Naturally, any addicted reader’s greatest pleasure is to discover some new book or author – unexpected, sympathetic, in tune with one’s mood. But there are also times when only an old favourite will do, something one can rely on for enthralled contentment. To qualify as an absolutely prime old favourite a book needs particular qualities. It must be capacious enough to immerse the reader completely. The characters must be like old acquaintances, familiar but never absolutely understood, and the events must become almost one’s own memories. The best of such books are always fresh because, as one grows older, they provide new insights and amusements in the light of one’s wider experience of self and others.

My own prime favourite is Anthony Powell’s sequence of novels A Dance to the Music of Time: panoramic, sharply observed, farcical, ironic, yet shot through with what Kingsley Amis called an endlessly inquisitive melancholy. We shadow the narrator Nick Jenkins from the callow half-understanding of youth, in the Twenties, through the drastic remaking of lives and relationships by war, to late middle age in the heady Sixties and Seventies – a whole new age of absurdity against which the novel’s various endgames are played out. We see through Jenkins’s eyes the enormous range of people who make up his life as they diverge and reconnect in new and unexpected, comic or disastrous patterns. In fact A Dance has given a label to that area of experience. When friends from distant corners of our acquaintance unexpectedly marry, or turn out to be old enemies, or otherwise rearrange themselves in new and to us surprising combinations, we often talk of life as being ‘just like Anthony Powell’.

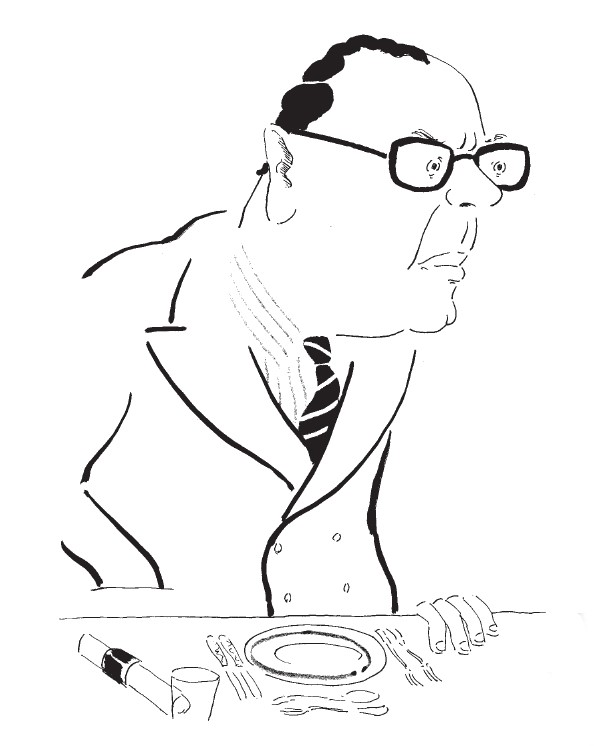

A Dance certainly scores on generosity of scale – fifty or so major characters plus four or five hundred others, well over a million words, twelve volumes covering fifty years (nearer sixty if one counts a substantial flashback). Some people find all this too vast an investment of time and attention. For me though its size just gives it a greater gravitational pull. Every few years my eye will fall on the spines of the Powells on my shelves, and suddenly one of them will be in my hand. I’ll start by looking at one of Mark Boxer’s covers, thinking how extraordinary it is that he imagines Powell’s characters exactly as I do myself. But by the time I’m reflecting on his interpretation of Widmerpool, or Mrs Erdleigh, or Rowland Gwatkin, or X Trapnel, I know I won’t be content until I’ve read the whole sequence again.

A Dance to the Music of Time is immense and many-sided, like life itself, and there is surely no other author of recent times who so brilliantly conveys the sense of life as actually lived – inconsequential and directionless at the time, its underlying

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inNaturally, any addicted reader’s greatest pleasure is to discover some new book or author – unexpected, sympathetic, in tune with one’s mood. But there are also times when only an old favourite will do, something one can rely on for enthralled contentment. To qualify as an absolutely prime old favourite a book needs particular qualities. It must be capacious enough to immerse the reader completely. The characters must be like old acquaintances, familiar but never absolutely understood, and the events must become almost one’s own memories. The best of such books are always fresh because, as one grows older, they provide new insights and amusements in the light of one’s wider experience of self and others.

