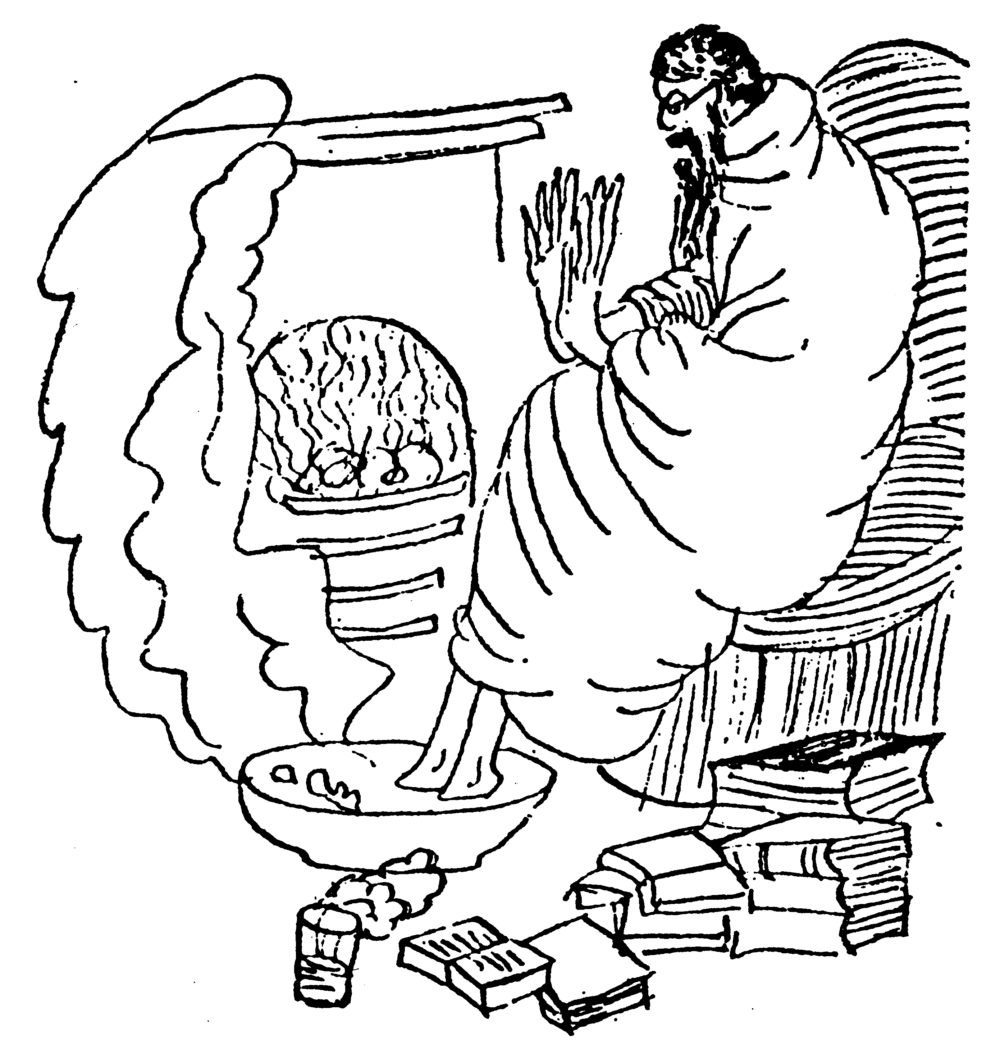

On New Year’s Day 1917 Carrington noted in her diary that her portrait of Lytton Strachey was finished; knowing her achievement, she hugged it to herself. ‘I should like to go on always painting you every week, wasting the afternoon loitering, and never, never, showing you what I paint . . .’ Today her loving tribute is on display in the National Portrait Gallery – an exception for this ambitious yet secretive painter, whose work rarely appears in public collections.

In the tsunami of Bloomsburiana launched by Michael Holroyd’s masterly biography of Strachey (1969), Dora Carrington mostly plays a bit part outside the core group of radical artists and thinkers, through her all-consuming attachment to Strachey, who was at its epicentre. Months after painting his portrait she famously defied her family, besotted suitors and the terrifying consensus of his friends to set up home in the country with the stork-limbed, semi-invalid, flamboyantly homosexual Strachey, seventeen years older than herself. The ménage lasted until his death in 1932. Six weeks later she shot herself.

Succeeding eras have imposed radically different perspectives on this elusive, compelling figure, as I find returning to her now. Aldous Huxley, D. H. Lawrence and Rosamond Lehmann all tried to capture her in fiction. In her short lifetime she was patronized by Bloomsbury’s intellectuals as Lytton’s doting cook/housekeeper; Holroyd’s Strachey revealed her strange originality; the feminist 1970s and ’80s redeemed her as a talented artist hampered by the failure of Strachey and Ralph Partridge, who married her, to encourage her as a painter. At last, a wonderful 2013 exhibition of work by Carrington and her contemporaries at the Dulwich Picture Gallery, based on David Boyd Haycock’s book A Crisis of Brilliance (2009), definitively reinstated her as central to an explosion of talent at the Slade School of Art before the Great War.

