I first heard the name of John Betjeman at university. One of the more adventurous dons, an aesthetically aware mathematician, lent me a copy of Collected Poems (1958), just out. Torn from my Donne, I read:

Kirkby with Muckby-cum-Sparrowby-cum-Spinx

Is down a long lane in the county of Lincs,

And often on Wednesdays, well-harnessed and spruce,

I would drive into Wiss over Winderby Sluice.

‘Call this poetry!’ I said indignantly (it wasn’t the first time I was found too solemn, early in life). Years later I discovered that around the time I was delivering that judgement, Betjeman’s Collected Poems was selling a thousand copies a day – third on the bestseller list. (‘What ho!’ its jubilant publisher Jock Murray is said to have exclaimed, ‘I never remember such a dance since we published Byron’s Childe Harold in 1812.’)

Once I’d finished university I came to enjoy life more – including Betjeman’s poems. Now living, more or less, in the real world, I realized that the most original poetry isn’t usually a matter of intellectual constructions and conceits, but rather of finding expression for thoughts and states of mind in language close to how people speak. This Betjeman does to perfection. And he addresses the world we know. His currency is re

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inI first heard the name of John Betjeman at university. One of the more adventurous dons, an aesthetically aware mathematician, lent me a copy of Collected Poems (1958), just out. Torn from my Donne, I read:

‘Call this poetry!’ I said indignantly (it wasn’t the first time I was found too solemn, early in life). Years later I discovered that around the time I was delivering that judgement, Betjeman’s Collected Poems was selling a thousand copies a day – third on the bestseller list. (‘What ho!’ its jubilant publisher Jock Murray is said to have exclaimed, ‘I never remember such a dance since we published Byron’s Childe Harold in 1812.’) Once I’d finished university I came to enjoy life more – including Betjeman’s poems. Now living, more or less, in the real world, I realized that the most original poetry isn’t usually a matter of intellectual constructions and conceits, but rather of finding expression for thoughts and states of mind in language close to how people speak. This Betjeman does to perfection. And he addresses the world we know. His currency is real named places, English villages and churches with their bells, London suburbs, seaside holidays, train journeys – the paraphernalia of English middle-class life during most of the twentieth century, all viewed through an irresistible lens of affectionate wit and nostalgia. How perfectly he captures the English middle-class psyche in ‘In Westminster Abbey’ (1940), in which a well-dressed lady addresses the Almighty as she kneels and removes her glove:Kirkby with Muckby-cum-Sparrowby-cum-Spinx Is down a long lane in the county of Lincs, And often on Wednesdays, well-harnessed and spruce, I would drive into Wiss over Winderby Sluice.

But with his verse autobiography Betjeman does something different. Summoned by Bells is an account, in blank verse, of his life up to the age of 22 – or the bits of it uppermost in his mind when he was writing it between the ages of around 34 to 54. He says in an initial note to the reader that he wanted to go ‘as near prose as he dare’, and chose blank verse because he found it best suited to ‘brevity and the rapid changes of mood and subject’. I think the word ‘brevity’ here is a piece of shorthand, the lid on a cauldron of emotions and deeply held values, meaning that he could not have expressed what he had to say nearly so spontaneously and truly in either of the more restrictive media of prose or rhymed verse. And of course, ‘blank verse’, unrhymed pentameters, is a typically English understated term, being a favourite vehicle of our greatest poets. In Summoned by Bells we are online to Betjeman’s soul. As usual when a writer does something different, there’s a negative reaction. Leading critics found Summoned by Bells, published in 1960, two years after the Collected Poems, too unintellectual, and the public on the whole stuck to the fizzier, more pointed short poems. To this day it is still overshadowed by them, but I fell in love with it as soon as I read its magical opening lines – I can’t remember exactly when, but my copy I see is the 1976 edition:Gracious Lord, oh bomb the Germans, Spare their women for Thy Sake, And if that is not too easy We will pardon Thy Mistake. But, gracious Lord, whate’er shall be, Don’t let anyone bomb me . . .

