Starting a story with ‘Once upon a time’ does not guarantee a happy ending. In their classic collection of folk tales, the rather aptly named Brothers Grimm made sure there was a moral to every story: goodness is rewarded, evil is punished, sometimes quite brutally. Even Hans Christian Andersen’s stories do not all end happily ever after: the prince who disguised himself as a swineherd to test the princess’s devotion came to despise her and returned alone to his own little kingdom.

Many celebrated authors have tried their hand at fairy tales, with varying degrees of success. In 1888 Oscar Wilde wrote Stories for Children which included such classics as ‘The Happy Prince’, but they are really not intended for children. Instead of ending happily ever after they tend to close with an epigrammatic punchline, like the one that concludes ‘The Devoted Friend’:

‘I told him a story with a moral’ answered the linnet. ‘Ah, that is always a very dangerous thing to do,’ said the duck. And I quite agree with her.

Even his classic fable ‘The Nightingale and the Rose’ ends on a note intended not for children but perhaps for the members of Lady Windermere’s fan club:

‘What a silly thing love is,’ said the student . . . ‘I shall go back to Philosophy and Metaphysics.’

A. A. Milne recognized this difficulty in the introduction to his delightful Once on a Time, published in 1917:

This is not a children’s book. I do not mean by that . . . ‘Not for children’, which has an implication all its own . . . This is a fairy story for grown-ups.

Children prefer incident to character; if character is to be drawn, it must be done broadly, in tar or whitewash. Read the old fairy stories, and you will see with what simplicity, with what perfection of me

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inStarting a story with ‘Once upon a time’ does not guarantee a happy ending. In their classic collection of folk tales, the rather aptly named Brothers Grimm made sure there was a moral to every story: goodness is rewarded, evil is punished, sometimes quite brutally. Even Hans Christian Andersen’s stories do not all end happily ever after: the prince who disguised himself as a swineherd to test the princess’s devotion came to despise her and returned alone to his own little kingdom.

Many celebrated authors have tried their hand at fairy tales, with varying degrees of success. In 1888 Oscar Wilde wrote Stories for Children which included such classics as ‘The Happy Prince’, but they are really not intended for children. Instead of ending happily ever after they tend to close with an epigrammatic punchline, like the one that concludes ‘The Devoted Friend’:‘I told him a story with a moral’ answered the linnet. ‘Ah, that is always a very dangerous thing to do,’ said the duck. And I quite agree with her.Even his classic fable ‘The Nightingale and the Rose’ ends on a note intended not for children but perhaps for the members of Lady Windermere’s fan club:

‘What a silly thing love is,’ said the student . . . ‘I shall go back to Philosophy and Metaphysics.’A. A. Milne recognized this difficulty in the introduction to his delightful Once on a Time, published in 1917:

This is not a children’s book. I do not mean by that . . . ‘Not for children’, which has an implication all its own . . . This is a fairy story for grown-ups. Children prefer incident to character; if character is to be drawn, it must be done broadly, in tar or whitewash. Read the old fairy stories, and you will see with what simplicity, with what perfection of method, the child’s needs are met. Yet there must have been more in Fairyland than that . . . Princes were not all good or bad; fairy rings were not always helpful. Is it a children’s book? Well, what do we mean by that? Is The Wind in the Willows a children’s book? Is Alice in Wonderland? Is Treasure Island? These are masterpieces which we read with pleasure as children, but with how much more pleasure when we are grown-up.In Milne’s story, King Merriwig of Euralia is having breakfast with his charming daughter Princess Hyacinth when they are rudely disturbed by something passing over the castle, not just once but eighteen times. It is the King of neighbouring Barodia trying out his birthday present, a pair of seven-league boots, and displaying a lamentable lack of good manners which calls for the composition of a Stiff Note. King Merriwig is interrupted in this task by the beautiful but ambitious Countess Belvane, who has ‘a passion for diary-keeping and the simpler forms of lyrical verse’:

The chronicler acknowledges that ‘many years after, another poet called Shelley plagiarized the idea, but handled it in a more artificial, and, to my way of thinking, decidedly inferior manner’. Any fairy story with a princess must have a prince, and while her father is away at the inevitable war with Barodia, Hyacinth writes to Prince Udo of Araby, who might be able to advise her on affairs of state which are being taken over by the literary Countess. Unfortunately the Prince is bewitched on his way to Euralia, and arrives at the castle with the head and long ears of a rabbit, the mane and tail of a lion, and the mid-section of a woolly lamb: ‘so undignified, so lacking in true pathos, and not even a whole rabbit’. Meals present a problem: they discover that he likes watercress sandwiches, which seem to go with the ears, but don’t suit the tail. The story is beautifully told: there are all sorts of subplots and complications before the essential but unusual happy ending, enlivened on occasion by the Countess’s regrettable lapse into anapestic trimetres:Hail to thee blythe linnet, Bird thou clearly art, That from bush and in it Pourest thy full heart.

Prince Udo, so dashing and bold Is apparently eighteen years old. It is eighteen years since This wonderful Prince Was born in the Palace, I’m told.

