11 November

Waiting for the bus to Saratoga Springs, a Black mama squashed down her suitcase with her big butt, thighs splayed.

‘Where d’yall get them boots?’ she demanded. ‘Ah’d like a pair a boots like that.’

‘I got them in England,’ I replied, prissily.

‘Y’all from England then?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well! You speak real good English for someone from England.’

Her man explained about France and French, Germany and German, but she was having none of it.

My journey got weirder. From the bus station I took a rattly old cab with a rattly old lady driver, greasy hair, pasty skin, who announced: ‘I’ll be having a bucket on that passenger seat for the next seven months.’

‘Why d’you need a bucket?’ I asked.

‘To catch the vomit. Driving this car all winter long’ll make me nauseous. That’s because I’m pregnant.’

‘Congratulations!’ I couldn’t hide my surprise. She looked about 60.

‘Yeah, my youngest son, he’s 24, and I haven’t told him yet. I lost the last baby in March, had a real messy miscarriage. My boyfriend, he’s real happy ’bout it, but I’m not so sure.’

I didn’t need to hear more but couldn’t resist asking why.

‘Hell, I got eight grandkids! Youngest’s just a year old. Know what though, when I had the gastric band put in they said it’d play havoc with my hormones, I wouldn’t need contraception. Now look what happened.’

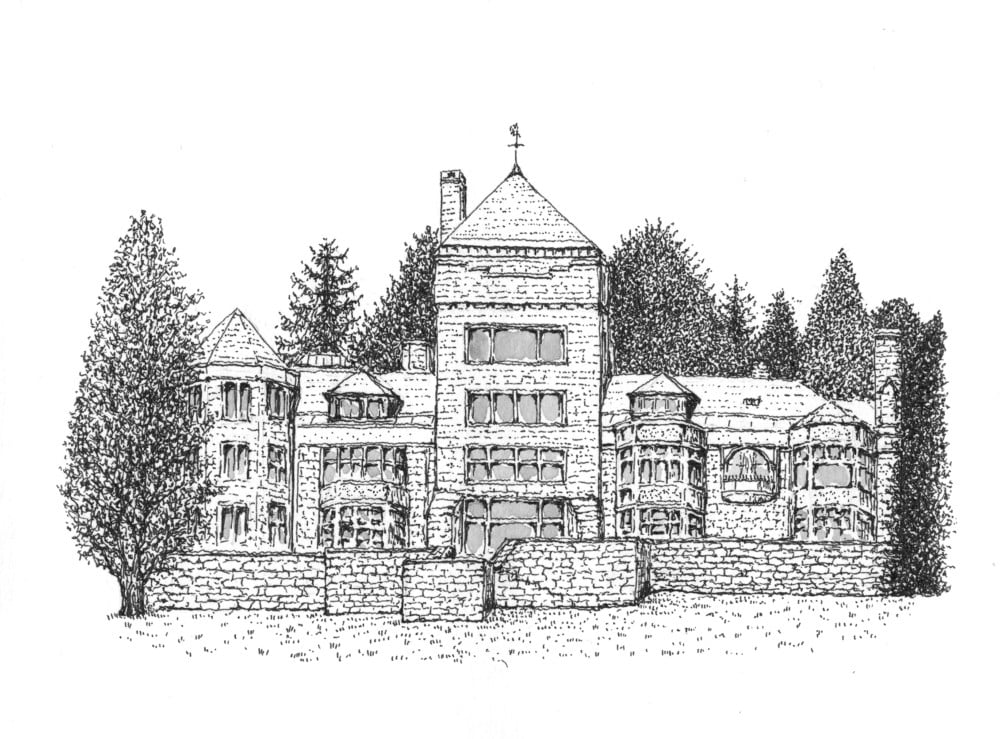

I was digesting this, as it were, when we entered a different world. Through imposing stone gates, up a private forested drive, over a lake, glimpsing a once-famous rose garden. A break in the autumn foliage revealed neo-Tudor turrets and a hefty portico, supposedly modelled on Derbyshire’s Haddon Hall. In this mansion and in cabins and cottages dotted throughout the grounds an LA playwright completed a scene, husband-and-wife installation artists prepared for their show in Paris, a painter dabbed at a canvas then wiped it off, a novelist emailed his husband in Berlin, and a composer rose from her Steinway to perform some yogic stretches.

I had arrived at Yaddo and was relishing the prospect of a month with nothing to do but write. My benefactors were the poetess Katrina Trask and her wealthy industrialist husband Spencer who, following the tragic deaths of their children in the 1880s, had decided to leave their mansion not to some distant cousin who didn’t give a damn, but as a haven for artists and intellectuals in need of a retreat. My lovely rooms were once Sylvia Plath’s, with a bathroom big enough to host a party in ‒ I wouldn’t be the first, the Director assured me. Other guests had included Truman Capote, Philip Guston, Aaron Copland, Ted Hughes and Leonard Bernstein; John Cheever virtually lived here, and was behind the building of the swimming pool. Good company, I hoped, alive and dead.

