Across the east end of the nave of Canterbury Cathedral, where I was a volunteer guide for over a decade, there is a stone strainer arch erected by Prior Thomas Goldstone 500 years ago. It is a kind of tiebar, one of six which bind together the columns that support Bell Harry Tower, the cathedral’s dominant feature. The arch is essential to the integrity of the building’s central structure and is decorated with flowered designs and an inscription. On either side of the Prior’s initials and his rebus – three golden pebbles, a visual pun on his surname – there is the first verse of the psalm that begins Non nobis Domine (‘Not unto us, O Lord, but unto thy name give glory . . .’).

In this way Prior Goldstone acquired a double helping of renown. He has been advertised down the centuries – on a kind of prominent stone billboard – both as the patron of a striking architectural achievement and as the humble instrument of God’s intentions for His great church. During the so-called Age of Faith before the Reformation, pious self-deprecation could also mean tacit self-congratulation.

When I took groups of visitors round the cathedral, I would often refer to the motivation of the great ecclesiastical patrons like Thomas Goldstone. And I would sometimes suggest that those interested should get hold of a copy of William Golding’s novel The Spire (1964) whose protagonist Dean Jocelin embarks, like Prior Goldstone, on a quest for personal renown through divine favour by obsessively driving forward an architectural project. Jocelin’s intention is to have a great spire built above his cathedral. In the end the endeavour will destroy him.

