I always take particular pleasure in people’s stories about how they discover books.

For me, the process is quite conventional, more often than not the result of a trip to the London Library, through word of mouth, via Slightly Foxed, or a profitable hour or two spent in a favourite

second-hand bookshop. There is one exception in my experience, though: a discovery made thanks to a devastating fire at a country house.

Around 3.30 p.m. on 30 August 1989, alarms sounded at Uppark, the imposing National Trust property perched high up on the South Downs in West Sussex.

The house, dating back to 1690, was being extensively repaired. Workers welding lead on the roof failed to notice that wooden beams underneath had caught fire. The result was devastating – the blaze ripped through the ancient fabric, destroying the upper floors and everything in them.

Thanks to the quick thinking of shocked National Trust staff and firefighters, a great deal of furniture and other items were saved from the flames. Then debate raged as to whether or not Uppark should be restored to its former glory. In the end the Trust went ahead with the restoration, and the house was reopened to the public in 1995.

Those horrendous images on the television news stayed with me, and, having known the house as it was before the fire, I was determined to see its restoration for myself. On that visit (and I have to say the Trust has done a wonderful job), I bought a copy of Uppark Restored by Christopher Rowell and John Martin Robinson. It carries a foreword by the then Director-General of the National Trust, Martin Drury, which recalls another, fictional house destroyed by fire:

‘Next there came a low rumble, sparks flying like fireworks . . . and the whole of Uptake was roaring and crackling.’ These words described the climax of a story published in 1942, strangely prefiguring the fire that ravaged Uppark forty-five years later. The Last of U

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inI always take particular pleasure in people’s stories about how they discover books.

