect contrast. Alex was highbrow, diffident, well-educated, musically precocious and polyglot, but also indecisive, sexually shy and practically vegetarian. In describing his friend, Alan could see how very different he was himself: an energetic and ambitious young Australian, ‘aggressive, erratic and full of enthusiasms’, and in those days careless of others. Even physically they were op

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inThe trouble with memoirs is that too often they are written by people whose idea of what’s interesting is not the same as the reader’s. They are either grossly self-serving, like most political memoirs, or a good story spoiled by bad writing. Autobiography is not easy: it calls for literary talent, professional detachment and moral courage.

Alan Moorehead had all three. Not only was he a rare example of a high-profile newspaper reporter who turned himself into a bestselling author, but he also had the vital extra ingredient of critical self-awareness. The result is an unusually good autobiography. Fortunately for us, Moorehead had drafted A Late Education: Episodes in a Life before being incapacitated by a severe stroke at the age of 56 which left him unable to speak or write properly and reading only with difficulty. His wife Lucy Milner was also a journalist (they had met at the Daily Express where she was woman’s editor) and she took on the job of editing her husband’s draft for publication in 1970. The heart of the book is the friendship between Moorehead and his fellow war correspondent Alex Clifford of the Daily Mail. Professional rivals and temperamental opposites, they first met in a bar in St Jean de Luz in 1938 and didn’t hit it off. Meeting again in an Athens hotel in 1940, however, they found common ground and, having persuaded their respective newspapers to post them to Cairo, went through the rest of the Second World War together, from the Western desert, through Italy to Normandy and Paris. The two were a perfect contrast. Alex was highbrow, diffident, well-educated, musically precocious and polyglot, but also indecisive, sexually shy and practically vegetarian. In describing his friend, Alan could see how very different he was himself: an energetic and ambitious young Australian, ‘aggressive, erratic and full of enthusiasms’, and in those days careless of others. Even physically they were opposites: Alan was small, Alex large. Those who know Moorehead from Gallipoli, which launched his career as an author, or The White Nile, his most celebrated book, may be surprised by the character who emerges from A Late Education. A typical journalist, and the son of a journalist, he began his career on the Melbourne Herald but was desperate to get out of Australia. Bright rather than clever, energetic but not sporty, he was bottom of the class at school. His spelling was bad but his memory was good and he had – most importantly – a good ‘nose’. In those days journalism was a trade, not a profession, and it was not a fashionable career. Writing and spelling didn’t count so much as curiosity about the world and a sceptical view of authority, with perhaps a touch of missionary zeal. It was a job which attracted misfits like Alan and Alex – misfits of a different kind – who preferred to watch the game of life from the touchline rather than join the scrum on the field. Journalists, in Moorehead’s words, ‘opt out of normal life because they choose to write about it’. Yet they live just as hard and quite often get killed for their pains. Scenes from Moorehead’s life are interspersed, but not in chronological order, with episodes describing the two friends at war. The latter are ironically titled ‘To the Edgware Road’, because Alex Clifford had a morbid notion that he would die in that shabby London shopping street which, says Moorehead, ‘represented for him a way of life which he instinctively feared and loathed’. Arriving in London in 1936, the young reporter found himself at last in a place where the news was not only being read but also made. A torrid affair with the exciting but unreliable ‘Katherine’ did not prevent him from setting off on his travels – and his late education. First he went as a freelance to Spain to look at the civil war, and was quickly thrown out. He dropped in to Berlin for the Olympic Games and left a wonderfully mocking description of the Nazi fantasy concocted around them. The road to the stadium was lined with ‘statues of the young demi-gods and goddesses . . . great bull-like young men with truculent sexual parts and huge-bellied women carrying sheaves of wheat’. The eyes of the girl he was chatting up on the street took on a look of ecstasy when Hitler suddenly appeared through ‘a forest of outstretched arms’. And the Olympic village resembled nothing so much as a stud farm where pampered young stallions with oiled skins paraded around a compound, watched through the iron gates by German girls with nostrils flaring like mares aroused. The next year he was sent to