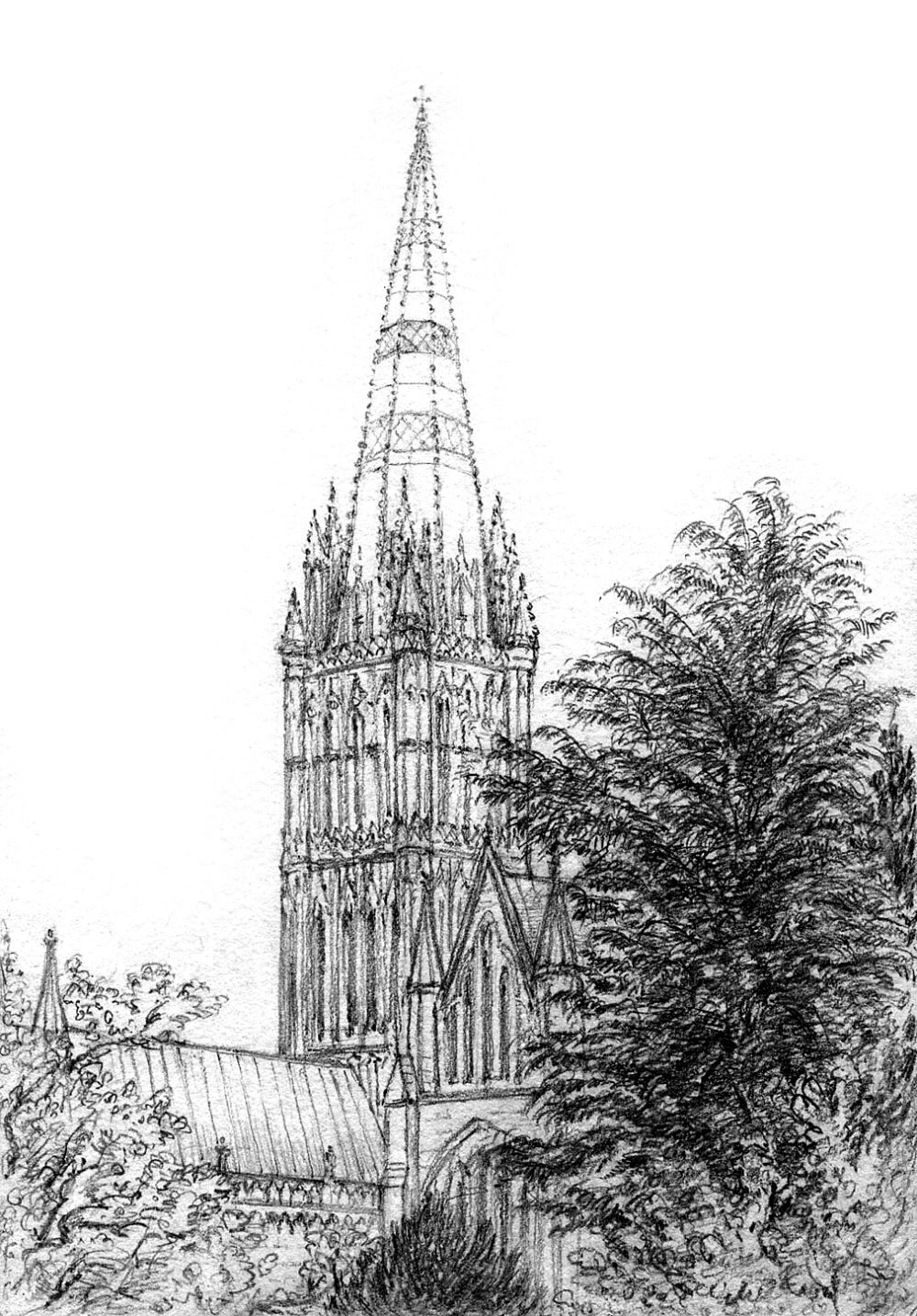

Although Golding does not identify the cathedral about which he is writing, it is generally thought to be Salisbury, where he taught at a grammar school in the cathedral close for a decade

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inAcross the east end of the nave of Canterbury Cathedral, where I was a volunteer guide for over a decade, there is a stone strainer arch erected by Prior Thomas Goldstone 500 years ago. It is a kind of tiebar, one of six which bind together the columns that support Bell Harry Tower, the cathedral’s dominant feature. The arch is essential to the integrity of the building’s central structure and is decorated with flowered designs and an inscription. On either side of the Prior’s initials and his rebus – three golden pebbles, a visual pun on his surname – there is the first verse of the psalm that begins Non nobis Domine (‘Not unto us, O Lord, but unto thy name give glory . . .’).

