‘Flashman is back,’ declared the Labour leader Ed Miliband at Prime Minister’s Questions on 11 May 2011. He was referring to David Cameron and he presumably meant to imply that the Tory was a boorish, ill-mannered bully, riding roughshod over the finer feelings of his Parliamentary colleagues. But I did wonder at the time just how well-chosen Miliband’s ‘insult’ really was. Wouldn’t any male politician be secretly thrilled to be likened to Harry Paget Flashman, the fictional Victorian soldier and adventurer?

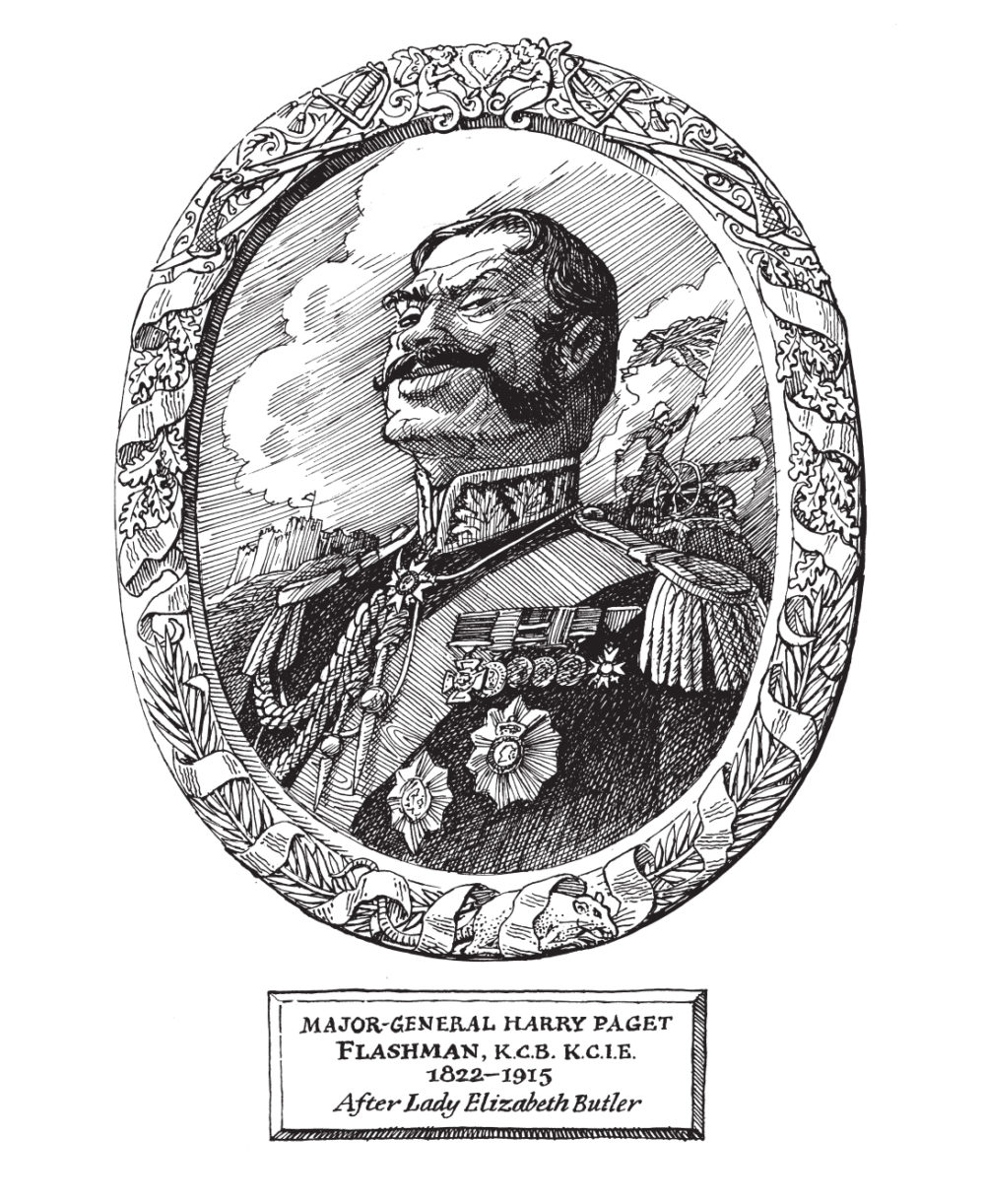

True, Flashman is a bully, a liar, a coward and a cad – not qualities our leaders would normally want ascribed to them – but, damn it, he’s a handsome fellow, square-jawed, walrus-whiskered, sword adangling beside a thrust-out pelvis encased in the finest breeches since Colin Firth made the ladies faint as Darcy. Wearing the self-satisfied grin of a man who’s just spent the night with a grateful virgin or two . . . what man wouldn’t want to be Flashman?

For here’s another thing about Flashy: he’s a quite phenomenal babe-magnet. In the pages of fiction only Don Juan and James Bond can match Flashman’s prodigious sexual success. From prostitutes to princesses, Harry’s had ’em all. He’s rutted with Calcuttan dancing-girls and squired Native American squaws; been ravished by Ranavalona I, the savage queen of Madagascar; seduced Lillie Langtry, the celebrated actress and mistress of Edward VII; and run through most of the Kama Sutra with Jind Kaur, the Maharani of Punjab. He once noted that his favourite lovers were Lakshmi Bai, Rani of Jhansi, the Chinese Dowager Empress Cixi, and Lola Montez, the latter ‘a Queen, an Empress, and the foremost courtesan of her time’. Halfway through his life he counted up 478 conquests. He was married, too.

In fairness, perhaps Miliband was referring to the Flashman of Tom Brown’s Schooldays, the insufferably preachy work by Thomas Hughes in

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign in‘Flashman is back,’ declared the Labour leader Ed Miliband at Prime Minister’s Questions on 11 May 2011. He was referring to David Cameron and he presumably meant to imply that the Tory was a boorish, ill-mannered bully, riding roughshod over the finer feelings of his Parliamentary colleagues. But I did wonder at the time just how well-chosen Miliband’s ‘insult’ really was. Wouldn’t any male politician be secretly thrilled to be likened to Harry Paget Flashman, the fictional Victorian soldier and adventurer?

