What we used to call ‘the old road’ runs beside an ancient waterway that links the English Channel with the Sussex Weald. A thousand years ago one of the companions of the Conqueror fortified a bluff above the river, and sixty years ago the ruined walls of the Norman castle marked the beginning of a bicycle journey that my brother and I made each summer weekend to a grass-runwayed airfield at the river mouth.

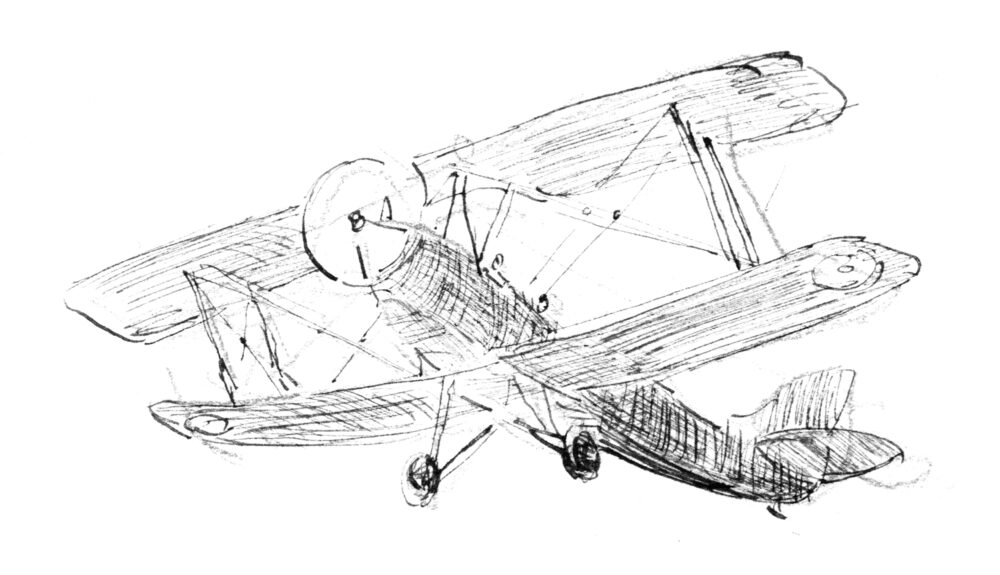

We would race past a Saxon church, its western hindquarters sunk into the hillside, a kindly beast emerging from its lair. We would teeter in slow motion beside the dark timbers of a medieval bridge. And by the time we dismounted to wheel our bicycles across the main road beneath the glass escarpment of a public school’s immense chapel, we would be looking seawards to the windsock of the airfield and skywards for the light aircraft – Tiger Moths, Chipmunks, Dragon Rapides – which were the objects of our plane-spotting pilgrimage.

I am reminded of those sunlit days, and of the ‘whooshpering’ sound of the canvas wings as the aircraft swept in above us, whenever I take down my copy of T. H. White’s England Have My Bones (1936). It is a book for browsing, for it takes the form of a journal which White kept through four seasons in 1934–5, the year he took flying lessons at a small airfield in the middle of England. Flying was his main summer activity; he spent the spring fishing for salmon in Scotland; the autumn rough shooting; the winter riding to hounds. The journal also contains delightful passages about entirely random matters. He writes about the grass snakes which he keeps loose in his study; about the surging kick of the super-charger on the engine of his Bentley; and about the effects of weather on mood: ‘If your senses become sharpened it generally means wet. Thus country people redouble their efforts at harvest if they can hear distant railways . . .’

Each of his journal entries can be savoured like a poem. T

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inWhat we used to call ‘the old road’ runs beside an ancient waterway that links the English Channel with the Sussex Weald. A thousand years ago one of the companions of the Conqueror fortified a bluff above the river, and sixty years ago the ruined walls of the Norman castle marked the beginning of a bicycle journey that my brother and I made each summer weekend to a grass-runwayed airfield at the river mouth.