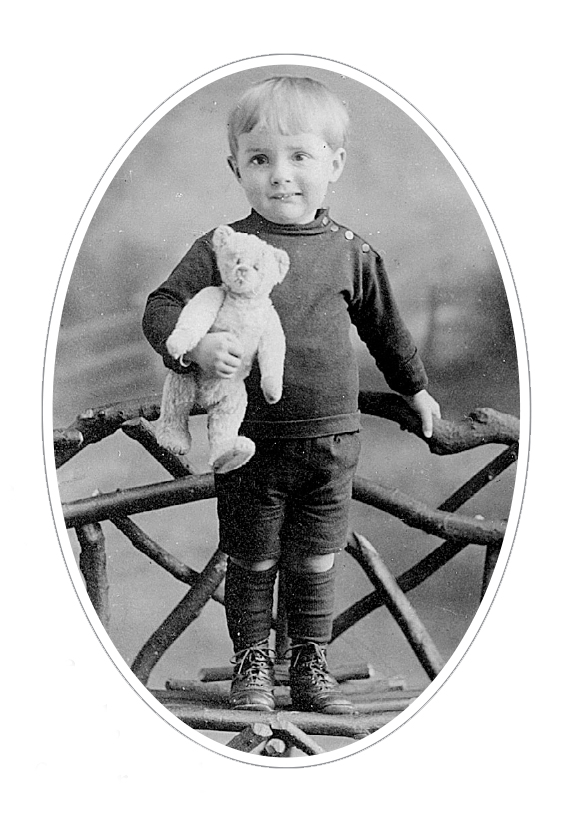

This was familiar ground. For a short while my parental home had been a little further up West Hill from No. 31, the house of Betjeman’s boyhood. And cross-country running at Highgate School, where Betjeman spent two unhappy years, I and the rest of the pack had put many a blackbird to flight over those miles of Hampstead Heath. I have to say there’s nothing like a topographical link with an author to give one an insider tingle. Betjeman’s fond reference to places is a very real part of his appeal: Egloskerry, Tresmeer, Trebetherick – even though I don’t know them, I enjoy hearing their names and imagining them. Betjeman once replied to someone who had called him ‘a poet of place’ that it wasn’t really the places that drew him, it was the people in them. And in this first chapter the person who stands out unforgettably is his ‘first and purest love’ at the age of 8, a fellow pupil at his Montessori school with ‘ice-blue eyes’ and ‘lashes long and light’, Peggy Pury-Cust. Betjeman’s personal names too are an unforgettable part of his poetry – think of Miss Joan Hunter Dunn. John Betjeman himself was the only surviving child of a manufacturer of furniture and household articles (the firm made its fortune in the mid-Victorian era with the Tantalus – a device for locking away decanters of drink from servants) who represented the third generation of a company founded in 1820 and which continued in business until 1945. Here is one of the many evocative passages in Summoned by Bells in which the past leaps up before us. Master John, aged 7 or 8, is being proudly taken round the Betjeman manufactory located next to the Angel, Islington, on the eve of the Great War by his father and introduced to the operatives and craftsmen:Here on the southern slope of Highgate Hill Red squirrels leap the hornbeams. Still I see Twigs and serrated leaves against the sky. The sunny silence was of Middlesex. Once a Delaunay-Belleville crawling up West Hill in bottom gear made such a noise As drew me from my dream-world out to watch That early motor-car attempt the steep. But mostly it was footsteps, rustling leaves, And blackbirds fluting over miles of Heath.

But John was determined not to be a fourth-generation manufacturer. He knew ‘as soon as he could read or write’, he tells us, that he must be a poet. Arising from this, guilt is a dominant theme of Summoned by Bells. At various moments of his narrative he recalls his distraught father, hoping against hope that his son will continue the family firm. Handling a newly published volume of his own verse, he sees in his mind’s eye his father’sThe cabinet-makers’ shop, all belts and wheels And whining saws, would thrill me with the scream Of tortured wood, starting a blackened plank Under the cruel plane and coming out Sweet-scented, pink and smooth and richly grained; While in a far-off shed, caressingly, French-polishers, all whistling different tunes, With reeking swabs would rub the coloured woods . . .