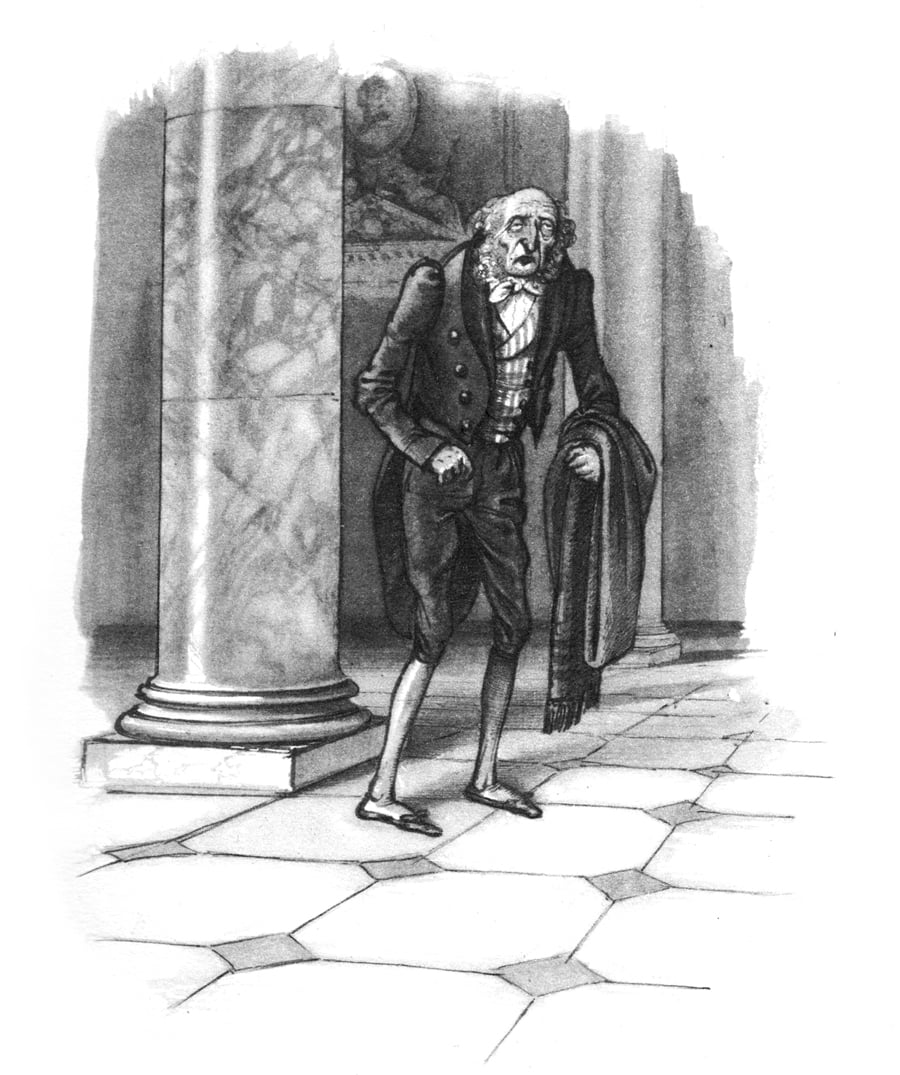

For me, the process is quite conventional, more often than not the result of a trip to the London Library, through word of mouth, via Slightly Foxed, or a profitable hour or two spent in a favourite second-hand bookshop. There is one exception in my experience, though: a discovery made thanks to a devastating fire at a country house. Around 3.30 p.m. on 30 August 1989, alarms sounded at Uppark, the imposing National Trust property perched high up on the South Downs in West Sussex. The house, dating back to 1690, was being extensively repaired. Workers welding lead on the roof failed to notice that wooden beams underneath had caught fire. The result was devastating – the blaze ripped through the ancient fabric, destroying the upper floors and everything in them. Thanks to the quick thinking of shocked National Trust staff and firefighters, a great deal of furniture and other items were saved from the flames. Then debate raged as to whether or not Uppark should be restored to its former glory. In the end the Trust went ahead with the restoration, and the house was reopened to the public in 1995. Those horrendous images on the television news stayed with me, and, having known the house as it was before the fire, I was determined to see its restoration for myself. On that visit (and I have to say the Trust has done a wonderful job), I bought a copy of Uppark Restored by Christopher Rowell and John Martin Robinson. It carries a foreword by the then Director-General of the National Trust, Martin Drury, which recalls another, fictional house destroyed by fire:‘Next there came a low rumble, sparks flying like fireworks . . . and the whole of Uptake was roaring and crackling.’ These words described the climax of a story published in 1942, strangely prefiguring the fire that ravaged Uppark forty-five years later. The Last of Uptake by Simon Harcourt-Smith, with illustrations by Rex Whistler, is a picturesque novel about a country house called Uptake, the home of two old ladies, the last of their line, who set it on fire to prevent it from passing into other hands. Rex Whistler’s tailpiece shows the sisters driving away in their carriages with the great house ablaze in the distance.Uppark, too, was home to two old ladies at the end of the nineteenth century, the owner Miss Fetherstonhaugh and her companion. Miss Fetherstonhaugh bequeathed it to the son of a neighbour, Admiral the Honourable Sir Herbert Meade-Fetherstonhaugh, who inherited it in 1931. He spent the next thirty-five years preserving the house, which later passed to the National Trust. But what of this book, The Last of Uptake, and its Rex Whistler connection? Published by Batsford, it’s a neat, square volume, on that wartime paper that so often yellows appealingly with age and feels almost like felt. The obvious draw is its wonderful illustrations. I always think of Whistler alongside those other distinctive mid-twentieth century giants, Ravilious, Bawden, Laider – better known as the cartoonist, ‘Pont’ – and Ardizzone. Whistler’s work here is simply lovely, bringing house, grounds and characters vividly to life. It does not, however, eclipse Harcourt-Smith’s finely crafted tale of internecine sibling rivalry and creeping decay. Apart from the grim sisters, Lady Tryphena and Lady Deborah, we meet Plummett the housekeeper, Hake the butler, and Titmarsh the gardener. All, of course, are completely devoted to the crumbling sisters and their equally crumbling home. You can almost imagine Hake the butler being covered with a thick layer of dust:

He had come to look very ancient and frail these last years; and he was growing, what one could only call, a little soft in the head; but the other day, hadn’t they caught him, with a gigantic rusty pair of snuffers, trying to snuff the gas lamps in the Chinese saloon?Harcourt-Smith, though quite prolific in his own way, is something of a literary enigma. His voice can be briefly heard thanks to a letter he sent to the TLS in 1953, in defence of his book on the Borgias, The Marriage at Ferrara, in which he hits back forcibly at allegations of plagiarism from a rival historian, but The Last of Uptake is entirely different from the rest of his output, which was scholarly and factual. I want you to read this delightful little book, so no spoilers here, but his scene-setting of Uptake is a delight:

the mist became tangled in the elms, twined under the pediment, set the stucco sweating. Drops of moisture as big as grapes fell and burst on the flags in the colonnade; at times there fell with them bits of swallows’ nests, or the plaster tip of some Emperor’s nose. It all made a terrible mess . . .The grounds are dilapidated, filled with mouldering ornaments, and even some extraordinary automata in various states of collapse, constant reminders of a happy past the sisters can never retrieve. There is a uniquely compelling atmosphere of decline permeating the book. Apart from the fact that it appeared in the dark days of a war (a war that claimed the life of Whistler), the fall of the country house and the ‘servant crisis’ were already well under way by the time it came out. Stately homes were being lost thanks to a combination of genteel poverty, crippling death duties and the dearth of domestic staff; four centuries of architectural heritage were swept away in the space of four decades or so. In publishing terms, The Last of Uptake was also a casualty of war. Rebecca West knew it well and lamented its limited success: ‘The book has long been a treasure of mine, and I have always thought it a great misfortune that it failed to be recognized as a classic because it was published during the war.’ Slim it may be, but this is a neglected volume that will haunt you long after you have put it down.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 68 © Anthony Longden 2020

About the contributor

Journalist and crisis communications specialist Anthony Longden gamely continues to fight a losing battle against the steadily rising tide of books that threatens to engulf his home.