Time is linear. One thing happens, then another, then another. But while time itself may be linear, our memory of it is not. Of course we can order our memories in a linear, sort-by-date, fashion, but we can also sort by importance, by emotion and even (speaking as someone who grew up in the 1970s) by dodgy haircut. And since you are reading a literary magazine you, like me, can probably sort your memories by books – you can pick a book from your bookshelves, start to browse, and be magically transported not only to the world within the book, but also to the world you were living in when you first read it.

I first encountered Denys Watkins-Pitchford, who wrote under the pseudonym of BB, when I was a short-trousered 10-year-old on a fortnightly trip to the library at the top of my road. As I scanned the shelves my eyes were drawn to a book called Down the Bright Stream, not because of the title, but the author. And that was because he didn’t have a name – just those two initials. So I opened the book and found myself in the world of the last gnomes left living in England. I took the book home and dived in. Then I went back to the library and got out The Little Grey Men – the book I should have read first as it was the one that introduced Dodder, Sneezewort, Cloudberry and Baldmoney to the wider world.

Their own world was a small place. It was limited to the woods that surrounded the banks of Folly Brook. Their adventures, too, were miniature affairs. But I was mesmerized by them. And I love these small, fallible heroes who, though recognizably human in character, were creatures in tune with the natural world around them.

Looking back, it’s c

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inTime is linear. One thing happens, then another, then another. But while time itself may be linear, our memory of it is not. Of course we can order our memories in a linear, sort-by-date, fashion, but we can also sort by importance, by emotion and even (speaking as someone who grew up in the 1970s) by dodgy haircut. And since you are reading a literary magazine you, like me, can probably sort your memories by books – you can pick a book from your bookshelves, start to browse, and be magically transported not only to the world within the book, but also to the world you were living in when you first read it.