Physical beatings and moral humiliations recur: ‘that awful feeling, fear confused with thrill’ as, late for dinner again, he is unbuttoned and bent across Nanny Maud’s starchy apron; he is punched and kicked in the street by fellow schoolboys, while others jibe, ‘Betjeman’s a German spy – Shoot him down and let him die’; at prep school in Oxford he receives a resounding three from, in fact, a favourite master (‘I liked the way you took that beating, John./Reckon yourself henceforth a gentleman’). At Highgate Junior School, his first attempts at serious verse are coolly received by ‘the American Master’, T. S. Eliot, and during one holiday in Cornwall, a woman in ‘Girl-Guide-y sort of clothes’, who is organizing a children’s event, calls him ‘a common little boy’. But all this is, as it were, subplot. His main theme is the growth of his two great enthusiasms – poetry and England’s architectural heritage. He shows his first verse to his father at the age of 8. At the age of 12, at the Dragon School in Oxford, he takes off on many a blissful bike expedition in and outside the city to inspect the ‘Norm., E.E., Dec.’ and ‘lamentable Perp.’ churches of the area,often in the company of a master who shares his passion. His verse breathlessly catches his excitement as he hunts down the keys of locked-up churches to discover ‘vaulting shafts,/Pillar piscinas, floriated caps.,/Squints, squinches, low side windows, quoins and groins . . .’ On winter Sunday evenings during Christmas school holidays, the prep-school boy would stand at lane intersections among the silent office buildings in the City and listen – not for an active or familiar peal, as from St Paul’s, but for the sound of an occasional, barely active bell, likely to be that of a church whose statutory service was being taken by ‘some lazy Rector living in Bexhill’, with scarcely any congregation, where he could enjoy 300-year-old interiors, hear the Book of Common Prayer and appease his already mounting sense of guilt in peace. Summoned by Bells is rich in such unexpected intimate moments which point forward to the time when the ugly duckling would turn into a swan – the hugely popular architectural writer, broadcaster and conservationist. It was at the Dragon School, too, that the nature of his ‘Faith’ was established for the rest of his life, as he recalls in describing his time as an Oxford undergraduate:. . . workmen seeking other jobs, And that red granite obelisk that marks The family grave in Highgate Cemetery Points an accusing finger to the sky.

As at the Dragon School, so still for me The steps to truth were made by sculptured stone, Stained glass and vestments, holy-water stoups, Incense and crossings of myself – the things That hearty middle-stumpers most despise As ‘all the inessentials of the Faith’.This is the heart of Betjeman. Those critics who dismissed him as a poet were at least right in this respect – he is no intellectual. He deals in the concrete, not in ideas. It was the 8-year-old’s urge ‘to encase in rhythm and rhyme/The things I saw and felt (I could not think)’ that was to make him Poet Laureate. Summoned by Bells has plenty that he saw and felt. The episode on a Cornish family holiday – when his father tells him to make himself useful instead of lounging about the house: (‘I’ll have obedience!’) and his son replies ‘You damn well won’t’ and makes for the door and his bike – brought a rush of blood to my head as I remembered similar scenes from my own adolescence. Without rhyme, Betjeman is freed from the pressure to be constantly satirical and jokey, a mode he keeps up so brilliantly in his short rhymed poems. He was worried about the final chapter of Summoned by Bells on his time as an undergraduate at Oxford, fearing that the reader might by then have become bored with unalleviated blank verse, so he interjected some rhymed jingles and one magnificent rhymed poem, which is an ode to Oxford of the Twenties, where ‘life was luncheons, luncheons all the way’.

But he really needn’t have worried. His blank verse is always wonderfully eloquent, sometimes as deeply serious as his fundamentally light-hearted nature will allow, sometimes extremely funny. The Oxford chapter is a brilliant finale, switching from agonized thoughts about his pained parents and the existence of God to memorable exchanges among his circle of close friends which included such notables and eccentrics as Harold Acton, Maurice Bowra, Osbert Lancaster and Edward James, future patron of Magritte and Dalí.

It was hardly surprising – considering how outrageously young Betjeman seems to have neglected his studies – that he failed his exams and was sent down without a degree. It was at Oxford, nevertheless, that he truly found himself:

I learned . . . . . . that wisdom was Not memory-tests (as I had long supposed), Not ‘first-class brains’ and swotting for exams, But humble love for what we sought and knew.

That insight was to serve him for the rest of his life, and what better text for us in our struggle against the twenty-first century’s obsession with time management, targets and places in the league-tables?

So how sad it is that this great, dear book has been so consistently overshadowed by the shorter poems and that it has been tacked on at the end of an unwieldy edition of the Collected Poems (2006) rather than breathing freely as the independent volume it naturally is. However, I feel I can confidently say that anyone who enjoys the Englishness of English verse, anyone with a taste for autobiography in whatever guise – even those who normally avoid poetry – will find it irresistible.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 28 © Antony Wood 2010

About the contributor

Antony Wood lives in Highbury, North London, where Betjeman’s parents grew up and were married, and from where he runs his publishing firm, Angel Books, devoted to translations of classic foreign authors.