When he was asked to update The Making of the English Landscape by W. G. Hoskins, Christopher Taylor described it as ‘one of the greatest history books ever written’. I may not have appreciated that when I bought the original version as a modest Pelican paperback in 1975 but, like any self-absorbed teenager, I was convinced of its importance to me. It was a revelation, confirming and explaining things dimly sensed yet intensely felt, and it settled deeply into my consciousness, permanently altering the way I looked at the world.

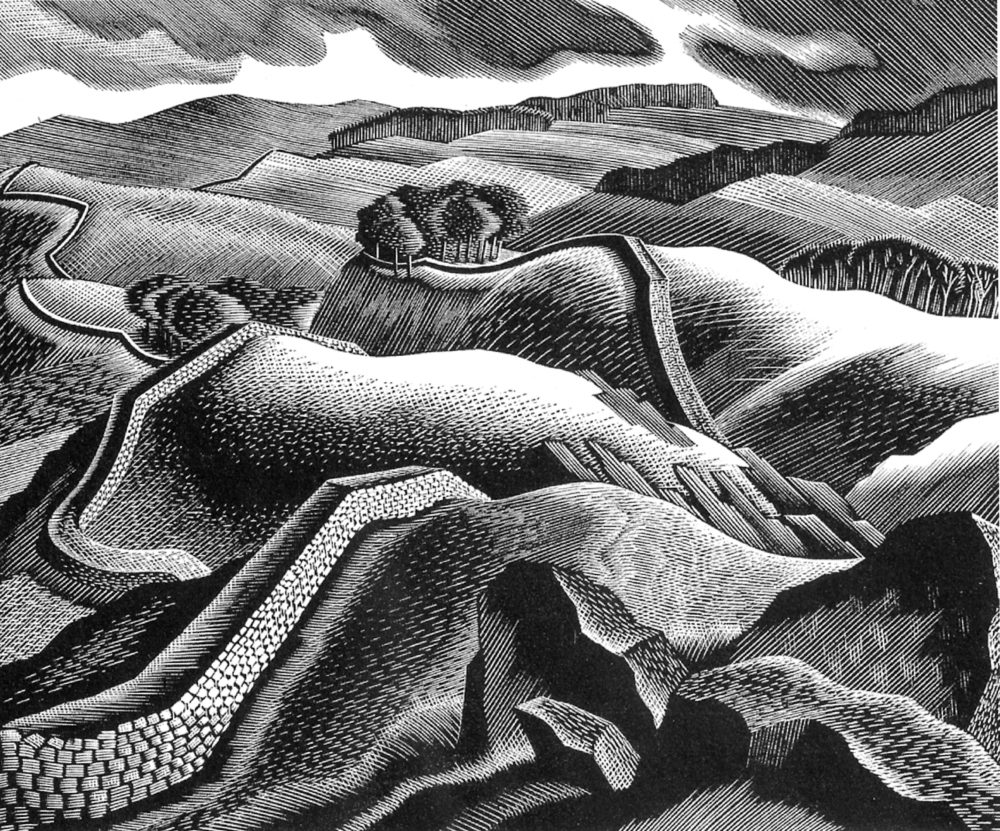

Hoskins pioneered the study of the landscape at the University of Leicester. His book appeared in 1955, the only one of its kind. In clear and elegant prose he described how lanes and hedges, copses, farmsteads, fields and place names could tell the story of the past and explain the configuration of the present. His fascination with and evident delight in such details as Anglo-Saxon estate boundaries, ridge-and-furrow field patterns and the street plans of medieval towns spoke from the page, and the grimy quality of the dated black-and-white photographs only strengthened the spell he cast.

For a teenager growing up on Dartmoor, in the midst of layers of history on an ancient landscape, this was as gripping as a good novel: more so, perhaps, because it brought my surroundings to life. Ever since I had known any local history, I had longed to be able to step back a few centuries, to see people working the now ruinous marginal farms, watch tinners ‘streaming’ on the high moor and 18 understand the way of life of prehistoric people in their huts and granite pounds. Hoskins was a Devon man and used plenty of Devon examples in his book, which helped, but his descriptions were also intensely evocative, making it easy to picture a landscape as it once had been, and to ‘read’ what was left.

Half a century on from publication, the view is far less clear. The discipline he so successfully established has attracted many others whose work has revealed a more complex picture than the one he painted. Publications on t

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inWhen he was asked to update The Making of the English Landscape by W. G. Hoskins, Christopher Taylor described it as ‘one of the greatest history books ever written’. I may not have appreciated that when I bought the original version as a modest Pelican paperback in 1975 but, like any self-absorbed teenager, I was convinced of its importance to me. It was a revelation, confirming and explaining things dimly sensed yet intensely felt, and it settled deeply into my consciousness, permanently altering the way I looked at the world.

