My grandfather taught me how to light a fire. I remember crouching by his side in the sitting-room on cold mornings, watching his huge hands crunching the paper, piling up the kindling, slotting the logs into place and lighting a match.

After the flare of the match, a few moments of silence. Then a glow, a flicker, a thin tongue of flame curling at the paper’s edge, sliding up a length of kindling, touching the bark, then slipping back into the little cave of orange light in the middle of the pile. It was my job to watch it didn’t go out, while he went to see to the cows. I crouched, and watched.

There’s an essay in Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac (1949) that brought me back to that moment:

My dog does not care where heat comes from, but he cares ardently that it come, and soon. Indeed he considers my ability to make it come as something magical, for when I rise in the cold black pre-dawn and kneel shivering by the hearth making a fire, he pushes himself blandly between me and the kindling splits I have laid on the ashes, and I must touch a match to them by poking it between his legs.

It’s one of those times when a book transports you instantly into a memory: conjuring the feelings, the smells, the sounds of a brief, vivid moment of childhood. I was there again, with my grandfather, but this time feeling very much like the dog that Leopold describes: silent, expectant.

A Sand County Almanac, and Sketches Here and There is a collection of Leopold’s writing from the 1930s and 1940s. Author, scientist, ecologist, forester, conservationist and environmentalist, Leopold was truly a powerhouse of natural history. His Sand County had a profound impact on the environmental movement, introducing the idea of wilderness management and environment

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inMy grandfather taught me how to light a fire. I remember crouching by his side in the sitting-room on cold mornings, watching his huge hands crunching the paper, piling up the kindling, slotting the logs into place and lighting a match.