Today Carrington e

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inOn New Year’s Day 1917 Carrington noted in her diary that her portrait of Lytton Strachey was finished; knowing her achievement, she hugged it to herself. ‘I should like to go on always painting you every week, wasting the afternoon loitering, and never, never, showing you what I paint . . .’ Today her loving tribute is on display in the National Portrait Gallery – an exception for this ambitious yet secretive painter, whose work rarely appears in public collections.

In the tsunami of Bloomsburiana launched by Michael Holroyd’s masterly biography of Strachey (1969), Dora Carrington mostly plays a bit part outside the core group of radical artists and thinkers, through her all-consuming attachment to Strachey, who was at its epicentre. Months after painting his portrait she famously defied her family, besotted suitors and the terrifying consensus of his friends to set up home in the country with the stork-limbed, semi-invalid, flamboyantly homosexual Strachey, seventeen years older than herself. The ménage lasted until his death in 1932. Six weeks later she shot herself. Succeeding eras have imposed radically different perspectives on this elusive, compelling figure, as I find returning to her now. Aldous Huxley, D. H. Lawrence and Rosamond Lehmann all tried to capture her in fiction. In her short lifetime she was patronized by Bloomsbury’s intellectuals as Lytton’s doting cook/housekeeper; Holroyd’s Strachey revealed her strange originality; the feminist 1970s and ’80s redeemed her as a talented artist hampered by the failure of Strachey and Ralph Partridge, who married her, to encourage her as a painter. At last, a wonderful 2013 exhibition of work by Carrington and her contemporaries at the Dulwich Picture Gallery, based on David Boyd Haycock’s book A Crisis of Brilliance (2009), definitively reinstated her as central to an explosion of talent at the Slade School of Art before the Great War. Today Carrington emerges as a curiously modern figure, hard to categorize in what Holroyd calls her catlike ‘solitary and promiscuous nature’, shunning the crowd yet needing people, dedicated to a companion who was effectively out of reach. Snapshots show her pigeon-toed and frowning away from the camera, revealing none of the breathless vivacity that drove gifted young men to distraction. But her childlike ‘quick eager spirit’ fairly leaps off the pages of two books which allow her to speak for herself. She was essentially an autobiographical painter, and Jane Hill’s The Art of Dora Carrington (1994) offers a graphic visual chronicle of the people and places that populated her world. She was also a prolific, funny, impetuous correspondent whose misspelt letters scattered with sketches were, Virginia Woolf told her, ‘completely unlike anything else in the habitable globe’. Her letters and diaries were edited by her friend David Garnett (another suitor) to create a freshly minted, spontaneous account of her life. Carrington’s years at the Slade defined her, as Haycock’s fascinating recent group portrait A Crisis of Brilliance shows. Stanley Spencer, Mark Gertler, Paul Nash and Richard Nevinson were their generation’s YBAs along with Carrington, leader of the ‘crophead’ Slade girls who shed their first names, bobbed their hair and dressed shockingly in loose frocks ‘like nighties’. Gifted, driven, she drew and read obsessively. Her male colleagues and friends admired her; all except Spencer fell in love with her and fell out over her, amid the ferment of ideas following Roger Fry’s post-Impressionist exhibition and competing modernist influences. Carrington rarely signed her work and declared no interest in being ‘a big artist . . . only a creator’; after the Slade she branched out into jobbing work to keep herself afloat. Jane Hill had to search far and wide to gather the scattered evidence of Carrington’s creativity – most surviving paintings are privately owned, her decorative work painted over and lost; but her diligence paid off, capturing the recklessly diverse range of someone for whom artistic expression came as naturally as breathing. Carrington’s pitch-perfect sense of colour, line and form, her wit and lightness make her decorative work pure pleasure for the eye. She loved English popular art and was constantly trying out new media. Inn signs, woodcuts for Leonard and Virginia Woolf ’s Hogarth Press, murals, frescoes, room designs, painted furniture and tiles, tinselled glass pictures – plus countless drawings and doodles strewn over her letters – cascaded from her fertile mind and hand, all distractions from the easel paintings that would have made her reputation. Landscapes meant as much to her as people, painted with passionate concentration and lyrical intensity to create a surreal through-the-looking-glass effect, transporting the viewer into a living pastoral. Tidmarsh Mill has a dreamlike stillness, with its central image of the red-roofed building, the dark tunnel of the mill race flowing beneath and two black swans reflected in the glassy water. David Garnett, editing Carrington’s letters and journals, arranged them so that the drama of her story unfolds like an epistolatory novel, opening – cruelly, given Carrington’s secretive nature – with a letter to Mark Gertler in April 1915 which plunges straight into their ‘sex trouble’. Carrington’s misfortune was to hate being a woman while liking men; both men and women were drawn to her, less by her beauty (she had round cheeks and crooked teeth) than by her intense feeling for it, her radiant energy and quick