True, Flashman is a bully, a liar, a coward and a cad – not qualities our leaders would normally want ascribed to them – but, damn it, he’s a handsome fellow, square-jawed, walrus-whiskered, sword adangling beside a thrust-out pelvis encased in the finest breeches since Colin Firth made the ladies faint as Darcy. Wearing the self-satisfied grin of a man who’s just spent the night with a grateful virgin or two . . . what man wouldn’t want to be Flashman? For here’s another thing about Flashy: he’s a quite phenomenal babe-magnet. In the pages of fiction only Don Juan and James Bond can match Flashman’s prodigious sexual success. From prostitutes to princesses, Harry’s had ’em all. He’s rutted with Calcuttan dancing-girls and squired Native American squaws; been ravished by Ranavalona I, the savage queen of Madagascar; seduced Lillie Langtry, the celebrated actress and mistress of Edward VII; and run through most of the Kama Sutra with Jind Kaur, the Maharani of Punjab. He once noted that his favourite lovers were Lakshmi Bai, Rani of Jhansi, the Chinese Dowager Empress Cixi, and Lola Montez, the latter ‘a Queen, an Empress, and the foremost courtesan of her time’. Halfway through his life he counted up 478 conquests. He was married, too. In fairness, perhaps Miliband was referring to the Flashman of Tom Brown’s Schooldays, the insufferably preachy work by Thomas Hughes in which Flashman is chief tormentor of the ‘fags’ at Rugby School and a bully of the first order. Whatever the case, the fact is that the author George MacDonald Fraser adopted Hughes’s Flashman, bestowed the forenames Harry and Paget upon him, gave him a lifespan (1822–1915) and sent him off to conquer the world of blood-and-thunder Victorian adventure fiction in an extraordinary series of cult novels. And it is this Flashman who will spring to mind among the vast majority of British voters for whom the name means anything at all. In the first book in the series, Flashman (1969), Fraser purported to have ‘discovered’ Flashman’s papers in an antique tea-chest in a Leicestershire saleroom, and he presented himself as their editor rather than their author. The faux-scholarly style, complete with extensive factual footnotes and appendices, and the references to genuine historical figures and events, convinced a number of reviewers in the USA (several of them academics) that Flashman was the real memoir of a soldier in the First Anglo-Afghan War. Which is extraordinary, because Fraser’s second masterstroke is that, though a risible coward wholly lacking in moral fibre, by a series of flukes, bluffs and coincidences, in every one of the twelve novels Flashman always ends up looking like a hero. By ‘turning tail and lying and posturing and pinching other chaps’ credit’, he generally emerges with the girl, the swag and another medal for valour. Those who see through his bluster and spot the craven rascal beneath have an unfortunate habit of popping their clogs before he can be exposed. Not that Flashman doesn’t suffer along the way. Over the course of the series he becomes embroiled in virtually every military misadventure of the nineteenth century, including the Retreat from Kabul, the Charge of the Light Brigade, the Indian Mutiny and Custer’s Last Stand. Here I must admit that nearly everything I know about Victorian international affairs I’ve learned from the Flashman series. Given that they are ultimately a set of derring-do pastiches, this is an odd admission to make. But Fraser’s attention to period detail and his ability to conjure up a place and a time rank him alongside the finest historical novelists. Since Flashman presents his own character at its very worst in these ‘confessional’ journals, we are inclined to believe him; and when his narrative wanders from verifiable historical fact Fraser ‘corrects’ him in the footnotes. Before reading Flashman and the Dragon (1985), for example, I