From about the thirteenth to the sixteenth century, anyone who could afford it owned a ‘book of hours’ and kept it close at hand for daily use. It contained the prayers of the divine offices to be said at appointed hours, as well as psalms, lists of saints and a calendar, often tailored to the particular place in which it was used. My diary, the only book I use many times a day, is a paltry thing beside these medieval books, some of which are made visually beautiful with illuminations, and all of which are conceptually beautiful in their weaving of the hours of each day with the arc of the whole year.

Katherine Swift worked as a librarian of manuscripts and rare books until 1988, when she moved to Shropshire to make a garden. After twenty years at the Dower House in the grounds of Morville Hall, and drawing on a lifetime’s work with both manuscripts and plants, she published her own book of hours. There are no prayers in it, but here, still, are the hours of the day and the cycle of the seasons. We make our way from the silence of a December midnight (Vigils: the hour of darkness and waiting) to the high sun and roses of Sext. This is June, all life and busyness. Then on towards the last of the canonical hours, Compline, with its tonal character of completion, retrospect and thanks. I think The Morville Hours (2008) is quite as lasting as its forbears. There’s an intricate calendar mapped out here which is not to be found in the pages of my diary.

I knew a bit about Katherine Swift before her book was published because I’d read her gardening columns in the weekend papers almost as religious observance. The gardening section was always the last unclaimed scrap on the communal Sunday breakfast table when I was a student, but that was the one I was after. Perhaps students now have allotments or grow their own in window

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inFrom about the thirteenth to the sixteenth century, anyone who could afford it owned a ‘book of hours’ and kept it close at hand for daily use. It contained the prayers of the divine offices to be said at appointed hours, as well as psalms, lists of saints and a calendar, often tailored to the particular place in which it was used. My diary, the only book I use many times a day, is a paltry thing beside these medieval books, some of which are made visually beautiful with illuminations, and all of which are conceptually beautiful in their weaving of the hours of each day with the arc of the whole year.

