There are two footpaths in the Lake District that join the village of Patterdale to the long ridge above it called St Sunday Crag. One of these is marked very prominently on the Ordnance Survey ‘Explorer’ map of the north-eastern lakes: it runs up past Thornhow End and through the scattered boulders of Harrison Crag, and on up to the smaller summit of Birks. From there it’s a pleasant stroll along the ridge to St Sunday Crag proper, then across Deepdale Hause, looking down into Deepdale Beck, and on to the heights of Fairfield.

I’m looking at the map as I write this, and I can’t help stealing glances at the bold green paths which radiate temptingly out across those closely packed orange contours. I peer down at Hart Crag and Great Rigg, both short but exhilarating skirts across the summit from Fairfield, and then up to Helvellyn and Stybarrow Dodd, and to Caudale Moor and the High Street Range just across the valley. And as I look at them and the paths between them, or gaze at those magical letters ‘PH’, which indicate that villages along the way might well be worth a stop-off, I remember the days I’ve spent on the fells, alone or with friends, and think of the trips yet to come.

There’s a second path up to St Sunday Crag from Patterdale which isn’t quite so well marked. It starts off like the first, but just as the dotted green line on the Ordnance Survey stomps purposefully up to the summit of Birks, a second track skirts along to the right, following the contours on the northern side of the St Sunday ridge, through a grassy landscape of boulders, until it finally joins its cousin at the top.

This path is little more than a faint grey dotted line on the published walkers’ maps but is the clearer of the two on the ground. On a fine day, as it was when I was first up in that neighbourhood, navigation is never much of a problem on a proud fell like St Sunday, and so I followed the path more travelled (it seemed) with little worry that I would get lost. After about half an hour’s climb out of Patterdale, when the gradual settling of a hastily consumed full English breakfast was starting to slow the proud pace of the early morning, I turned, sat and surveyed where I’d come from. Ullswater lay immediately before me, Fairfield behind. To my right was the top of Birks, and to my left the great peaks of the Helvellyn chain that divide the whole Lake District in two. Even as I regretted that third rasher of bacon, I knew t

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inThere are two footpaths in the Lake District that join the village of Patterdale to the long ridge above it called St Sunday Crag. One of these is marked very prominently on the Ordnance Survey ‘Explorer’ map of the north-eastern lakes: it runs up past Thornhow End and through the scattered boulders of Harrison Crag, and on up to the smaller summit of Birks. From there it’s a pleasant stroll along the ridge to St Sunday Crag proper, then across Deepdale Hause, looking down into Deepdale Beck, and on to the heights of Fairfield.