Later

Slightly nervous about dinner, not knowing the protocol or what to wear. The dining-room is panelled in black wood and the chairs resemble medieval thrones, so deep they shrink you to child size. This childlike state is reinforced by the way we don’t have to do anything for ourselves. No DIY, no bills, meals provided, including a packed lunch. Even our social lives are organized: every evening is an entertaining dinner party, but for which we haven’t had to invite guests, plan menus, shop, cook or clear up afterwards. I’m told the mansion is haunted, and th

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inWhat a perfect basis for a novel: hole up some highly charged ‘creatives’ in a secluded location and propel them from Eden into a Sartrean existentialist hell. Published in 1969, Real People is a subversively mocking but also poignant coming-of-middle-age comedy. Janet Smith (she adds ‘Belle’ to make herself seem elegant) is a priggish ‘lady writer’ who converses on highbrow matters over dinner. She and her fellow artists smugly agree that here at ‘Illyria’ they blossom into Real People ‒ their real best selves as they would be in a decent world, away from the stress of daily life. Janet is thankful to see the back of unreal people, particularly her boring insurance executive husband and tiresome children. But all is not as wonderful as it seems. Janet’s stories turn out trivial and pretentious. She’s discouraged. Other artists are blocked in various ways, or find they are past their prime. But still, it’s paradise. When not working they swim and play croquet. Then into this kingdom intrudes Anna May Mundy, a beautiful flirtatious minx, who breaks the spell, wreaks havoc and triggers a funny and painful denouement which teaches Janet something about herself. She had boasted about not being avant-garde or needing to create imaginary worlds like a historical novelist or Kafka, and of finding material simply by observing her own life, but like Jane Austen’s Emma she has closed her eyes to herself and what’s happening under her own nose, and it takes this crisis to open them. Lurie wittily exposes the difficulty of clearly seeing both ourselves and others ‒ seeing the real person. Sexy Anna May Mundy ‒ a catalyst like Emma’s Harriet Smith ‒ is subject to distorted interpretations by Illyria’s residents. Pop artist Nick makes her into ‘American Girl with Coke No. 3’, her hair lemon-yellow plastic; landscape painter Kenneth renders her a sylvan nymph; critic Leonard Zimmern considers her an anti-Semite; while Janet speculates that she’s Estella, forced by the scary Director, the Miss Havisham figure, to wreak revenge for her own broken heart. Perhaps there is no such thing as ‘real’ people, Lurie suggests; we are what others make of us, and eventually we are all ghosts. But the best thing about Real People is the wince-making accuracy with which Lurie pinpoints the self-doubts, affectations and egotism of writers, and specifically ‘lady writers’. While confiding in her diary, our heroine can’t help trying out writerly dialogue and similes. ‘Down below the rose garden I can hear cars whirring past on the thruway, or/like gusts of wind. Gusts of wind like cars whirring past? (SAVE THIS).’ In the book I was writing I had just used exactly that image, which of course now had to go. Even in extremis Janet self-consciously shapes life into prose and adds to her store of usable anecdotes. Yet Janet is disingenuous because a ghost story she has just dreamed up is clearly absurd, while what is happening around her ‒ what she isn’t writing about ‒ is far more pertinent. She can’t write about that because if she writes about ‘real’ people they will be hurt or shocked. She censors herself, and the result is these pointless fables. What should she do? Write about what matters to her ‒ her family, her husband’s colleagues, fellow guests ‒ and risk exile to social Antarctica, or give up altogether? Almost as dire, Janet knows that if she writes about Illyria she risks never being invited back. It’s just not the done thing; it would destroy the mystique. She wonders why she can’t recognize and experience things, then choose not to write about them. She concludes that it’s because it is disagreeable to have large areas of life you’re afraid or ashamed to deal with: ‘Everyone knows that writers who limit themselves in this way become trivial, repetitive and boring.’ And perhaps being trivial, repetitive and boring is the worst fate of all. In the end she can’t resist writing her Illyria story, but insists she won’t publish it. All writers know that’s self-delusion: writing without readers is like cooking without diners. Why go to the trouble? We all want readers. And sure enough, Janet soon admits that her Illyria story is going to be ‘too good not to publish’. For ‘Janet’ read ‘Alison’. Lurie visited Yaddo three times in the 1960s, and despite the taboo she described it so accurately that Real People is barely fiction. She doesn’t tell the literal truth ‒ that wouldn’t be enough. ‘The only reason for writing fiction at all is to combine a number of different observations at the point where they overlap. Fiction’, she adds, ‘is condensed reality.’ Perhaps the strange characters I met on my way here ‒ the big mama on her suitcase and the pregnant grandma with her gastric band ‒ aren’t real people at all. Perhaps I made them up. Perhaps I amalgamated them with other characters to heighten their effect. Or maybe they do exist, but are not who I imagined they were. I’m told Alison Lurie did not impress Yaddo’s then Director with her ‘condensed’ revelation of life in the colony. Records show she wasn’t invited back for eighteen years. Like Janet, her alter ego, she knew what she risked, but the material was too good to waste, and we, her readers, must be grateful for her sacrifice. As Janet sighs, in the end ‘Art has the last word.’Two of them are staring out of their windows. Two others are pacing about restlessly. One writes a letter, and signs it with a false name, while another reads (without permission) somebody else’s private correspondence. One is methodically bending a pile of his host’s coat hangers out of shape; one is picking out discords on a grand piano; and one, apparently, is making love to himself.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 49 © Helena Drysdale

About the contributor

Helena Drysdale, author of six strictly non-fiction books, is hoping she will be invited back to Yaddo.