In this way Prior Goldstone acquired a double helping of renown. He has been advertised down the centuries – on a kind of prominent stone billboard – both as the patron of a striking architectural achievement and as the humble instrument of God’s intentions for His great church. During the so-called Age of Faith before the Reformation, pious self-deprecation could also mean tacit self-congratulation. When I took groups of visitors round the cathedral, I would often refer to the motivation of the great ecclesiastical patrons like Thomas Goldstone. And I would sometimes suggest that those interested should get hold of a copy of William Golding’s novel The Spire (1964) whose protagonist Dean Jocelin embarks, like Prior Goldstone, on a quest for personal renown through divine favour by obsessively driving forward an architectural project. Jocelin’s intention is to have a great spire built above his cathedral. In the end the endeavour will destroy him. Although Golding does not identify the cathedral about which he is writing, it is generally thought to be Salisbury, where he taught at a grammar school in the cathedral close for a decade and a half from the late 1940s (his observation of the boys’ playground behaviour is said to have inspired his early novel Lord of the Flies). Salisbury Cathedral has the tallest spire in the country – 404 feet high – and when its first incarnation was built in the fourteenth century there must have been the same sense of disquiet within the cathedral community – mutters about overweening pride and dark references to the Tower of Babel – that the fictional Dean Jocelin encounters at the outset of the novel. Jocelin is never off-stage, and every development in the plot is filtered through his frame of mind, from ecstatic exultation at curtain-up to self-doubt by the interval and eventually to despair and madness at the finale. He is taken to a very high place and is cast down, and the ascent and fall are to a large extent of his own making. From the outset, Golding makes it clear that the presence of the masons building Jocelin’s spire is disrupting the smooth order of the cathedral. The removal of walls changes the devotional nature of the building’s interior, and even the Dean is aware that, until the spire on which he has set his heart has been built, the change will be for the worse.Facing that barricade of wood and canvas I could think this was some sort of pagan temple; and those two men posed so centrally in the sun dust with their crowbars were the priests of some outlandish rite . . .The masons pitilessly bully one of the cathedral’s sweepers, and when the Dean remonstrates with the master builder, he is told that this is their way of warding off bad luck. They down tools on the pre-Christian Midsummer Night feast, and their celebratory fires burn on the hills surrounding the city. ‘They are dangerous men, strange creatures from every end of the world, and seem willing to resort to violence at the slightest provocation . . .’ It is Jocelin’s relationship with Roger Mason the master builder that provides the pivot – almost like one of the masons’ engineering devices – around which the novel’s plot turns. At first the builder, conscious that nothing on the scale of the spire has been attempted before, is contemptuous of the cleric’s insistence that faith will be sufficient to drive the project forward. He has the caution of a practical man, setting out his plumb lines and saucers of water to detect any buckling of the supporting pillars under the increasing weight of the spire as it rises. There is an extraordinary scene where the two men, surrounded by labourers and clerics and townspeople, peer into the enormous pit which has been dug at the centre of the crossing to strengthen the pillars’ foundations. The rainwater is rising; there is a stench of rotting graves; and as lighted candles are lowered into the pit it can be seen that the earth itself is moving under the weight of the spire: ‘some form of life, that which ought not to be seen or touched, the darkness under the earth, turning, seething, coming to the boil . . .’ Roger wants to abandon the project at this point, but for some time the Dean has been aware that the master builder is in love with the cathedral sweeper’s wife. He has not spoken out against this, as a devout churchman should have done, because he realizes this is a way of putting pressure on the man (‘She will keep him here . . .’). On wooden scaffolding high in the air, as the ravens swoop and croak around them, as the stones at the base of the spire vibrate eerily, ‘singing’ under the pressure of the weight bearing down upon them, and as the pinnacles and glass and metal of the nearly completed spire sway in the wind, the two men confront each other. Eventually Jocelin’s will prevails. ‘So he began to climb down the ladders with his angel; and before he was out of sight he heard Roger Mason speaking softly. “I believe you’re the devil. The devil himself” . . .’ The spire continues to rise, but Jocelin’s world falls. He suffers from a deterioration of the spine, a cancer perhaps, which until now has given him a sense that a supernatural being is standing just behind him, willing him on. Now the angel at his back becomes a debilitating fire. His opponents in the cathedral chapter, alarmed at the Dean’s heedless persistence with an increasingly expensive and dangerous project, have made representations to Rome, and a Papal Visitor arrives to investigate. Most damaging of all to Jocelin’s self- esteem, it emerges that he owes his high ecclesiastical position not to his innate ability or to divine favour, but to an act of nepotism. Though he does not know it, his well-connected aunt was once the mistress of the king, who as patron of the cathedral granted her request for a senior position for her nephew: ‘We shall drop a plum in his mouth.’ The rest of the cathedral chapter know of this connection, which explains the reserve bordering on contempt with which they treat their Dean from the start of the novel. The Visitor removes Jocelin from office. He becomes a non-person. Once, in the early days of his building project, he had planned to have a sculpted head-and-shoulders image of himself placed at each of the four corners of the crossing which support the spire. He would be depicted in the guise of an angel, long hair streaming behind him in the celestial wind: thus, like Prior Goldstone at Canterbury, he would be advertised down the centuries as the God-favoured patron of a great architectural work. Now the fallen Dean does indeed have long hair, but it is straggling and uncombed. He is a wild-eyed, forlorn figure, and there is no angelic radiance in his careworn face. Even on his deathbed, he asks repeatedly about the building work. Has the spire fallen? There is a smile from the kindly chaplain whom Jocelin used to treat so condescendingly in his glory-days. ‘Not yet,’ he replies. The Spire is a complex book, and it challenges the complacent assumption that the great cathedrals arose because of the simple religious faith of their builders. In the so-called Age of Faith the motivation of the grand ecclesiastical patrons contained quite as much egoism and ambition – and debate about their favoured pro-jects contained quite as much back-biting and malice – as would be the case in our own rootless times. When I was at a training session for Canterbury guides some years ago, I was told a story about cathedral tourism. A young priest at Salisbury was confronted late one summer afternoon by an elderly American lady who was clearly at the end of her sightseeing tether. The ‘Cotswolds and Back’ excursion from London had made for a very long day, and as she staggered into the sunlit nave, beneath the highest cathedral spire in England, she asked with a weary desperation, ‘Is this Stonehenge?’ Then, soon after I became a guide, a young mother came into Canterbury Cathedral with a child in a pushchair. She told me that ever since he could stand up in his cot, little Ernest had looked out of his bedroom window at the cathedral’s Bell Harry Tower. He was fascinated by its spires and pinnacles, glimpsed far away across the rooftops. Between them, mother and son contrived a bedtime story about the cathedral. It was, they concluded, a magical creature of great power and beauty – a Big Friendly Dragon, perhaps – which long ago settled in the city and brought good fortune to its people. Now, on a winter’s afternoon, the mother had brought her child into the darkened nave to visit the BFD for the first time. The child looked around excitedly, and the flickering light of the candles reflected in his eyes. To me, these are endearing stories. They express the ‘otherness’ of a great cathedral as it is perceived today, and as it is presented in William Golding’s subtle and instructive novel. Whether it is seen as a mystical assembly of stone with an aura of antiquity, as a fabled creature in a bedtime story, or as an example of enduring cultural endeavour – serving perhaps as a reprimand to our restless and inattentive times – the thought of the medieval cathedral continues to loom over the modern imagination, much as the dominating vision of his spire did over the deathbed of Dean Jocelin. A cathedral used to be regarded as a kind of ark, a place of power and refuge. Has that essential idea of a great cathedral fallen? Not entirely, perhaps. ‘Not yet.’

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 71 © Andrew Joynes 2021

About the contributor

Andrew Joynes estimates that during his time as a guide he conducted some 6,000 visitors round Canterbury Cathedral. He suggests that studying the Middle Ages is like reversing a telescope: the entire scene appears in miniature; the figures are sharply delineated; and their relationship to each other can be precisely and easily traced.