When my old English master died, I was lucky enough to have the first pick of his library. Most of the standard works of English Literature were there, including many beautiful old Oxford University Press editions, all bearing the signs of much use, and annotations in his instantly recognizable handwriting. Because JFM (as we called him) had taught me to love literature – I was young then, and how I wish I had listened more, and learned more! – I feel now, as I turn the pages that he once read, and look up quotations where he once searched, that he is teaching me still.

Like all enthusiastic readers, he had his favourites (Jane Austen, for example) as well as those whom he politely but firmly termed ‘overrated’, such as D. H. Lawrence. Among his books I found, as expected, no Lawrence, though I did come across (and instantly commandeered) the complete works of Graham Greene. He had never mentioned Greene: perhaps, as a strict Catholic, he thought him a touch too heretical for Catholic schoolboys.

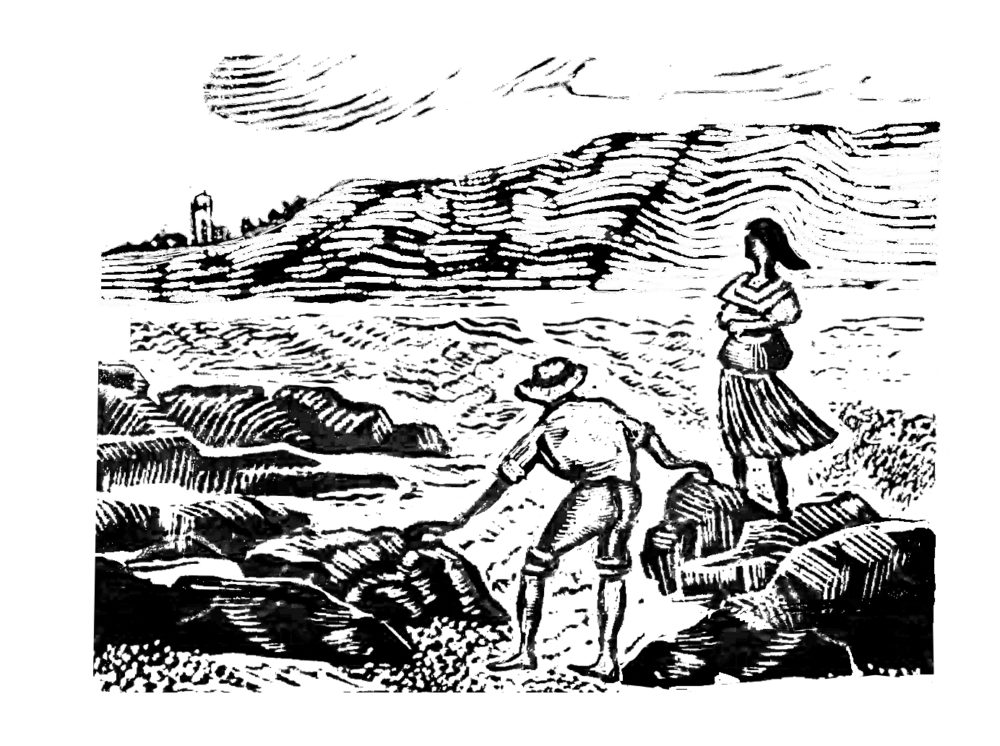

I took books that I knew would be useful, and so they have proved. And almost as an afterthought I took three old Faber paperbacks – L. P. Hartley’s Eustace and Hilda trilogy: The Shrimp and the Anemone, The Sixth Heaven and Eustace and Hilda. I was conscious that this was unfashionable literature, but thought the books might tell me more about JFM’s reading tastes. He had never mentioned them; perhaps they were another secret enthusiasm.

Naturally, I knew of L. P. Hartley; many of my contemporaries had had to ‘do’ The Go-Between for O level. I had read this later book – published in 1953 – and seen the film, but we never ‘did’ it in class, and I can now see why. JFM wanted us to think fo

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inWhen my old English master died, I was lucky enough to have the first pick of his library. Most of the standard works of English Literature were there, including many beautiful old Oxford University Press editions, all bearing the signs of much use, and annotations in his instantly recognizable handwriting. Because JFM (as we called him) had taught me to love literature – I was young then, and how I wish I had listened more, and learned more! – I feel now, as I turn the pages that he once read, and look up quotations where he once searched, that he is teaching me still.