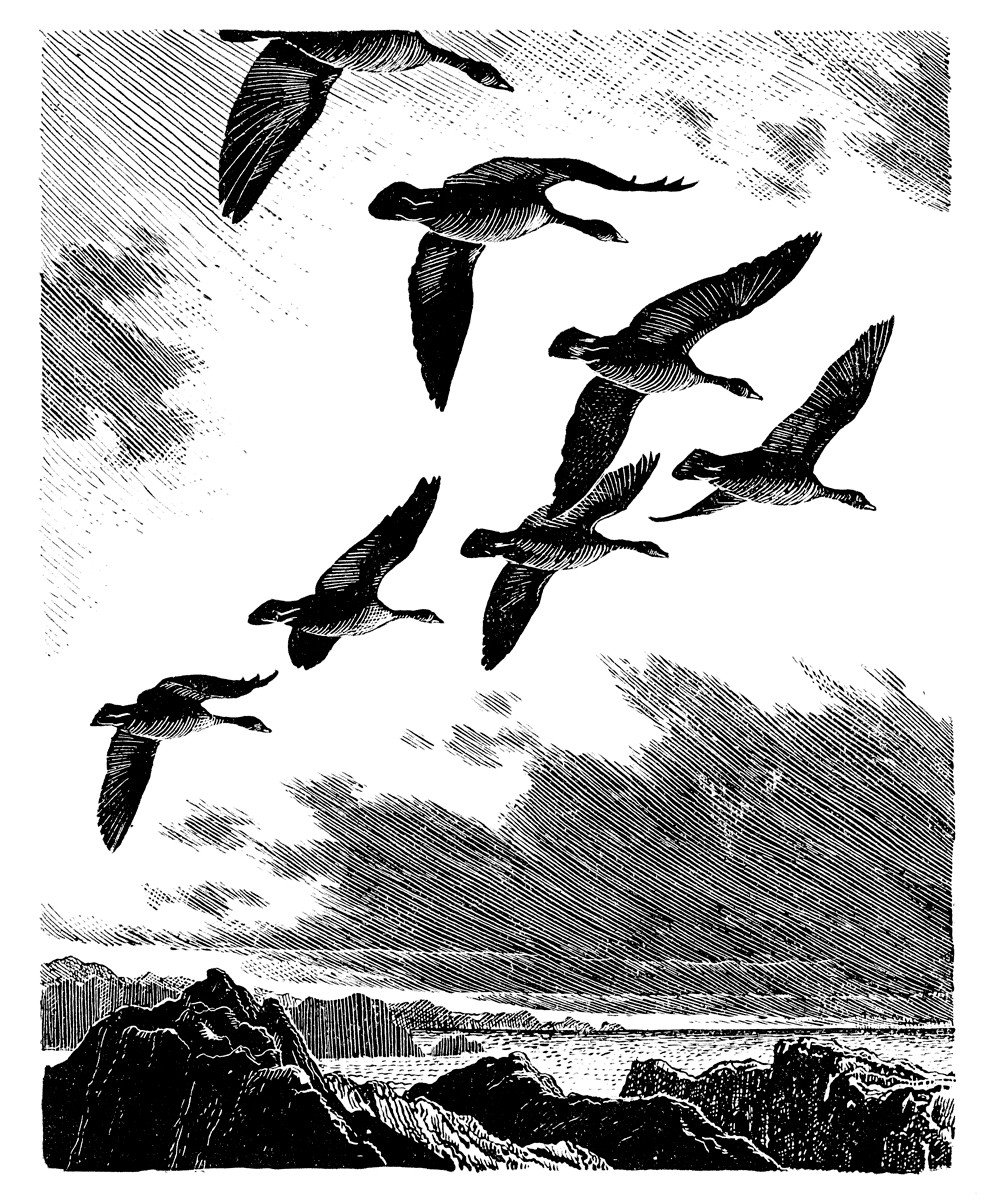

After the flare of the match, a few moments of silence. Then a glow, a flicker, a thin tongue of flame curling at the paper’s edge, sliding up a length of kindling, touching the bark, then slipping back into the little cave of orange light in the middle of the pile. It was my job to watch it didn’t go out, while he went to see to the cows. I crouched, and watched. There’s an essay in Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac (1949) that brought me back to that moment:It’s one of those times when a book transports you instantly into a memory: conjuring the feelings, the smells, the sounds of a brief, vivid moment of childhood. I was there again, with my grandfather, but this time feeling very much like the dog that Leopold describes: silent, expectant. A Sand County Almanac, and Sketches Here and There is a collection of Leopold’s writing from the 1930s and 1940s. Author, scientist, ecologist, forester, conservationist and environmentalist, Leopold was truly a powerhouse of natural history. His Sand County had a profound impact on the environmental movement, introducing the idea of wilderness management and environmental ethics. That makes it all sound rather dry, but in fact the essays sparkle with precise details. Whether he’s picking out the order of birdsong at dawn in a Wisconsin wood, following a mink track through the snow in January or tracing the first signs of thaw in spring, the essays are warm, beautiful things. They have some of the aphoristic appeal of Emerson, the wildness of Thoreau, the poetry of Whitman – but it’s the rhythm of them that gets you. Here he is in ‘March’, having heard the honk of geese overhead, ruminating on the role their migration plays in the world:My dog does not care where heat comes from, but he cares ardently that it come, and soon. Indeed he considers my ability to make it come as something magical, for when I rise in the cold black pre-dawn and kneel shivering by the hearth making a fire, he pushes himself blandly between me and the kindling splits I have laid on the ashes, and I must touch a match to them by poking it between his legs.