We would race past a Saxon church, its western hindquarters sunk into the hillside, a kindly beast emerging from its lair. We would teeter in slow motion beside the dark timbers of a medieval bridge. And by the time we dismounted to wheel our bicycles across the main road beneath the glass escarpment of a public school’s immense chapel, we would be looking seawards to the windsock of the airfield and skywards for the light aircraft – Tiger Moths, Chipmunks, Dragon Rapides – which were the objects of our plane-spotting pilgrimage. I am reminded of those sunlit days, and of the ‘whooshpering’ sound of the canvas wings as the aircraft swept in above us, whenever I take down my copy of T. H. White’s England Have My Bones (1936). It is a book for browsing, for it takes the form of a journal which White kept through four seasons in 1934–5, the year he took flying lessons at a small airfield in the middle of England. Flying was his main summer activity; he spent the spring fishing for salmon in Scotland; the autumn rough shooting; the winter riding to hounds. The journal also contains delightful passages about entirely random matters. He writes about the grass snakes which he keeps loose in his study; about the surging kick of the super-charger on the engine of his Bentley; and about the effects of weather on mood: ‘If your senses become sharpened it generally means wet. Thus country people redouble their efforts at harvest if they can hear distant railways . . .’ Each of his journal entries can be savoured like a poem. Those that deal with flying were written after each lesson and are full of detailed notes. Sometimes the notes are exultant: ‘I like gliding turns; theoretically I rather like spins . . .’ Sometimes they are contrite: ‘This was a sad instructive lesson, but well worth having I suppose . . .’ They are both witty and surreal, and they uphold the aphorism of White’s alter ego in his most celebrated work The Once and Future King: ‘The best thing for being sad’, said Merlyn, ‘is to learn something . . .’ Such was the earnest accumulation of learning heaped up in these journal entries that one senses White must have been very sad indeed at this time. White’s reasons for taking flying lessons were various. There was a competitive instinct, in that a national newspaper was offering to pay the tuition expenses of any pupil at an English airfield deemed most promising by his flying instructor – evidence of growing public concern about Britain’s lack of preparedness for any future air war with Germany. Exhibitionism also played its part, because the image of the daring aviator coincided with a projection of dandyism which White liked to cultivate at the time. It meshed with the overall impression of a Bentley-driving, sharp-shooting, fly-tying, hardriding country gentleman with literary tastes: a useful persona for a freelance writer to convey to the class-conscious magazine editors of the time. But there were deeper psychological reasons. He was about to leave his job as a teacher at Stowe School in Buckinghamshire and was living in a cottage nearby with the intention of what today might be called ‘finding himself’. He may well have been anxious about the self that he would discover. Helen Macdonald’s recent H is for Hawk draws heavily on White’s exquisite monograph The Goshawk. She suggests its author channelled a tortured sexuality – of which he was becoming increasingly aware in the 1930s when he was undergoing psychoanalysis – into a complex devotional relationship with a bird of prey, a creature for whom killing is instinctive and without guilt. Macdonald affectionately calls him ‘Mr White’, and in her book he becomes a ghostly mentoring presence as she herself trains a goshawk and comes to terms with her grief at the death of her father. A few days after enrolling on the flying course White acknowledges, ‘I have always been a coward: afraid of things that hurt, body or soul . . . And now it is flying. I am afraid of aeroplanes. Because I am afraid of things, of being hurt and death, I have to attempt them . . .’ The suggestion that confrontation is a cure for cowardice is a dark foreshadowing of Merlyn’s aphorism about learning as a cure for sadness. In a sense White’s journal is about fear in every season of the year he chronicles. He is frightened not merely of death and injury, but – more subtly – that he will fail to gain acceptance by the people who are his sporting companions. In the spring he fears he will not be accorded respect by the ghillie who watches him cast over a salmon river; at the autumn pheasant-shoot he worries about not organizing the beaters properly; in the winter he urges his horse over a dangerous fence to impress the formidable elders of a fox-hunt. And in midsummer the respect he craves is that of his flying instructor: ‘I am terrified of Johnny, as everybody is; but with a curious confiding terror . . . I wouldn’t trust him with a farthing, a drink or my fiancée, but he could have my heart. It is like this with all good and great people . . .’ When, halfway through the course, the instructor lets slip that he has been the most promising student that season, White is ecstatic (it is not clear whether he went on to claim the newspaper’s contribution to his expenses). Gradually, under the instructor’s guidance, the pupil gains the ultimate acceptance, that of the flying machine itself. It is time to go solo. In a revealing touch White’s journal entry speaks of the plane and himself in the first person plural – as ‘we’ – during the final moments of his first solo flight: ‘We flattened, flattened, straight, perfect, touching, touching, tail, rumble, still straight, even on the ground, and not a bounce, not a bounce . . .’ He then switches to the third person singular in studied nonchalance: ‘He had done his solo. He shook hands with himself . . .’ By the end of the summer, with the mechanics of flight mastered, White is beginning to relax and look over the rim of his open cockpit with the eye of a writer. The details he picks out are those of the vanished world of the 1930s. He follows a railway line and overtakes an express train, the smoke pluming from the steam locomotive far below. ‘For a few seconds there was a red star, like the sun’s reflection from a conservatory roof, but strontium coloured. In fact I was looking down into the furnace of the railway engine’s boiler, a door about two feet square, from a height of nearly half a mile . . .’ He describes the enormous airship sheds at Cardington, and the pylons at Hatfield, bedecked like chivalric pavilions, round which the competitors in the King’s Cup air race flew in their dramatic racing turns. White’s flying instructor Johnny came second in the 1934 King’s Cup, flying his first heat in a July thunderstorm, and White was there to watch him: ‘nor could I give a true picture of the black sky out of which a tiny aeroplane draggled itself, lonely and exhausted. It was something about human splendour . . .’ As I lay on the grassy bank in the sunshine beside the river sixty years ago, I imagined that every plane that passed overhead was the focus of just such a drama. Every take-off, every swing round the airfield above the river and the castle and the Saxon church was special. The pilots may have been carrying out the routine ‘circuits and bumps’ required of every apprentice flyer – after all, the basic rule of aviation is that take-off is optional, while landing is compulsory – but to the youthful watcher these humdrum exercises had an epic quality. There was the sound. The thrumming of wires as the plane swooped overhead. The tick of the idling propeller. The shriek of the suspension at the point of touch-down. And then the flatulent surge of the engine striving to become airborne again. There was also the sight of flying machines whose designs – even in the 1950s – would have been familiar to White at his pre-war airfield. There were biplanes like the Tiger Moth, the lovely successor to the Gipsy Moth on which he learned to fly. And the Dragon Rapide, a passenger biplane whose Art Deco design – tapering wings with curved tips like those of dragonflies – was emblematic of the 1930s. Early each Saturday we bicycled to the aerodrome to watch the departure of the weekly flight to the Channel Islands, when the instruction aircraft suspended their humdrum activities and waited, like courtiers, for the regal passage of the Dragon Rapide into the western sky. I have always felt there is a yearning, aspirational quality about the sight and sound of light aircraft high in the summer sky; and from time to time I dip into England Have My Bones to recall the boyhood romance of watching a world of amateur flying in the 1950s which was not unlike the world of flying in the 1930s. Between those decades, of course, the nature of mainstream aviation had changed forever. The aviation war of the 1940s which some newspapers had foreseen when White decided to try and win his tuition expenses transformed flying. A year or two ago I had a long conversation with a remarkable man in the East Kent village where I live. Henry had been a Pathfinder pilot during the war, flying Lancaster bombers, and had been shot down over Berlin in 1944. He died in 2018 at the age of 96, and a villager leaving his memorial service was heard to remark, ‘We are pygmies on the shoulders of giants . . .’ In his mid-80s Henry took up flying again and went solo in a Piper Cub, one of the standard instruction aircraft of the modern flying club. ‘Don’t even think about the insurance!’ he told me during our conversation. I asked him to describe the difference between piloting a Lancaster during the war and flying a light aircraft today. He thought long and hard, and finally said, ‘Well, I suppose the Lancaster was like a combine harvester. The Cub is an autumn leaf . . .’ It was a deft comparison, and one to which the writer T. H. White – helmeted, goggled and gauntleted in his open cockpit – might well have given an aviator’s thumbs-up.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 66 © Andrew Joynes 2020

About the contributor

When he left the BBC, and a frenzied life as a current affairs producer, Andrew Joynes entered a reflective phase of existence. In his writing – as in his reading – he increasingly visits a vintage-stocked cellar of youthful memories of Sussex.