In the end, it was no surprise that I turned to books in the aftermath of my father’s death; as much as anything else, a love of reading, and a confidence in the calming power of the written word, was one of the many things that he gave me. What was more unexpected was the identity of the book that offered the greatest solace.

My first ports of call were natural enough places to turn, and all of them did help. Dad was reading Jan Morris’s tiny book on the vast Japanese battleship Yamato the day before he died, and so that was where I started. In later weeks I picked up James Agee’s A Death in the Family, Max Porter’s Grief Is the Thing with Feathers and William Wharton’s extraordinary Dad, an author whom I love, but a book which I don’t think I’ll ever be able to pick up again without a great deal of pain.

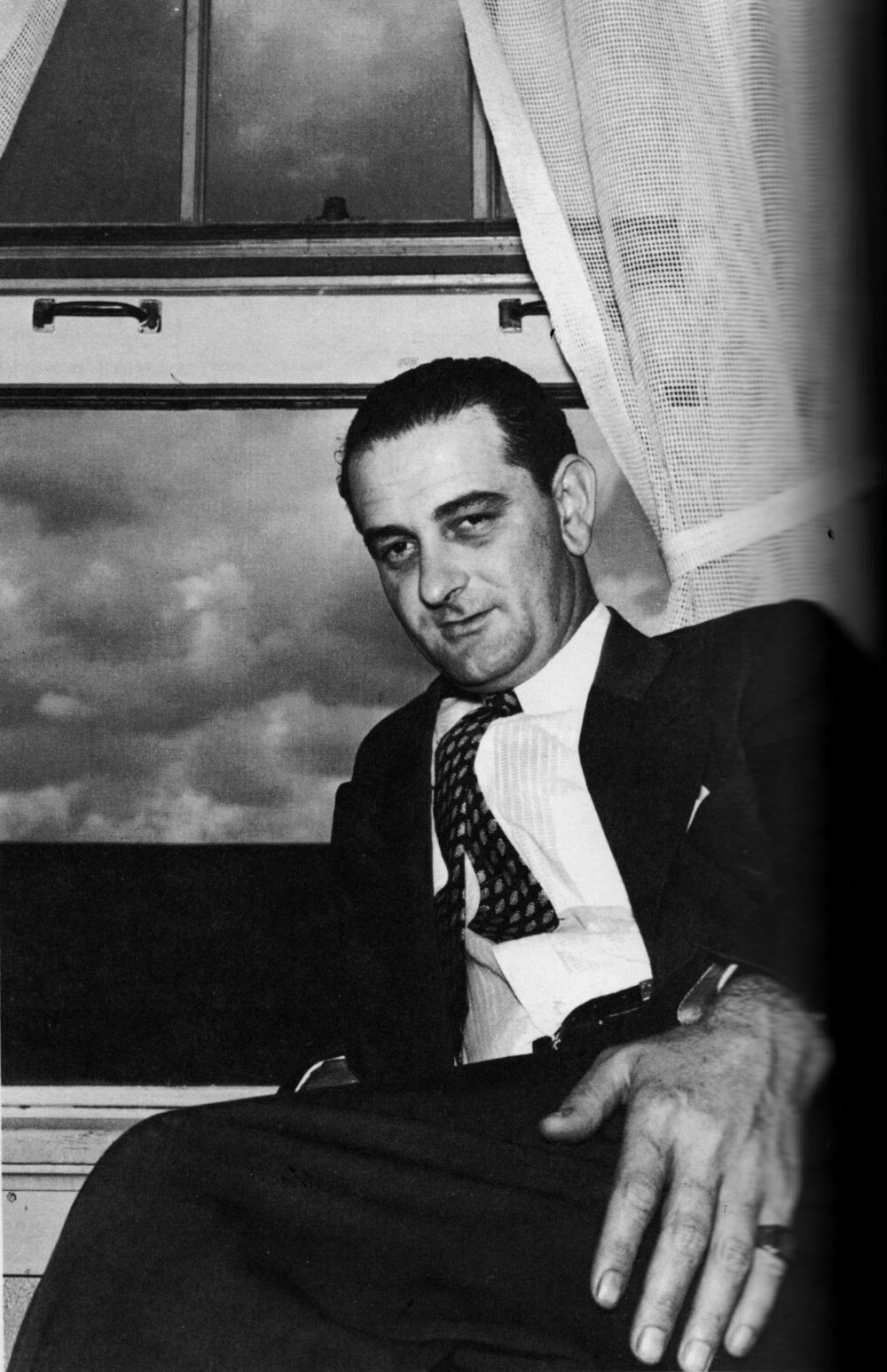

Each of these rendered loss in terms that were helpful, and of course my reading of each was supercharged with a sort of hyper- sensitivity, and I think I left a little of my hurt in the pages of each of them. On the train to the funeral, I read Geoff Dyer’s Broadsword Calling Danny Boy, about that iconic war film Where Eagles Dare, and laughed out loud much of the way there, which is not something I would have thought possible. But in some ways the book – or rather books – that did most to lift me out of the gloom came in the most unexpected form: Robert Caro’s four-volume (thus far) biography, The Years of Lyndon Johnson.

Caro’s biography is undoubtedly one of the monuments of American political writing in the modern age. Consisting to date of The Path to Power

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inIn the end, it was no surprise that I turned to books in the aftermath of my father’s death; as much as anything else, a love of reading, and a confidence in the calming power of the written word, was one of the many things that he gave me. What was more unexpected was the identity of the book that offered the greatest solace.

My first ports of call were natural enough places to turn, and all of them did help. Dad was reading Jan Morris’s tiny book on the vast Japanese battleship Yamato the day before he died, and so that was where I started. In later weeks I picked up James Agee’s A Death in the Family, Max Porter’s Grief Is the Thing with Feathers and William Wharton’s extraordinary Dad, an author whom I love, but a book which I don’t think I’ll ever be able to pick up again without a great deal of pain. Each of these rendered loss in terms that were helpful, and of course my reading of each was supercharged with a sort of hyper- sensitivity, and I think I left a little of my hurt in the pages of each of them. On the train to the funeral, I read Geoff Dyer’s Broadsword Calling Danny Boy, about that iconic war film Where Eagles Dare, and laughed out loud much of the way there, which is not something I would have thought possible. But in some ways the book – or rather books – that did most to lift me out of the gloom came in the most unexpected form: Robert Caro’s four-volume (thus far) biography, The Years of Lyndon Johnson.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 69 © Andy Merrills 2021

About the contributor

Andy Merrills lives in Leicester and is eagerly awaiting Volume 5 of the Caro biography. He teaches ancient history and is currently writing a book about a forgotten Latin epic.

Comments & Reviews

Leave a comment

Sign up to our e-newsletter

Sign up for dispatches about new issues, books and podcast episodes, highlights from the archive, events, special offers and giveaways.