This is typical of Leopold’s style. His broad brushstrokes cover many thousands of miles to paint this grand pattern in nature, and then focus on a single detail – that wild poem, there to be enjoyed by anyone who knows how to stop and listen. These essays are absorbing stories – and they are useful too. We learn about the draba, a tiny flower that’s the first to bloom on the prairie, and about the sky dance of the woodcock in April and May; we learn about the owl at dawn who ‘in his trisyllabic commentary, plays down the story of the night’s murders’. And we learn to see things from every viewpoint (‘at this time every year I wish I were a musk rat, eye-deep in the marsh’, he says). So we see the woods as a dog sees them: a landscape of smells, full of rabbits. And we see them as a rabbit does, with a keen sense of the quickest line from meadow to woodpile hideout, for when the dog comes. Leopold teaches us how to read the stories in animal ecology, how to fit the tiniest momentary detail into a much bigger narrative of landscape and nature. This idea of the natural world as a book to be read runs throughout Leopold’s essays. In ‘February’, he ties together the chopping of wood with the making of history: ‘from each year the raker teeth pull little chips of fact, which accumulate in little piles, called sawdust by woodsmen and archives by historians’. The essay starts with Leopold looking at the fire he’s made with wood that he’s cut from an old oak on his farm. From there he traces time back from the log to the wood to the tree, and follows the saw as it cuts through eighty rings, slicing through eighty years of American history as it goes.By this international commerce of geese, the waste corn of Illinois is carried through the clouds to the Arctic tundras, there to combine with the waste sunlight of a nightless June to grow goslings for all the lands in between. And in this annual barter of food for light, and winter warmth for summer solitude, the whole continent receives as net profit a wild poem dropped from the murky skies upon the muds of March.

The words carry the rhythm of the saw, back and forth through the tree, through time. That rhythm carries through each repetition of ‘Rest! Cries the sawyer . . .’ – and the whole piece builds into a grand picture of the world as witnessed by the oak. In less skilled hands this might be a tortuous extension of a metaphor, but the strength and balance of Leopold’s prose are mesmerizing – much like watching the flames of a fire. Leopold is a master at seeing things differently. Whether he takes on the perspective of a goose or a mink or a muskrat, he creates these vivid worlds from the animals he has observed. But it is more than a clever prose style. One of his most famous pieces, ‘Thinking like a Mountain’, describes a moment when there is a deep shift in his thought. He kills a wolf, thinking that a land without wolves would be the deer hunter’s paradise. But as he watches the ‘fierce green fire die in her eyes’ he sees something new: that the wolf is integral to the life of the mountain, a keystone species on which the health of everything else depends. Having seen the devastation by deer of all wild country without wolves, he comes to think that ‘just as a deer herd lives in mortal fear of its wolves, so does a mountain live in mortal fear of its deer’. Projects to reintroduce wolves to places like Yellowstone National Park have shown what he meant, and led to the latest thinking on the possibilities of restoring land to its original state of wilderness. From their focus on the ecology of a single small farm in Wisconsin, the essays work towards an ethics of land: ‘The Upshot’. This final section of the book is Leopold’s concerted effort to set out a way in which we might negotiate the relationship of humans to land. All the work that Leopold does in the first two sections – demonstrating how to think like a beaver, a burr oak or a grebe – is now put to use in changing the role of Homo sapiens from one of conqueror of the land community to a fellow citizen and inhabitant of it. It’s a compelling case, even if it seems that what he really wants is impossible: he’d like there to be fewer people on the planet. Many scientists and ecologists and writers have built on the foundations that Leopold laid down in A Sand County Almanac, but that’s not the real reason the book has lasted. The secret of its appeal lies in the natural rhythms of life in its pages. To read these essays is to sit once again with a grandfather, to learn the lost wisdom of the woodsman, to appreciate the ancient warmth of a fire, to read the wealth of detail in a small patch of earth, and to follow your nose along a skunk track, carved by his smooth belly in the deep January snow.Now our saw bites into the 1920s, the Babbittian decade when everything grew bigger and better in heedlessness and arrogance – until 1929, when stock markets crumpled. If the oak heard them fall, its wood gives no sign . . . In March 1922, the ‘Big Sleet’ tore the neighboring elms limb from limb, but there is no sign of damage to our tree. What is a ton of ice, more or less, to a good oak?

Rest! Cries the chief sawyer, and we pause for breath.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 54 © Galen O’Hanlon 2017

About the contributor

Galen O’Hanlon thinks about his grandfather every time he lights a fire.