Like all enthusiastic readers, he had his favourites (Jane Austen, for example) as well as those whom he politely but firmly termed ‘overrated’, such as D. H. Lawrence. Among his books I found, as expected, no Lawrence, though I did come across (and instantly commandeered) the complete works of Graham Greene. He had never mentioned Greene: perhaps, as a strict Catholic, he thought him a touch too heretical for Catholic schoolboys. I took books that I knew would be useful, and so they have proved. And almost as an afterthought I took three old Faber paperbacks – L. P. Hartley’s Eustace and Hilda trilogy: The Shrimp and the Anemone, The Sixth Heaven and Eustace and Hilda. I was conscious that this was unfashionable literature, but thought the books might tell me more about JFM’s reading tastes. He had never mentioned them; perhaps they were another secret enthusiasm. Naturally, I knew of L. P. Hartley; many of my contemporaries had had to ‘do’ The Go-Between for O level. I had read this later book – published in 1953 – and seen the film, but we never ‘did’ it in class, and I can now see why. JFM wanted us to think for ourselves. The Go-Between is not dull, but it is formulaic, heavy with symbols, inviting stock responses. JFM did not believe in ‘set answers’ or in rote learning. So I wondered why this trilogy was on his shelves. It’s a question I’ve only recently answered. For a decade and a half I’ve been carrying the paperbacks with me from house to house, but only now have I got round to reading them. The trilogy’s central characters are a pair of siblings, Eustace and Hilda. The story spans the First World War, beginning with Eustace as a little boy and ending with him in early manhood. The children’s mother is dead, and by the opening of the second volume, so is their father. Eustace is the novels’ centre of consciousness; Hilda, who is four years older, is seen through his eyes; his vision is what the novels are about. As you might expect from a skilled writer, Eustace’s vision is flawed: the reader often sees more than he does. When the trilogy opens the pair are living in Norfolk, at the seaside, members of the straitened middle class. The household keeps no carriage, and Eustace is not destined to go to a public school; there is a servant, but the house is small. Family life is claustrophobic, presided over by a maiden aunt. Then things change. An old lady in a bath chair, whom Eustace at first sees as an ogress, takes an interest in him; Hilda insists he go to tea with this Miss Fothergill; the two become friends and play piquet together. When Miss Fothergill dies she leaves Eustace £18,000. This means he can now become a gentleman; his father accepts the legacy, against the advice of the aunt. Around this time Eustace falls ill during a paperchase and is taken to Anchorstone Hall, the local great house, where he meets Dick Stavely, 15 years old, handsome, kind, charming and aristocratic. Eustace likes Dick, but Dick is attracted to Hilda, and much as Eustace dreams of being invited back to the Hall, it is Hilda, not Eustace, Dick wants to see, though Hilda is not at all interested. However, now that Eustace has money, he is surely closer to Dick’s social milieu. And so it proves in the second volume, when Eustace, now an undergraduate, makes it to the Hall, along with his sister, who has become a rather severe bluestocking. He has shared his inheritance with her, and she is using it for charitable purposes. Dick pursues Hilda without apparent success and, perhaps unwittingly, charms Eustace. Eustace is using Hilda to secure his position with Dick, and the Stavely family are not pleased at the prospect of Dick marrying a middle-class girl. At this point Dick’s aunt, Lady Nelly, invites Eustace to her Venetian palazzo for the summer in order, we later discover, to remove him so that the family can effectively scotch Dick’s relationship with Hilda. The third volume is set in Venice, with Hilda and Dick’s romance off-stage in England. I won’t reveal what happens, but only say that the triangular relationship and the manipulations are handled with great subtlety. The importance of money, and the fact that love is not quite all it seems, are reminiscent of Henry James. Eustace is an innocent caught in the toils. So is Hilda, though she is less innocent, more knowing, though what she knows we do not ever quite discover. Hartley is at home with these Jamesian themes, and he has a lightness of touch that the Master often lacks. Two forces are at work here and throughout the trilogy, both beloved of the English novelist: sex and snobbery. Eustace is a social climber, though a naïve one, and his legacy enables him to rise; but it is not really enough to enable him to rise definitively. He doesn’t enjoy the unquestioned status of, say, the heiress Isabel Archer in The Portrait of a Lady. Eustace’s legacy is enough to give him a taste for the high life without giving him the means to satisfy that taste completely. So, staying in the Venetian palazzo with Lady Nelly, he is an outsider, an oddity, though he seems unaware of it. Eustace is also sexually naïve. There is no hint that he finds Dick sexually attractive, though it is hinted that Dick might be interested in him (after all Dick was at Harrow, and might well be au fait with homosexuality in a way middle-class Eustace is not). But Eustace is more than simply virginal; he seems asexual; in Venice a childhood friend, now a rather racy divorcée, tries to pick him up, and he comically misreads the signals. Sex means nothing to him; he seems unaware of the almost absurdly flirtatious gondoliers Lady Nelly employs, or the significance of her Italian lover. All this, perhaps, points to something greater: he is a spectator at the game of life, an onlooker, not a participant. Hilda is less keen to succeed socially than her brother, but as a woman she has to fend off male sexual advances, which she does with disastrous ineptitude. The siblings have a younger sister who is married at 18, and who says of Hilda: ‘She doesn’t understand men, and has never tried to.’ Why Hilda should be so frigid is never explained. There is no hint that she is attracted to her own sex, but it is clear that she fears and loathes men. Despite her beauty and intelligence, she remains a social misfit. The aunt has this to say: ‘No good ever comes of trying to climb out of the class of society into which you are born . . . Eustace always had a hankering after rich people, and it will be his undoing, just as he has made it Hilda’s. He goes about with them, but he does not understand their way of looking at things, nor did Hilda.’ In the end it may be better to stay in one’s own familiar milieu, dull as that may be, than to try and break out of confinement. Freedom can be terrifying. The Eustace and Hilda trilogy is a comedy of manners, an illustration of how the middle classes are lost in the upper-class world of great houses and Venetian palazzi, and puzzled by men called Dick who do not share their bourgeois morality. But like all good comedy, it has an underlying seriousness. The world Eustace finds himself in is mysterious to him; for his sister, who is more perspicacious, it is frightening. And how true this still rings, several decades later: some of us find life socially awkward, or are not quite at ease in our own skins sexually – or both. A reissue twelve years ago by the New York Review of Books described the trilogy as ‘a comedy of upper-class manners; a study in the subtlest nuances of feeling; a poignant reckoning with the ironies of character and fate . . . about the ties that bind’. Yes, but it is more than that: it becomes darker as it progresses, darkest of all in the sunlit Venetian scenes, though this darkness is always subtle. The NYRB edition also quotes Betjeman’s judgement: ‘The combined effect of these three books is one of mounting excellence. Eustace, the central figure, is an immortal portrayal of the delights and agonies of childhood and adolescence.’ The truth is that Eustace never grows up, and it is in this that the trilogy’s greatness lies: it is a simple and beguiling story, but under its polished surface lurk truths that perhaps we would rather not face.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 44 © Alexander Lucie-Smith 2014

About the contributor

Alexander Lucie-Smith is a Catholic priest who writes on cultural matters.