responsiveness. She and Lytton met in 1915 and were startled by their mutual attraction, though her commitment was always greater; it seems to have been sealed by her brother Teddy’s wartime death in early 1917 when her emotions were rawest. Dreading unanimous disapproval, shrinking from a showdown with the intense, volatile Gertler, she nonetheless secretly imposed her own reality, finding and decorating Tidmarsh (bought by a syndicate of friends) as a haven where she could nurture Lytton. At 38 Lytton too was on a cusp, still without his own home, harassed for his pacifism and unproved as a writer. Eminent Victorians was published in May 1918 (see SF No. 33); his four candid, irreverent brief lives struck a nerve in the battle-weary reading public, exposing the muddle, hypocrisy and complacency that had culminated in the mass slaughter of the Great War. Strachey’s revelations of his illustrious subjects’ private lives stirred up terrific controversy, challenging the conventions of Victorian hagiography and transforming the way public figures would be written about. The book made his reputation and his fortune. From then on his life’s pattern was established: retreating to read and write at Tidmarsh, where Carrington ministered to his every need and entertained their many friends, sallying forth when the country bored him to travel and be lionized. ‘Do you know, I am never so happy as when I paint,’ she wrote to him; yet how many hours did she lavish on Tidmarsh Mill and Ham Spray House, the two homes they shared. Her effects were more delicate, less violently Bohemian than Charleston, with gardens as particular as the décor (a tulip garden, a special lily-of-the-valley bed). Ham Spray’s library had the best views and was a shrine to Lytton. To one visitor, he could have ‘been designed as the perfect objet d’art to go with the background of the house’. Their friends wondered at Carrington’s reverent bondage, ‘in a young woman who in all other respects was fiercely jealous of her independence’. The volume of letters they wrote to each other when apart is astounding. Garnett’s selection gives us only her side of events; this seemed enough when I first fell under the spell of Carrington who, though describing herself as ‘almost entirely visual’ and despite her many other adventures, insisted that Strachey alone made her complete. His chief significance to me then lay in what he meant to her. This time, however, I resorted to Michael Holroyd’s rewritten, shorter Lytton Strachey: The New Biography (1994) to put the man himself and their relationship into three-dimensional context. Whereupon the waspish gossip teased about shawls and Sanatogen in Carrington’s letters zooms into focus as the unnervingly clever private conscience of Bloomsbury, intimate of Woolfs, Bells and Keyneses, Fry and Grant, and their advocate for complete integrity and freedom from prejudice in their personal lives – his very campness and frivolity being part of the subversion. Carrington loved Lytton because he made no demands on her; but she knew that if she clung to him she would lose him. Hence their ‘Triangular Trinity of Happiness’, notably with Ralph Partridge, athletic and practical, who forced Carrington to marry him; and his best friend Gerald Brenan, self-imposed Spanish exile. The tragi-comic liaisons dangereuses would spread like an Iris Murdoch novel on speed: on Carrington’s side always, because of Lytton, doomed to failure, yet because she could never bear to let anyone go, retreating into endless deceptions and prevarications. All Carrington’s letters are infused with her devotion to Lytton, but three especially show the depth of feeling and the lengths to which she would go to keep him. Though intimidated by Virginia and Leonard Woolf, she rounded on them for neglecting Lytton when he was ill. ‘Please write a PC and say when we may expect you,’ she wrote fiercely. ‘And if you dare refuse I shall pray to God to send the shingles upon your heads and I’ll never cut a blasted wood block for you again.’ Her letter to Lytton explaining that she was marrying Ralph so as not to be a burden to him, her ‘Moon’, is beyond sadness. And after Ralph left her for Frances Marshall, the deadly sincerity of Carrington’s plea to Frances to allow Ralph to spend time at Ham Spray, not for herself but because of Lytton’s attachment to him, brooks no refusal. Lucky for them and for us that these two awkward, complicated individuals, at odds with themselves and convention until they found ease with each other, are presented in forms so well suited to them. Carrington, spontaneous and intuitive, springs to life through the medium of her own words and pictures. And there is neat symmetry in the way that the first edition of Holroyd’s biography of Strachey caused shock as widespread, in the ‘emancipated’ climate of the Sixties, as Eminent Victorians had when first published. Holroyd argues convincingly that Lytton proved his thesis, his own sexuality contributing to his subversive stance as a historian: that by debunking idols and exposing their private face he set a precedent which changed the craft of biography. In turn Holroyd’s life of Strachey ushered in the literary biography as a genre, and an era in twentieth-century publishing which only now is evolving again, towards shorter group portraits – as in A Crisis of Brilliance. Plus ça change.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 41 © Anne Boston 2014

About the contributor

Anne Boston is the author of Lesley Blanch: Inner Landscapes, Wilder Shores and editor of Wave Me Goodbye: Stories of the Second World War.