Hoskins pioneered the study of the landscape at the University of Leicester. His book appeared in 1955, the only one of its kind. In clear and elegant prose he described how lanes and hedges, copses, farmsteads, fields and place names could tell the story of the past and explain the configuration of the present. His fascination with and evident delight in such details as Anglo-Saxon estate boundaries, ridge-and-furrow field patterns and the street plans of medieval towns spoke from the page, and the grimy quality of the dated black-and-white photographs only strengthened the spell he cast. For a teenager growing up on Dartmoor, in the midst of layers of history on an ancient landscape, this was as gripping as a good novel: more so, perhaps, because it brought my surroundings to life. Ever since I had known any local history, I had longed to be able to step back a few centuries, to see people working the now ruinous marginal farms, watch tinners ‘streaming’ on the high moor and 18 understand the way of life of prehistoric people in their huts and granite pounds. Hoskins was a Devon man and used plenty of Devon examples in his book, which helped, but his descriptions were also intensely evocative, making it easy to picture a landscape as it once had been, and to ‘read’ what was left. Half a century on from publication, the view is far less clear. The discipline he so successfully established has attracted many others whose work has revealed a more complex picture than the one he painted. Publications on the subject tend to be more circumspect, as well as more specialized: one can find books on the history of hedges, or the archaeology of Bronze Age field systems, but nothing that tries to give the overview that Hoskins provided. Indeed, I doubt if anyone now would dare to write such a book. Taylor (himself author of, among other things, Fields in the English Landscape and Roads and Tracks of Britain) suggested that Hoskins was ‘the last of the polymaths’. Hoskins wrote a new introduction to the 1977 edition of his book, in which he acknowledged that fresh work was already yielding much ‘new and often unexpected’ information, particularly through archaeology. Even though he knew that ‘the landscape is older than we think’, he had not foreseen that its basic field and road patterns may have been laid down before Roman times; or that the clearing of the primeval forest, which he describes so vividly, might have been complete by the time of the Domesday Book. Fortunately, he did not succumb to the temptation to revise The Making of the English Landscape. It might be thought necessary, he wrote in 1977, ‘but there is so much we still do not know, so much work in progress, that a revision is still premature’. Not only would it have been unnecessary; it would have muddied the sparkling waters of his original text. Better to do as his publishers Hodder & Stoughton did eleven years later, when they saw that the book was worth republishing for a new generation of readers. They produced a large-format hardback with striking colour plates to attract buyers and a useful new introduction and commentary by Christopher Taylor. This 1988 edition, with its heavy covers and rather busy layout, never appealed to me as its paperback forerunner had. The Pelican book, perhaps because of its limitations, had the effect of inspiring the reader to get out and do what Hoskins himself evidently so enjoyed and recommended: see the landscape on foot, having first pored over a one-inch Ordnance Survey map ‘which one can sit down and read like a book for an hour on end, with growing pleasure and imaginative excitement’. Is The Making of the English Landscape required reading for rural campaigners? If not, it should be. An underlying theme of the book is that change has come surprisingly quickly to the countryside at various points in its history. Forest clearance, open field systems, depopulation and population growth, enclosure and industrialization have all altered its appearance, sometimes within a couple of generations, creating shaky ground for anyone who asserts that the countryside should remain ‘as it has always been’. However, those changes have always left their marks on the landscape. Hoskins delighted in evidence of what he described as the ‘hand-made scale of that early world’; but he clearly loathed what had happened to industrialized cities and to the landscape as a whole in the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when for the first time the scale of change threatened the older landscape with total obliteration. Despite a rigorous approach – he dismissed as ‘sentimental and formless slush’ the sort of books concerned only with superficial appearances – he seems to have been unable to discern anything positive in the developments of his own lifetime, writing that ‘especially since the year 1914, every single change in the English landscape has either uglified it or destroyed its meaning, or both . . . Demos and Science are the joint Emperors’. It’s hard not to feel some sympathy with his view, particularly from the vantage point of the early twenty-first century. The study of landscape history is effectively a fascination with change, but one can scarcely feel enthusiasm for hundred-acre business parks, motorway service stations and the insidious spread of street furniture – the touch of ‘the acid fingers of the twentieth century’. But perhaps future historians will feel that such developments are all part of what Hoskins described by likening the English landscape to a symphony. One may enjoy it ‘as an architectural mass of sound’, he wrote, or, by isolating the different themes as they enter, ‘see how one by one they are intricately woven together and by what magic new harmonies are produced’.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 4 © Annabel Walker 2004

About the contributor

Annabel Walker is a journalist and writer who has enjoyed landscapes as far afield as western China in the course of her career, but she has somehow never managed to fulfil her youthful ambition to write about Dartmoor.