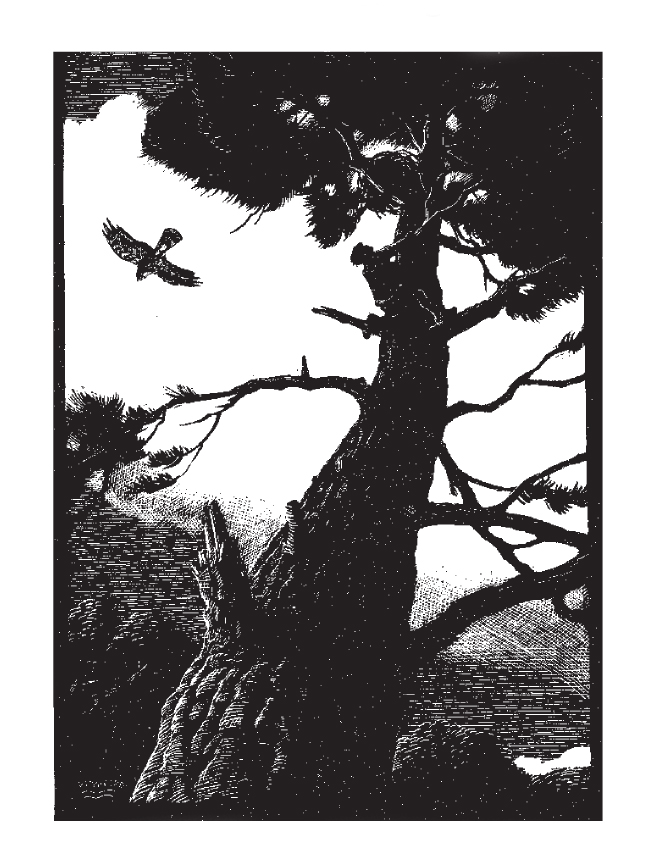

I first encountered Denys Watkins-Pitchford, who wrote under the pseudonym of BB, when I was a short-trousered 10-year-old on a fortnightly trip to the library at the top of my road. As I scanned the shelves my eyes were drawn to a book called Down the Bright Stream, not because of the title, but the author. And that was because he didn’t have a name – just those two initials. So I opened the book and found myself in the world of the last gnomes left living in England. I took the book home and dived in. Then I went back to the library and got out The Little Grey Men – the book I should have read first as it was the one that introduced Dodder, Sneezewort, Cloudberry and Baldmoney to the wider world. Their own world was a small place. It was limited to the woods that surrounded the banks of Folly Brook. Their adventures, too, were miniature affairs. But I was mesmerized by them. And I love these small, fallible heroes who, though recognizably human in character, were creatures in tune with the natural world around them. Looking back, it’s clear to me now that part of the attraction of these books was that although I had been born, bred and buttered in Britain, I was a child of immigrant parents, brought up in inner-city London. For me the countryside was no more than a rumour, or a vision glimpsed fleetingly from the train. But here it was, in these books, and it was magical. Almost forty years on from that first enchantment I read the books again to my son. And he too enjoyed them. This time around I’d bought the books rather than borrowed them, and I also bought a third book by BB, Brendon Chase. The latter too is wonderful. Reading it made me feel like a kid again. A far braver, more resilient and more capable kid than I ever was, but a kid nonetheless. The story concerns three brothers. Robin is 15, John 13 and Harold 12. They live in the Dower House with their maiden aunt on account of their ‘people’ being in India. The story is set in that odd lull in British twentieth-century history that lies in bed refusing to get up, between the two World Wars. It starts as the last day of the Easter holidays looms and the boys face the imminent prospect of a return to their public school – a place of ‘well-pressed trousers, speckled straw hats and black tailed coats’. Three pages in, Robin unveils his plan. ‘My idea is that we should run away to Brendon Chase.’ It is a plan that Robin has obviously thought through with all the rigour of a 15-year-old, as his next line is, ‘Why shouldn’t we live in the forest like Robin Hood and his merry men?’ Gloriously, over the course of the next 300 pages, this is exactly what they do. The plan suffers a slight setback when Harold, the youngest, contracts measles and all three are quarantined. But after a brief prevarication the older boys make a break for it one night, taking what provisions they can muster from the kitchen. They also ‘borrow’ Rumbold the gardener’s .22 rifle and two boxes of cartridges. Ever the considerate nephews, the self-styled ‘Robin (Hood)’ and ‘John (Big)’ leave a note for their aunt that ends ‘Don’t try to find us because you never will.’ Should any modern reader be of a squeamish, namby-pamby, vegetarianish disposition, the presence of the gun should forewarn them that these outlaws intend to live off the land, hunting, shooting, fishing and even raiding birds’ nests for eggs. And of course if you shoot a rabbit, naturally before you can cook and eat it, you have to gut it. To anyone used to meat that comes ready-jointed, chilled and shrink-wrapped in cellophane, this book is a revelation. But that is just one of the things that makes it such a joy. For me, reading the book sixty-five years after it was first published, what it communicates most clearly, once one looks beneath the Boys’ Own adventure of the narrative, is a love of nature and a deep-rooted respect for, and admiration and understanding of the woods, the wildlife and the changing seasons. The fact that the boys have to hunt and kill and gut to survive doesn’t contradict this respect but confirms it. By Chapter 3 the boys have holed up in the still living shell of an ancient oak whose hollowed-out trunk is wide enough ‘to hold 12 fully grown men standing upright’. That same chapter also reveals where BB drew some of the inspiration for Brendon Chase. As night falls, and owls start to hoot, Robin remembers the book he had recently been reading – Thoreau’s Life in the Woods, some passages of which he knows by heart. BB goes on to conjure up the spirit of Thoreau’s Walden Pond and suggest that there exists a similar idyll in Brendon Chase: ‘perhaps the Blind Pool was just such another Walden Pond, a clear deep dish of translucent water set down in the heart of this English forest’. Sixty pages on Robin, hunting alone, finds the Blind Pool and it exceeds all expectations: ‘Some things we see pass out of the mind, or, at least, are forgotten; others, little things, little glimpses such as this never depart. And the memory of that first view of the Blind Pool would still be in his mind forty years afterwards.’ By now you may be thinking that Brendon Chase is fundamentally a philosophical meditation on the nature of Nature and our place in it. Perhaps it is, but it’s also a cracking yarn. You read on wanting to know what happens next, how the boys will survive, and how it will all end. As with all great yarns, a lot of stuff happens. The two older boys return to the Dower House and spring their incarcerated brother from his solitary confinement. A foraging pig is shot, then jointed, salted and smoked. A beehive gets ‘taken’. A dizzying skyscraper of a fir tree is scaled so that a honey buzzard’s nest can be raided. A dog is rescued. A friend is made of an old charcoal-burner. A hunt marshalled by the local squire is evaded. A policeman’s trousers are stolen, a picnic raided. And a horse and cart are hijacked while chase is given by a hardware van, a farmer’s gig and the Duke of Brendon’s magnificent Rolls-Royce. Towards the end of the adventure a life is even saved. Throughout the book BB’s own black-and-white illustrations add an extra dimension to the tale. To my eye the full-page pictures seem dark and brooding, but the smaller images that accompany the start of each chapter have a stark simplicity that adds weight to the story while acting as a visual shorthand for the action that is about to take place. And like all good illustrations they help vary the texture of the book in a way that enhances the written word immeasurably. Of course the boys’ escapade can’t go on for ever. As autumn drifts towards winter the three desperadoes realize that they will have to return home. But they have no regrets. ‘To these three boys had come the opportunity to live that wild savage existence for a while. They had seized it rightly or wrongly, damning the consequences.’ BB’s regrets are far easier to divine. After a passage detailing the wonder of snow and ice on the trees of Brendon Chase he laments:Yet men did not trouble about this beauty, not a soul thought it worth while to venture into the cold, silent Chase. Why should they? There was nothing to see there but endless aisles of oak, twisting ridings, and knee high drifts which made progress wearisome. Those folks with town minds would be acutely unhappy in the Chase, just as the outlaws would have almost expired if they had found themselves transported to the middle of a great city, with brilliant shops all about them and the din of wheels in their ears.Brendon Chase is a gripping, ripping adventure yarn, but it is also a paean to the natural world, infused with a sense of innocence but imbued with yearning regret for things we have lost. Then, browsing through a biography of BB, I discovered that Denys Watkins-Pitchford taught Art at Rugby School and that his son, Robin, died when he was 7. And suddenly a book that Philip Pullman has described as ‘brimming with delight’ took on a whole new meaning.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 25 © Rohan Candappa 2010

About the contributor

Rohan Candappa has written 16 mainly humorous books.