Gibraltar, a ‘hot and ugly little town’, from which he escaped by embarking on a mission to discover who was sinking the ships running supplies from Turkey to the Spanish Republican cities along the coast. In Istanbul he boarded the cargo ship Tinos, carrying 8,000 tons of petrol, and after fighting off the homosexual advances of the huge and drunken captain, survived to witness a storm whose prelude he describes in words which Conrad might have envied:There followed an interlude in Paris, and the trip to St Jean de Luz on the Spanish border where he first met Alex Clifford, and where he saw the first column of Republican refugees coming over the Pyrenees. The first year of the war in North Africa was the best time. Moorehead loved the desert because it reminded him of the Outback. (The cultured Alex much preferred Italy.) Desert war was confusing, however, like a game of chess on a board with no squares and no edges. But it was civilized: there were no civilians to be bombed or raped, no villages to be razed, no ‘collateral damage’. Each day was the same. There was an hour of grace in the morning ‘when the sky was filled with a cool apple-green light, but then the sun lifted its mad glaring eye over the horizon and the sense of dread returned’. Fear of death affected the friends differently. Alan would go eagerly to the front but was afraid when he got there. Alex was jumpy on the way up, but appeared calm on arrival. On one of their many sorties, both very nearly lost their lives when their convoy drove into an Italian ambush in Cyrenaica. For most soldiers, the shortage of amusements in the desert had an antiseptic effect so strong that even lust was tamed. Life was entirely directed towards a higher end, the defeat of the Nazi tyranny. Moorehead saw his existential problems suddenly resolved: the past was over, the whole world was in flux, and no one knew what the future held. For recreation, everyone went to Cairo, a comic city where camels carried hurricane lamps on their tails. It was the last chance saloon. People plunged into a frenzy of dissipation, the men hypnotized by belly dancers in the nightclubs and the women gobbling cream cakes at Groppi’s. After the war, when Alex went on to greater things as a journalist, Alan gave up his job on the Express and retreated to Italy to become a writer. Here, living outside Florence, he enjoyed a further education. Improbably, he became the pupil and confidant of his neighbour, the elderly art historian Bernard Berenson. Tiny and frail, Berenson was strong-willed and had an encyclopaedic memory. He invited his new protégé to use the library at his villa, I Tatti, as a study. But he refused to talk about art. Another cultural celebrity befriended in Italy was only too keen to discuss his work. Festooned with cartridge belts, carrying strings of dead teal and mallard round his neck, and with snow dusting his beard and woolly hat, Ernest Hemingway first appeared as ‘the walking myth of himself ’. The two men sat together for several days, talking of nothing but books and writing. Hemingway contradicted his public image, however: he was lonely, shy of publicity, and in the throes of writer’s block. A Late Education ends with the premature death of Alex from cancer in 1952, after the two friends had taken a final, wild and joyous ski run down the mountain at Kitzbühel. Clifford did not die in the Edgware Road, as he had feared. But he did lie there: it was where they took his body, to the mortuary. Why are these memoirs so satisfying? Not because they describe great events or great personages, but because they are so expertly done. This is not the ‘colour’ writing of a well-paid hack but real prose. The stories are not tailored for posterity to show their author in the best possible light; they appear to have been dashed off – albeit with the help of diaries – in the heat of the moment. Although they have been chosen to give us a flavour of the man, they are mainly about his times. Moorehead, for all his reputed pushiness, is unusually modest. Rarely does one find an observer so observant about himself.I shivered on the bridge. All that concentrated heat from the iron decks had vanished, and the clean cold wind was rushing into every cranny of the ship, routing out the stale air and all the congested human smells we had brought from the Middle East. The sky was not yet entirely overcast. At several places where the flying clouds wore thin great rifts opened up, and looking through into the limpid cobalt space beyond we could see the new moon lying on its back, serene and yellow. For a minute or two it played a sickly light on the surface of the sea and the tossing bows of the Tinos, and then the clouds rushed across again, blotting it out with the rapidity and the completeness of a camera shutter.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 35 © Christian Tyler 2012

About the contributor

Christian Tyler is a former journalist. He worked for the Financial Times for 30 years.