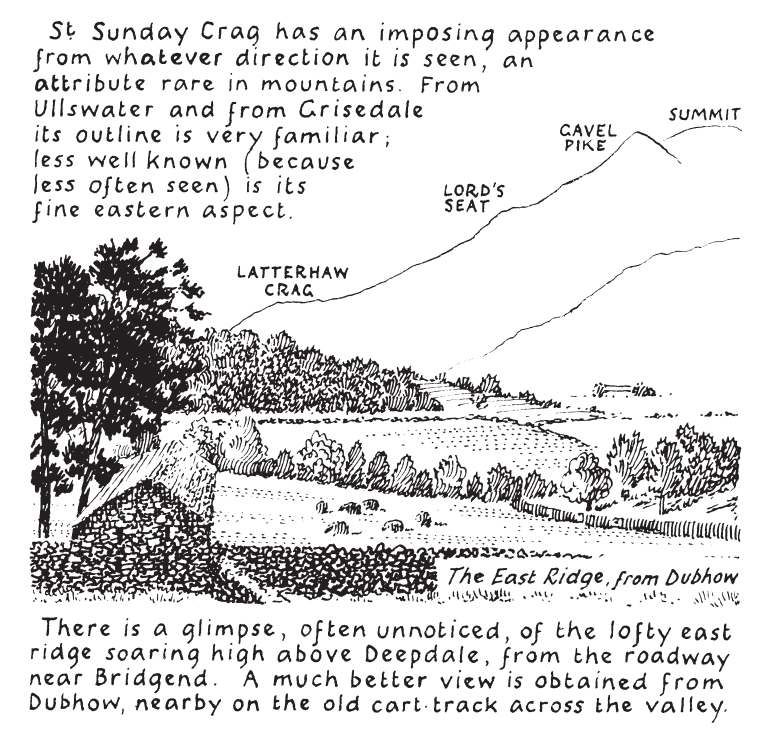

I’m looking at the map as I write this, and I can’t help stealing glances at the bold green paths which radiate temptingly out across those closely packed orange contours. I peer down at Hart Crag and Great Rigg, both short but exhilarating skirts across the summit from Fairfield, and then up to Helvellyn and Stybarrow Dodd, and to Caudale Moor and the High Street Range just across the valley. And as I look at them and the paths between them, or gaze at those magical letters ‘PH’, which indicate that villages along the way might well be worth a stop-off, I remember the days I’ve spent on the fells, alone or with friends, and think of the trips yet to come. There’s a second path up to St Sunday Crag from Patterdale which isn’t quite so well marked. It starts off like the first, but just as the dotted green line on the Ordnance Survey stomps purposefully up to the summit of Birks, a second track skirts along to the right, following the contours on the northern side of the St Sunday ridge, through a grassy landscape of boulders, until it finally joins its cousin at the top. This path is little more than a faint grey dotted line on the published walkers’ maps but is the clearer of the two on the ground. On a fine day, as it was when I was first up in that neighbourhood, navigation is never much of a problem on a proud fell like St Sunday, and so I followed the path more travelled (it seemed) with little worry that I would get lost. After about half an hour’s climb out of Patterdale, when the gradual settling of a hastily consumed full English breakfast was starting to slow the proud pace of the early morning, I turned, sat and surveyed where I’d come from. Ullswater lay immediately before me, Fairfield behind. To my right was the top of Birks, and to my left the great peaks of the Helvellyn chain that divide the whole Lake District in two. Even as I regretted that third rasher of bacon, I knew that there was nowhere else in the world I would rather have been than sitting on that unmarked rock. Few people knew or understood this feeling better than Alfred Wainwright – a self-deprecating Lancastrian who walked, sketched and extolled the fells in seven beautifully idiosyncratic (and simply beautiful) books collectively called A Pictorial Guide to the Lakeland Fells. Long drawn to the region from his home in Blackburn, Wainwright systematically set about his paean to the glories of the fells in the autumn of 1952. His panegyric, he decided, would divide Lakeland into seven regions; each would have a book of its own, each of which would be written in two years. For thirteen years (or rather twelve years and fifty-one weeks – he proudly announced that he finished the sequence a week early), Wainwright charted the district fell by fell, summit by summit and view by view. The books are little masterpieces. In each, the fells appear alphabetically, described from a geological perspective, and from every possible angle of ascent (and descent). Summits are praised or denigrated, and all – even the least prepossessing – are sumptuously illustrated. Famously, each of the books is set in a facsimile of Wainwright’s own crabbed and painstaking hand, with the result that the reader feels he is peering into the geological billets-doux of one of the great English eccentrics – a sense of intimacy only partially dispelled by the knowledge that they have now run to multiple impressions and have never fallen out of print. Every reader of Wainwright will have his or her favourite passages: if nothing else the sequence is a monument to the self-effacing whimsy of a modest man. Enthusiasts point to the dedications of the different volumes, for example – The Eastern Fells ‘to the men of the Ordnance Survey’, The Southern Fells ‘to the sheep of Lakeland’, The North Western Fells ‘to those unlovely twins, my right leg and my left leg. Staunch supporters which have carried me about for over half a century, endured without complaint. And never once let me down.’ Again and again, the lovingly pastoral tone is enlivened by a wry (and occasionally macabre) humour. Of Hopegill Head, for example (in The North Western Fells):The crag is a haven of quiet solitude; within sight, but out of reach is a popular walking route. In summer sunlight there is pleasant colour, the bilberry – greenest of greens – making a luxuriant velvety patchwork among the grey and silver rocks. In shadow, the scene is sombre and forbidding. The silence is interrupted only by the croaking of the resident ravens and the occasional thud of the falling botanist. This is a place to look at and leave alone.But the books are more than a collection of idyllic sketches and dry witticisms. They are an intensely personal account of a landscape that Wainwright loved, and one that he makes exceptionally welcoming to the reader. I had a copy of The Eastern Fells with me that day on St Sunday Crag, and it was Wainwright’s description of the fell, quite as much as the captivating concentration of contour-lines on the Ordnance Survey map, which had determined my route:

Every walker who aspires to high places and looks up at the remote summit of St Sunday Crag will experience an urge to go forth and to climb up it, for its challenge is very strong. Its rewards are equally generous, and altogether this is a noble fell. Saint Sunday must surely look down on his memorial with a proud satisfaction.But somehow one detail of Wainwright’s description had passed me by that morning, and it was only when reviewing my triumphs in an Ambleside pub in the evening that I noticed it. There, on p.8 of the description of St Sunday Crag, is Wainwright’s own inked view from the very spot where I had been sitting. His foreground is dominated by an unnamed woman – mine, alas, had been empty – but otherwise the view was the same, from the boulders on the hill down to Ullswater beyond. The coincidence wasn’t an especially surprising one, I realize. There are hundreds of such views in the seven-book sequence on the Lakes, and I’ve probably shared several dozen of them at one time or another, but for some reason I keep coming back to that episode in my head. Clearly the Lakes encourage reflection. Wainwright understood this too, of course. Each of his books closes with a moving passage, which ponders on the walks, the sketches and the writing of the previous two years, and bids farewell to one stretch of the Lakes, while stealing a glance forward to the treats still to come. By the last book, this melancholy is at its sumptuous best, and his famous conclusion provides an electrifying valediction to the great project, and to the spirit which inspired it:

The fleeting hour of life of those who love the hills is quickly spent, but the hills are eternal. Always there will be the lonely ridge, the dancing beck, the silent forest; always there will be the exhilaration of the summits. These are for the seeking, and those who seek and find while there is yet time will be blessed both in mind and body. I wish you all many happy days on the fells in the years ahead. There will be fair winds and foul, days of sun and days of rain. But enjoy them all.Time was precious to Wainwright, not because he was 58 when he completed The Western Fells – for all his protestations about the fading of the light, he was still to write his companion to the Pennine Way, to devise the ever-popular coast-to-coast walk, and to broaden further his vision of the Lakes through television and coffee-table books – but rather because he was well aware of the demands of the workaday world. Wainwright’s first experiences of the hills had to be stolen from a working life in Blackburn: his was a delight in the fells which continued even after the train, boarded in Windermere or Oxenholme or Penrith, had taken him home. He talks repeatedly in his books of the memories stored up on the hills for delectation when winter winds or mundane responsibilities kept the walker from his spiritual home, and of the delights to be gained from poring over the maps of Bartholomew or the Ordnance Survey, dreaming of being there again. And this, I think, is where the greatest appeal of the Lakeland sequence lies. While each of my copies has been battered by wind as I leafed through them on various summits, their dust-jackets torn by hasty stuffing into a pocket during a squall of rain, they really come into their own in a pub or in an armchair (or best yet in a pub armchair). The laboriously printed descriptions of paths and stiles, of ridges and waterfalls, provide marvellous inspiration for an adventure tomorrow but are still better as a prompt for happy memories of yesterday.Wainwright’s seven tightly packed little volumes aren’t guidebooks, they’re little capsules which bring the Lakes back to life in the minds of everyone who has been there, and who reads them. Wainwright is often criticized by a certain type of walker for overpopularizing the Lakes, but I’m not so sure that he did – at least not through his books. The Pictorial Guides are so fabulously popular not because they introduce people to a world they don’t know, but because they so beautifully shape our memories of a landscape that we do know. When I think of St Sunday Crag now, I see it through Alfred Wainwright’s eyes, as well as my own. And that is just the way I like it.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 30 © Andy Merrills 2011

About the contributor

Andy Merrills teaches ancient history at the University of Leicester. He has written extensively on the history and archaeology of North Africa, but he escapes to the fells whenever he can.