had never known of the enormity of China’s Taiping Rebellion. In it at least 20 million people died – more deaths than in the First World War that followed over five decades later. Though they rattle along at a furious pace, Fraser’s novels aren’t for the squeamish. The setting of Flash for Freedom (1971), for example, is the African-American slave trade and the novel contains not only a stream of shocking scenes but also the highest incidence of the ‘nword’ in any book I’ve ever read. In Flashman and the Great Game (1975), the horrors of the Siege of Cawnpore – an episode in the Indian Mutiny when 120 British women and children were massacred by sepoys and their hacked-up remains thrown into a well – are recounted in grisly detail. Fraser is utterly unsparing in his depiction of man’s inhumanity to man; of our sad species at its basest. This might suggest that George MacDonald Fraser was a misanthrope. He may well have been; certainly he believed that Britain had gone to the dogs by the 1970s and then got progressively worse. During the decades before his death in 2008 he lived on the Isle of Man (which only abolished the birching of petty criminals in 2000), from where he opposed the conversion to metric measurement and emitted, between Flashman novels, eye-watering tirades against political correctness. This is not to dismiss Fraser as a Colonel Blimp, nor to suggest that he shared the views of his whoring, racist, sexist literary creation. Rather, he was an idiosyncratic individual who loathed the stifling conformity of the liberal Left, which he saw as crushing personal freedom of thought and expression. Fraser’s own life was extraordinary enough. Born in Carlisle in 1925 to Scottish parents, he enlisted at the age of 18 in the Border Regiment and served in Burma during the Second World War, an episode recounted in his remarkable memoir, Quartered Safe Out Here (see p.50). Later in life he found himself mingling with the Hollywood A-list, for he wrote a number of movie scripts, including those for Octopussy and The Three Musketeers. But it was the Flashman series which established his fame, and which will surely ensure his immortality. For, as devotees of the series know, beneath the raw comedy and the thumping action, beneath the sex and violence and Flashy’s appetite for devilment, there is another strand, one which becomes increasingly apparent through the series. Contrary to their reputation, there is a strong streak of moral rectitude in Fraser’s books. Because his own persona is all bluff, Flashy is able to see through every set of Emperor’s New Clothes he encounters. His evaluations of bureaucratic folly are as clear-eyed as any great parodist, and he doesn’t have much time for armchair generals either. Consider this from Flashman at the Charge (1973), before the Light Brigade sets off on its doomed charge towards the Russian guns at Balaclava:There speaks the voice of a real soldier – here, we suspect, Flashman is Fraser. Flashy also has a decidedly no-nonsense view of historical theories. How’s this for a succinct, iconoclastic summary of the causes of the American Civil War, from Flashman and the Angel of the Lord (1994)?I’ll tell you something else, which military historians never realise: they call the Crimea a disaster, which it was, and a hideous botch-up by our staff and supply, which is also true, but what they don’t know is that even with all these things in the balance against you, the difference between hellish catastrophe and brilliant success is sometimes no greater than the width of a sabre blade, but when all is over no one thinks of that. Win gloriously – and the clever dicks forget all about the rickety ambulances that never came, and the rations that were rotten, and the boots that didn’t fit, and the generals who’d have been better employed hawking bedpans round the doors. Lose – and these are the only things they talk about.