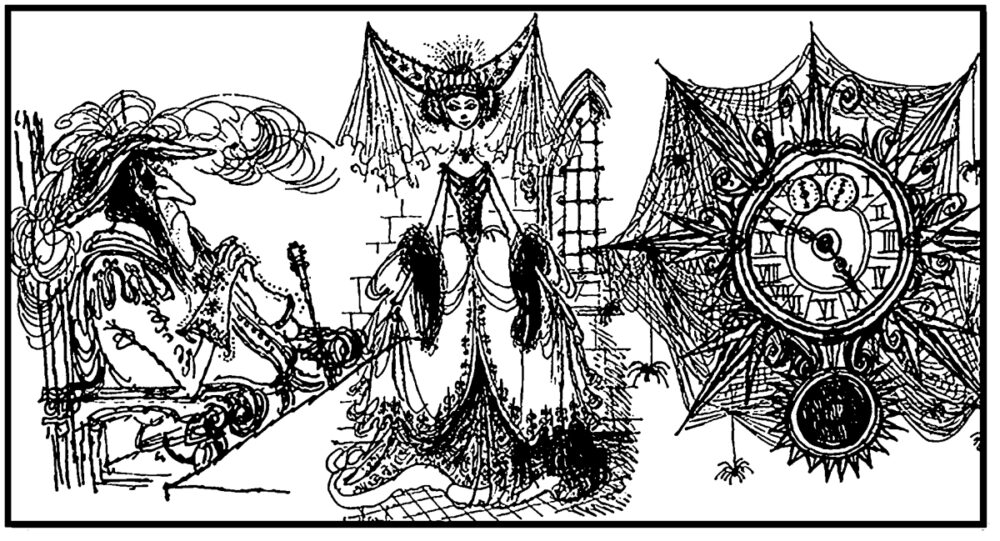

and her final diary entry: ‘September 15th. Became good.’ In Milne’s own words: ‘Read in it what you like; read it to whomever you like . . . either you will enjoy it or you won’t. It is that sort of book.’ James Thurber is probably best known for The Secret Life of Walter Mitty and the articles and cartoons he produced for the New Yorker, but he too ventured into the realm of fairy tales in 1950 with his fable The 13 Clocks, which he created ‘when he was supposed to be writing something quite different, because he couldn’t help himself’. It has all the elements of the classic fairy tale but is full of Thurber’s own literary idiosyncrasies: his love of words, which he invents when there aren’t any that quite suit his purpose, his sometimes macabre sense of humour, and his tendency to lapse into verse when a rhyme or alliteration distracts him. Ronald Searle’s illustrations complement the story – quirky and odd as usual, but perfect for this tale, studded as it is with puns and sly allusions: Once upon a time in a gloomy castle on a lonely hill where there were thirteen clocks which would not go, there lived a cold aggressive Duke and his niece, the Princess Saralinda. The clocks had frozen on a snowy night ten years before and it is always ten minutes to five in the castle: ‘It’s always Then. It’s never Now.’ The Duke limps and cackles through the cold corridors, planning impossible new feats for the suitors of the beautiful Saralinda who ‘wore serenity brightly like a rainbow’. Many princes and other suitors came and tried and failed and disappeared and never came again. And some, as I have said, were slain for using names that start with X, or dropping spoons, or wearing rings, or speaking disrespectfully of sin. The cold Duke is six feet four and 46 and even colder than he thinks he is. He has an invisible spy called Whisper, and is afraid of nothing except the Todal, which ‘looks like a blob of glup . . . makes a sound like rabbits screaming, and smells of old unopened rooms’. One day a wandering minstrel, quite properly ‘a thing of shreds and patches’, comes into town, courting the Princess and disaster with his songs:Hark, hark, the dogs do bark The Duke is fond of kittens. He likes to take their insides out, And use their fur as mittens.

The minstrel (who of course turns out to be a prince) is arrested and taken to the castle, where he is given an impossible task: to find a thousand gems in ninety-nine hours. If he fails the Duke will slit him from his guggle to his zatch and feed him to the geese. Fortunately he has some rather dubious help from the Gollux, who wears an indescribable hat and is somewhat unreliable, as he admits: ‘I make mistakes, but I am on the side of good by accident and happenchance.’ They set off on their seemingly hopeless quest through an alliterative jungle of assonance where ‘thorns grew thicker and thicker in a tricky thicket of bickering crickets’ and many other trials, in order to find a maiden who once was known to weep jewels when she heard a truly tragic story. Alas, she is unmoved by the plight of the Prince and the sad tales of the Gollux, so something else must be attempted if he is not to discover the location of his guggle and his zatch the hard way. Should we then conclude that there are two types of fairy stories, one for children and one for grown-ups? A difficult question, but T. H. White may have suggested an answer in The Sword in the Stone (1938). The Wart, who will grow up to be King Arthur, did not know what Merlin was talking about, but he liked him to talk. He did not like the grown-ups who talked down to him like a baby, but the ones who just went on talking in their usual way, leaving him to leap along in their wake, jumping at meanings, guessing, clutching at new words, and chuckling at complicated jokes as they suddenly dawned. He had the glee of the porpoise then, pouring and leaping through strange seas. Perhaps one reason Milne’s own stories have been favourites for so long is because he recognized this: surely Piglet’s legendary uncle Trespassers W and Owl’s Spotted or Herbaceous Backson are there not for the children, but for the grown-ups who take such pleasure in reading and rereading them the timeless tales.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 76 © Alastair Glegg 2022

About the contributor

Alastair Glegg lives on Vancouver Island and, like Molière’s bourgeois gentilhomme, is delighted to learn that when he thinks he is just writing rude limericks he is actually composing anapestic trimetres.