My own prime favourite is Anthony Powell’s sequence of novels A Dance to the Music of Time: panoramic, sharply observed, farcical, ironic, yet shot through with what Kingsley Amis called an endlessly inquisitive melancholy. We shadow the narrator Nick Jenkins from the callow half-understanding of youth, in the Twenties, through the drastic remaking of lives and relationships by war, to late middle age in the heady Sixties and Seventies – a whole new age of absurdity against which the novel’s various endgames are played out. We see through Jenkins’s eyes the enormous range of people who make up his life as they diverge and reconnect in new and unexpected, comic or disastrous patterns. In fact A Dance has given a label to that area of experience. When friends from distant corners of our acquaintance unexpectedly marry, or turn out to be old enemies, or otherwise rearrange themselves in new and to us surprising combinations, we often talk of life as being ‘just like Anthony Powell’. A Dance certainly scores on generosity of scale – fifty or so major characters plus four or five hundred others, well over a million words, twelve volumes covering fifty years (nearer sixty if one counts a substantial flashback). Some people find all this too vast an investment of time and attention. For me though its size just gives it a greater gravitational pull. Every few years my eye will fall on the spines of the Powells on my shelves, and suddenly one of them will be in my hand. I’ll start by looking at one of Mark Boxer’s covers, thinking how extraordinary it is that he imagines Powell’s characters exactly as I do myself. But by the time I’m reflecting on his interpretation of Widmerpool, or Mrs Erdleigh, or Rowland Gwatkin, or X Trapnel, I know I won’t be content until I’ve read the whole sequence again. A Dance to the Music of Time is immense and many-sided, like life itself, and there is surely no other author of recent times who so brilliantly conveys the sense of life as actually lived – inconsequential and directionless at the time, its underlying pattern emerging only in retrospect. Powell gives us the sense that we are reading something wider and less formed than a novelist’s invention by disguising the books as a long memoir, based on anecdotes – marvellous stories leading from one to another but open to sudden changes of mood as comedy veers towards pain and grief or vice versa. These stories are propelled by some of the most memorable characters in modern literature – eccentric, power-seeking, inadequate, sinister, amusing, charmless, perceptive, wholly lacking in self-knowledge, and sometimes uncannily like one’s friends. Even the most minor are completely realized, the subject of Powell’s full attention, since as Jenkins writes, ‘all human beings, driven as they are at different speeds by the same Furies, are at close range equally extraordinary’. As a novelistic form this seeming memoir is quite original in its untrumpeted way (and incidentally quite unlike A la recherche du temps perdu, with which it is sometimes compared). It gives readers a sense not so much of observing as of taking part. Nick Jenkins’s tone as narrator is conversational, provisional. He seems at times hardly better informed than we are ourselves. In the course of the sequence his take on events is altered, like our own, by what comes to light, or by what others say, or just by growing up. The sense that we are involved with a world not imagined but remembered is deepened as well by the fact that its settings are those of Powell’s own life. Jenkins’s school is clearly Eton, like Powell’s, seen through the unromantic eye of a schoolboy and smelling of blankets and carbolic, Irish stew, laundry baskets and coke fires. The university is Oxford – treated similarly. Castlemallock, where Jenkins spends part of the first half of the war (a ‘sham fortress, monument to a tasteless, half-baked romanticism, becoming now, in truth, a military stronghold, its stone walls and vaulted ceilings echoing at last to the clatter of arms and oaths of soldiery’) and the War Office, where he spends the second half, are based on Powell’s own experiences too. Jenkins’s in-laws have a good deal in common with the Pakenhams, who were Powell’s. Other settings are also shared, from Aldershot to Venice, Cabourg to Bayswater. Yet conversely, using actuality as the scene, having his characters inhabit the same rooms and pavements as ourselves, gives Powell’s inventiveness freedom to roam around the comic, the fantastic, even the grotesque. The matter-of-fact reality of the background intensifies the imagined foreground. An exotic figure like General Conyers, for instance, a brilliantly efficient and ruthless soldier old enough to have taken part in Victorian wars (‘Supposed to have saved the life of some native ruler in a local rumpus. Armed the palace eunuchs with rook rifles’) who now plays the cello and has taken up psychoanalysis, is both more extraordinary and somehow more credible for being planted in Surrey or Knightsbridge. In fact the sober reality of their setting provides a comic foil for the whole range of Powell’s characters, many of them monsters, crackpots, extremes of egotism, and (I notice for the first time, writing this) surprisingly often unorthodox in their sexual tastes – tending to voyeurism, humiliation, cruelty, masochism and necrophilia in one combination or another. Jenkins also resembles Powell in that he becomes an author, pursuing