For all his misdemeanours, Flashman is surrounded by figures who are far worse, from Ranavalona I to Otto von Bismarck. All Flashy wants to do is to save his own skin and bed a few birds; his antagonists tend to want to flay everyone alive, either from a misguided sense of duty or simply because they are psychopaths. Above all, Flashman detests idealistic or nationalistic baloney, the hope-andglory huff-puffery that prompts military leaders to send droves of young men to useless suffering and death in the face of all common sense. Take this view of the American War of Independence, again from Flashman and the Angel of the Lord:As you know, it was slavery that drew the line and led to the war, but not quite in the way that you might think. It wasn’t only a fine moral crusade . . . the fact is that America rubbed along with slavery comfortably enough while the country was still young . . . it was only when the free North and the slave South discovered that they had quite different views about what kind of country the USA ought to be that the trouble started. Each saw the future in its own image: the North wanted a free society of farms and factories devoted to money and Yankee ‘know-how’ and all the hot air in that ghastly Constitution, while the South dreamed, foolishly, of a massa paradise where they could make comfortable profits from inefficient cultivation, drinking juleps and lashing Sambo while the Yankees did what they dam’ well pleased north of the 36° 30´ line.

Point out [to an American] that Canada and Australia managed their way to peaceful independence without any tomfool Declarations or Bunker Hills or Shilohs or Gettysburgs, and are every bit as much ‘the land of the free’ as Kentucky or Oregon and all you’ll get back is a great harangue about ‘liberty and the pursuit of happiness’, damn your Limey impudence . . . You might as well be listening to an intoxicated Frog.

It’s understandable, to be sure: they have to live with their ancestors’ folly and pretend it was all for the best, and that the monstrous collection of platitudes which they call a Constitution, which is worse than useless because it can be twisted to mean anything by crooked lawyers and grafting politicos, is the ultimate human wisdom. Well it ain’t, and it wasn’t worth one life, American or British, in the War of Independence, let alone the vile slaughter of . . . the Civil War.

Romantic it isn’t, but it makes you think. Ed Miliband meant to demean the Prime Minister by comparing him to Flashman. Yet we might ask: what would the world be like if all leaders really were more like Flashman? What, in fact, would it be like if everyone was like Flashman? Certainly there’d be a lot more philandering and infidelity and running away in the world, but it would also be a far less bloody place. Flashman is a soldier wholly without idealistic fervour and warlike instincts; if he had his way there’d have been no disaster at Balaclava, no massacre at Cawnpore, no slaughter at Little Bighorn; instead, men would be left to get on with their drinking, gambling, lechery and whoring in peace.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 33 © Andrew Nixon 2012

About the contributor

Andrew Nixon is editor of ‘The Dabbler’ culture blog: www.thedabbler.co.uk.