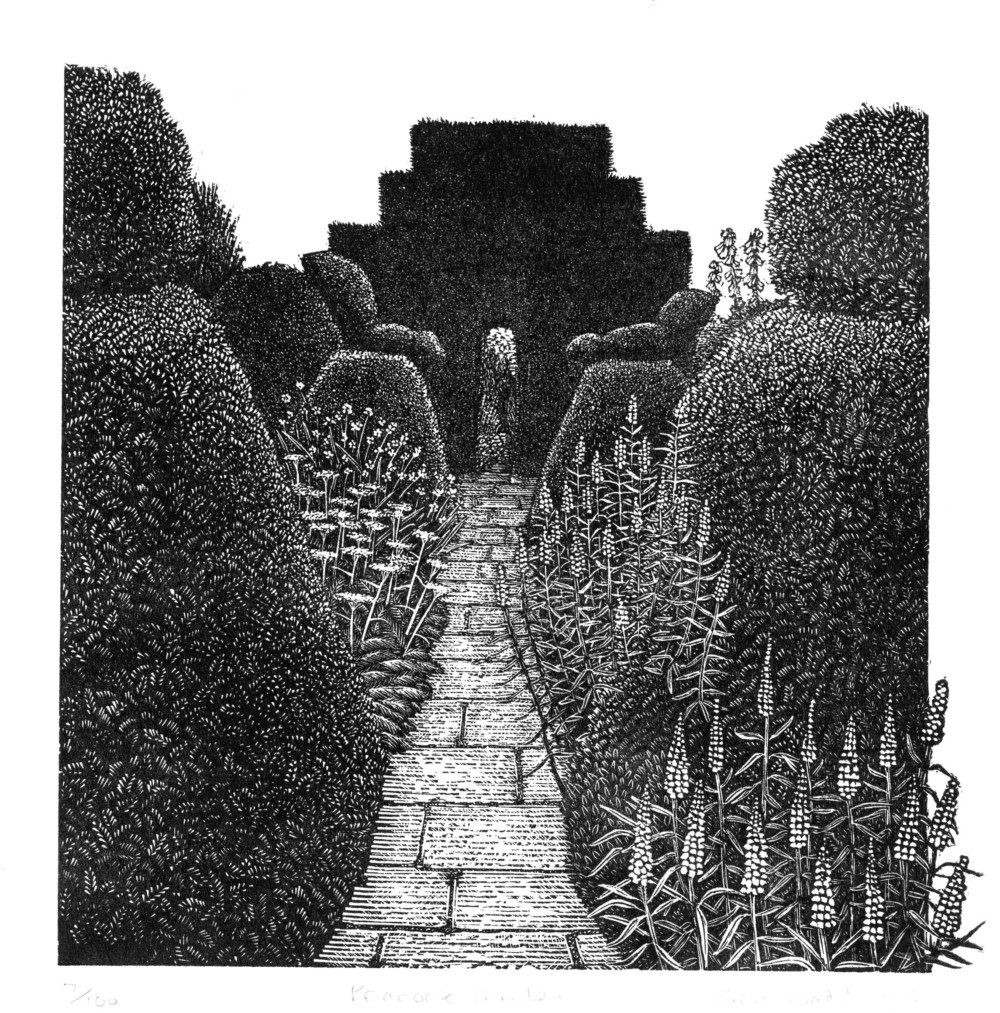

Katherine Swift worked as a librarian of manuscripts and rare books until 1988, when she moved to Shropshire to make a garden. After twenty years at the Dower House in the grounds of Morville Hall, and drawing on a lifetime’s work with both manuscripts and plants, she published her own book of hours. There are no prayers in it, but here, still, are the hours of the day and the cycle of the seasons. We make our way from the silence of a December midnight (Vigils: the hour of darkness and waiting) to the high sun and roses of Sext. This is June, all life and busyness. Then on towards the last of the canonical hours, Compline, with its tonal character of completion, retrospect and thanks. I think The Morville Hours (2008) is quite as lasting as its forbears. There’s an intricate calendar mapped out here which is not to be found in the pages of my diary. I knew a bit about Katherine Swift before her book was published because I’d read her gardening columns in the weekend papers almost as religious observance. The gardening section was always the last unclaimed scrap on the communal Sunday breakfast table when I was a student, but that was the one I was after. Perhaps students now have allotments or grow their own in window boxes, but there wasn’t much gardening at Oxford fifteen years ago. I wasn’t even sure about doing any digging myself. But I wanted, passionately, to look at gardens and to read about them. This was what I did on Sunday mornings. I was aware (and still am) of turning to gardens, and garden writing, for a kind of replacement liturgy. Swift’s columns often had a ceremonial feel, though they were practical too, and rich in botanical knowledge. I liked that combination. She might be writing about the order in which plums and damsons flower, or about the coming of the first frost – a critical moment for gardeners, a great hinge in the turning year, and just the sort of thing I’d never noticed. One December Sunday she told a story about having two thousand tulip bulbs carefully laid out for planting when suddenly time caught up with her and a freezing night came on. She worked through the evening by torchlight and got them all planted as the grass froze around her and a shooting star sprang through the clear cold air. I still remember the effects of that column. I worked late at my desk with a maniacal energy which came, I think, from some sudden sense of connection between labour and pleasure, now and later, the pencilled timetable on my wall and the perpetual calendar of the years. Swift loves the intricate connectedness of things in books of hours, and achieves that intricacy in the structure of her own book, where each chapter takes its subjects and moods from an hour, and a time of year, and a period of history. It is all interwoven as tightly as a knot garden (yes, of course Swift has made knot gardens), and yet it feels responsive to anything that may happen. That’s one of the beauties of a tight structure: because the framework is solid and wins our trust, all sorts of wild things can happen within its limits. Think of Ulysses! The cunningly ordered scheme of it gives licence for all Joycean anarchy. (The comparison is not entirely arbitrary since Joyce’s novel is a book of hours, and has, to my mind, more in common with the medieval calendars than with the Homeric epic from which it ostensibly takes its form.) Swift knows about containment and spillage. It’s the basic dynamic of her garden. In summer the plants billow out over the clipped box hedges that mark the borders, and roses ramble profusely away from their arbours. In winter, with the disappearance of summer’s temporary improvisations, the straight lines of the garden are revealed, dark evergreen and brown. Moving through the sequence of the months in the garden at Morville, we also move through the long history of the place. So in the chapter on ‘Prime’, we are at 6 o’clock in the morning (the first of the daytime hours) in March, and Swift also pieces together clues to the lives of the Normans in Shropshire in the twelfth century. There is the arcade of semi-circular arches in the local church, and the question of where the building stone, tufa, came from. Very nearby it seems: there is an outcrop of tufa-bearing limestone on the escarpment rising just across from the Mor Brook. March is the month for digging. The forward movement through the hours and the centuries becomes also an archaeological digging back; sometimes the past comes to the surface unlooked-for in the form of scraps turned up in a border, slivers of medieval glass, willow-pattern china or ‘broken clay pipes in the flower-beds, their airholes stopped with soil’. Who broke that plate or that pipe here, in this place? ‘Did they stand as I stand now,’ Swift asks, ‘watching the clouds on the hillside?’ She tells some of their history in her book, and she makes some of their history in her garden. Her planting and pruning take on a narrative quality. She grows a yew cloister in honour of the monks of the Benedictine priory which stood on this ground until the Reformation, and she makes a seventeenth-century garden filled with the favourite plants of those who lived and died here during the Civil War, when the nearest town, Bridgnorth, was besieged and the heir of Morville died in battle at Edgehill. Swift is mostly alone as she gardens, and she writes about her natural tendency to isolation, but she weaves or grafts herself into centuries of company. In many of the medieval almanacs – for instance in the popular Kalendar and Compost of Shepherds – the hours of the day and the months of the year are mapped on to the stages of human life. There are varying opinions about how the cycles correlate, so that birth comes sometimes with the zero hour of deep winter, and sometimes with the dawn of spring, all bud and imminent bloom, but always we pass through June, noon, high sun and the start of maturity, and on into the harvest, the evening, the autumnal reaping of what was sown before. For those who carried these associations deep in mind, the hours were a life in miniature, and to mark the hours was a way of telling one’s life. There are only short passages of memoir and family history in The Morville Hours, which is as it should be since personal experience is a small part of a scheme which encompasses the life of the land, the community, the church, the plants. But there is a powerful sense of Swift measuring the shape of her life against the shapes delineated in the books of hours. It is a kind of offering-up, both in the sense of offering up a picture to see how it fits, and in the sense of making an offering – giving one life to the larger story. Not that a real life can be fitted easily to any pre-worked pattern, of course, and that difficulty is part of the point. Swift writes of messy displacements, numerous house moves, the troubling lack of pattern. She finds, movingly, ways to link the blazing tempers of her parents with the blaze and ruin of high summer in the garden. The hours seem roomier than I had understood: more accommodating of erratic lives. There is room in the ‘De Profundis’ for the long blanknesses of depression. Between that and the joyous ‘Te Deum’, one feels that most experiences might find a place. My own garden is in need of investment. I haven’t given it the time. There are huge gaps which could have been filled had I taken a mere day in the autumn to divide the perennials; envelopes of seeds sit indoors unsown (the yellow aquilegias I liked in a friend’s garden, a Spanish broom sent by a botanist). I garden enough to know precisely the look and feel of Swift’s ‘hollow-stemmed galega, all knees and elbows’ collapsing along with the dying show of middle summer, but it feels almost fraudulent to read so many gardening books and to do so little of the practical work myself. I hope there’ll be a season of my life during which it feels imperative to plant and propagate, however incompetently. I want to be able to read a tree or tell the date of a hedge by looking at it. But that kind of knowledge comes from holding a pruning saw rather than a book in hand. In the meantime, perhaps it’s not so strange to garden vicariously through reading. Swift, after all, writes as much about the life of books as plants. I tried to read The Morville Hours on a train once and couldn’t do it. I thought that under the fluorescent light of the noisy Quiet Carriage, with a packet of Quavers from the platform vending machine, I could think myself into stillness. It didn’t work, and in truth reading rarely works for me as antidote. It’s most powerful, I find, in expanding the compass of a moment in which a book and the circumstances of reading are somehow in sympathy. So if I notice the colour of rowan berries on the way to the office, or if there’s a pause in the evening when the fire is lit, or if I remember that it’s Candlemas, or the winter solstice, I’m deeply glad to read a chapter of The Morville Hours. For as long as I read, and sometimes long after, I have a sense of where I am.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 50 © Alexandra Harris 2016

About the contributor

Alexandra Harris is the author of Romantic Moderns and Weatherland. She is Professor of English at the University of Liverpool and likes to watch the seasons turn there, as well as in Oxford and West Sussex.