a life of imagination, a spectator of those around him, who are almost always interested in some form – possibly an arcane form – of power. Certainly, few characters in fiction or life pursue power more implacably than Kenneth Widmerpool. Widmerpool is a comic creation bordering on genius, and A Dance opens with him, at school in 1921. He is a little older than Nick Jenkins, and appears through the December fog from a solitary and self-enforced training run, ‘fairly heavily built, thick lips and metal-rimmed spectacles giving his face as usual an aggrieved expression’. Widmerpool at school is hardly more than a joke: unassimilable, comfortless, dogged and inelegant, with a fish-like cast of countenance, thick protesting voice and squeaky boots. In the world beyond school, though, ‘the severe rule of ambition that he [has] from the beginning imposed upon himself: the determination that existence must be governed by the will’ soon start to make him a considerable figure. He loses none of his social indigestibility – Jenkins observes him at the Huntercombes’ ball ‘ploughing his way round the room, as if rowing a dinghy in rough water’ – but other school contemporaries, now business associates, start to set store by his effectiveness rather than his oddity. More than ever like a fish, he now has something frightening about him too. Nor do personal setbacks interrupt his rise. Sent packing for impotence by his louche and unsuitable fiancée Mildred Blaides, he is soon congratulating himself on his wisdom in breaking off his engagement, and pressing on Jenkins his views concerning marriage. During the war, Jenkins comes across him again, in his top-secret office – in fact a stuffy back room in his old territorial HQ – and cannot escape being selected as the best of a bad bunch of candidates for the post of his junior assistant. ‘Widmerpool’s view of himself as a man handling weighty state secrets was beyond belief in its absurdity.’ Nonetheless in due course he is working with the War Cabinet, promoted colonel, awarded an OBE. After the war he rises to still loftier heights and new forms of grating self-aggrandizement – a peerage, and the chancellorship of some new university – before his lurid end. In the course of A Dance Widmerpool becomes in Jenkins’s mind ‘one of those fabulous monsters that haunt the recesses of the individual imagination’. He also becomes one of the most potent comic figures of literature. Like Falstaff he seems to have detached himself from his author’s mind and reappeared in our own experience: most of us feel we have a Widmerpool figure in our lives, someone who reappears unwelcomely at intervals and annoys us by disparaging our choices in life without noticing our values and concerns or their possible difference from his own. Also in Jenkins’s house at school is Charles Stringham, as unlike Widmerpool as could be conceived. ‘He was tall and dark, and looked a little like one of those stiff, sad young men in ruffs, whose long legs take up so much room in sixteenth-century portraits . . . His features certainly seemed to belong to that epoch of painting: the faces in Elizabethan miniatures, lively, obstinate, generous, not very happy, and quite relentless.’ At school Stringham is richer and more sophisticated than the others and has an unforced elegance, charm and wit. He is a mimic noted for his ‘ludicrously exact’ imitations of Widmerpool, and is briefly high-spirited enough to arrange as a practical joke for his housemaster’s arrest by the police. Nonetheless, melancholy is already diminishing him. Exile by his mother and stepfather – the Gertrude and Claudius of his life – then a failed marriage, then alcoholism, lead to forced confinement by his sister’s ex-governess, who was once in love with him and now keeps him to a teetotal regime, reading Browning and painting in gouache. Stringham lacks Widmerpool’s drive to power and becomes the sardonic observer of his own strange and unsatisfactory life, as entertained by failure as by success. This is not a recipe for advancement. It’s a chilling moment when Jenkins, dining gloomily in the officers’ mess at Divisional HQ in 1941, realizes that the arm of the new mess waiter over his shoulder is Stringham’s. ‘Between you and me, Nick, I think I have it in me to make a first class mess waiter. The talent is there. It’s just a question of developing latent ability.’ Stringham’s appearance produces some particularly delicious odiousness from Widmerpool: ‘War is a great opportunity for everyone to find his own level. I am a major – you are a second lieutenant – he is a private.’ And indeed Widmerpool moves quickly to transfer Stringham to a mobile laundry unit which is on the point of leaving for doomed Singapore – the gorgeous East in Stringham’s ironic phrase. Widmerpool is unmoved by Jenkins’s attempt to prevent this posting, but then so too is Stringham. ‘Awfully chic to be killed,’ he says. His irony and comic self-deprecation now collude in his end. There are far more characters in A Dance than can be introduced, however briefly; nor do I want to give away too much to those who have yet to read the sequence. But life would be the poorer for not knowing, for instance, the clairvoyant Mrs Erdleigh – ‘largely built, dark red hair, huge liquid eyes and rapturous smile’, who ‘seems to glide rather than walk across the carpet’. ‘Lady Warminster was a woman among women,’ she says at one point. ‘I shall never forget her gratitude when I revealed to her that Tuesday was the best day for the operation of revenge.’ Or Dr Trelawney, the seer and charlatan first met running across the heath at the head of a troop of disciples in search of Oneness, a man who is said to have enjoyed the favours of succubi on the Astral Plane and whose prophecies of death and destruction – when the sword of Mithras shall flash from its scabbard, and the slayer of Osiris once more demand his grievous tribute of blood – are uncomfortably correct. Or Dicky Umphraville, womanizer and according to himself professional cad, about whom ‘there was a suggestion of madness . . . not the sort of madness that was raving, or even, in the ordinary sense, dangerous; but a warning that no proper mechanism existed for operating normal controls’. Or above all the coldly magnetic Pamela Flitton, whose specialism is the offhand degradation of men – any men. ‘She appeared . . . scarcely at all interested in looks or money, rank or youth, as such; just as happy deranging the modest home life of a middle-aged airraid warden as compromising the commission of a rich and handsome Guards ensign recently left school.’ Her catastrophic effect on no fewer than three major characters almost simultaneously is one of the dramatic denouements at the end of the sequence. Since Powell set A Dance so much in his own haunts, finding reallife originals for his characters was a literary game for years. Powell himself had views on how far one could use living people in fiction, and which living people might suit. He wrote tetchily of his brother-in-law Lord Longford, who was keen on taking part: ‘It is characteristic of people who know nothing whatever of novel writing to suppose that only someone with a recognizable newspaper persona would make a good character. In point of fact I cannot imagine even considering Frank as a model . . . Frank uses up all his own “image” in publicity, leaving nothing in suspension, something essential in creating a novel-character based in real life . . .’ Powell was prepared to allow that there are some characters whose provenance is not really in doubt. Stringham owes a lot to Curzon’s nephew Hubert Duggan; the composer Hugh Moreland is based on Constant Lambert; X Trapnel has a good deal in common with Julian Maclaren-Ross. But the most developed characters, if they were to live on the page, had to be drawn from some hidden wellspring of creativity – so well hidden in fact that Powell himself could join in speculating about their origins. Barbara Skelton, wife of first Cyril Connolly and later Lord Weidenfeld, was certainly a model for Pamela Flitton, he thought, at any rate in her ‘complete disregard for what anyone might think of her’ and in ‘making no bones about causing trouble for its own sake’. George Orwell’s wife Sonia too, he agreed, was a likeness, though it had not occurred to him at the time of writing. Surprisingly, some people actually wanted to be his originals. The novelist Henry Yorke put it about that he was Stringham, though as Powell said it would be hard to imagine anyone less like him. Tom Pakenham said his father Lord Longford, in a single letter, claimed at one point to be Erridge (Jenkins’s brother-in-law) and at another to be Widmerpool. Powell did not have much sympathy with this. Really, he said, he could not be everyone in the novel. Widmerpool was certainly the character who collected the most candidates. Others proposed for him include Tom Driberg (‘Labour MP and insatiate homosexual’), Reginald Manningham-Buller (tyrannical civil servant), Denis Capel-Dunn (‘loudmouth barrister’) and (this one a suggestion of Denis Healey’s, surprising even to Powell) Ted Heath. I wrote earlier that A Dance was constructed as a memoir, and indeed it is. But at a level below the anecdotal it has a complex structure, for instance in the way regroupings of characters, often surprising at the time, bring to light different facets of personality and by doing so push the action onwards. Rereadings – this is one reason why rereadings are so much fun – also constantly point up patterns, resonances and circularities connecting characters and events at remote parts of the sequence. This is after all a Dance, and dances are by their nature circular and repetitive. Perhaps the clearest instance is Widmerpool’s appearance at the beginning and end, both times running, both times among people who will never accept him, both times chasing a success that his will and drive to power cannot deliver. Connections like these of course give the sequence a subliminal unity, and are part of what make an enormous work aesthetically such a triumph. There is – at any rate I think there is – a related point. Our own lives are apt to feel formless and undirected as we live them; that is part of the human condition. To read a long work like A Dance to the Music of Time, which deals with whole lives, and find that formless and undirected too, at first, but on closer acquaintance imbued with pattern and significance, is in a curious way satisfying, in the way that myth is satisfying. It’s another of the pleasures the sequence can offer, not simply aesthetic but somehow consoling as well.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 16 © Grant McIntyre 2007 Illustration by Mark Boxer

About the contributor

Grant McIntyre was for many years a publisher, most recently editorial director of John Murray. He has now abandoned all that and become a sculptor.