The summer of 2018 was a glory – as long as you weren’t a gardener. For those of us who fret about plants, it was a season as much to be endured as enjoyed. After a cold, late spring, the weather had pulled a U-turn, swerving into an intense dry heat that lasted from June to the end of August. With 7 per cent less rain than even the summer of ’76 – still, after a whole series of climatic upheavals, the touchstone for freak British weather – it wasn’t so surprising that anything newly planted shrivelled in the furnace. More shocking was the number of weighty, established plants that turned their faces to the wall. In my garden in Sussex we lost shrubs and trees that had been happy and healthy for twenty years: Korean lilac, a beautiful Exochorda x macrantha ‘The Bride’, pompom willows, a huge evergreen elaeagnus. Clumps of tickweed flopped; what should have been giant angelica, sown in hope a year before, couldn’t drag itself higher than a few inches off the ground.

Sadly, the Englishwoman best placed to cope with and comment on conditions like these wasn’t around to see them. Beth Chatto, gardener, writer and popularizer of the motto ‘the right plant in the right place’, had died that May, at the excellent age of 94. Regardless of both the weather and Chatto’s departure, her famous garden and its associated nursery bloomed on. As you would expect: its creator wrote what has been for four decades the go-to text for anyone who knows what it is to look at the sky and pray for a drop of rain.

The Dry Garden, Chatto’s first book, was published in 1978, two years after that earlier record-breaking summer. It offered gardeners who’d come to hate the sight of a hose 180-odd pages of drought-be

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inThe summer of 2018 was a glory – as long as you weren’t a gardener. For those of us who fret about plants, it was a season as much to be endured as enjoyed. After a cold, late spring, the weather had pulled a U-turn, swerving into an intense dry heat that lasted from June to the end of August. With 7 per cent less rain than even the summer of ’76 – still, after a whole series of climatic upheavals, the touchstone for freak British weather – it wasn’t so surprising that anything newly planted shrivelled in the furnace. More shocking was the number of weighty, established plants that turned their faces to the wall. In my garden in Sussex we lost shrubs and trees that had been happy and healthy for twenty years: Korean lilac, a beautiful Exochorda x macrantha ‘The Bride’, pompom willows, a huge evergreen elaeagnus. Clumps of tickweed flopped; what should have been giant angelica, sown in hope a year before, couldn’t drag itself higher than a few inches off the ground.

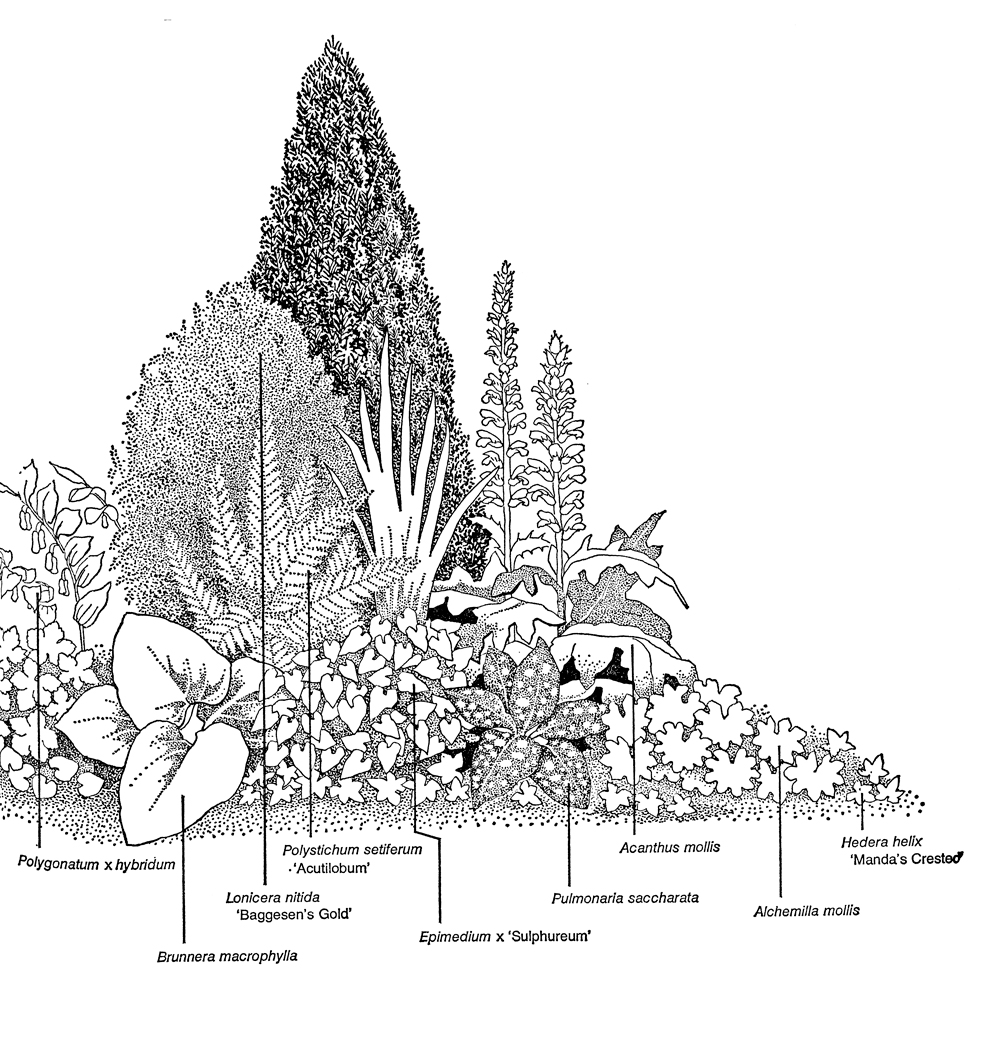

Sadly, the Englishwoman best placed to cope with and comment on conditions like these wasn’t around to see them. Beth Chatto, gardener, writer and popularizer of the motto ‘the right plant in the right place’, had died that May, at the excellent age of 94. Regardless of both the weather and Chatto’s departure, her famous garden and its associated nursery bloomed on. As you would expect: its creator wrote what has been for four decades the go-to text for anyone who knows what it is to look at the sky and pray for a drop of rain. The Dry Garden, Chatto’s first book, was published in 1978, two years after that earlier record-breaking summer. It offered gardeners who’d come to hate the sight of a hose 180-odd pages of drought-beating design, planting and maintenance advice. Crucially, this was based on experience hard-won after what was then already nearly forty years of nurturing plants in East Anglia, England’s driest corner. Within two years the book had been reprinted, and it went on appearing in regular reissues and revisions until the late 1990s, when other, showier garden writers moved centre-stage. Then in 2018 Weidenfeld & Nicolson published the first new edition in twenty years – just as the weather, finally, broke. A case, you might say, of the right book at the right time. It was as much fashion as timeliness that made The Dry Garden a success. Chatto had spent the 1950s teaching flower-arranging, was close friends with a local grandee artist and plantsman, Sir Cedric Morris, and was married to an amateur but passionate botanist. All of which had helped form her particular gardening style. She laid out beds with an aristocratically generous sense of space; planted them with a florist’s knack for first setting up a geometry, then breaking it (she was particularly fond of arranging plants in three-dimensional, interlocking triangles); and used an enormous range of what were then often unfamiliar shrubs and perennials. The results were flowing, rhythmical and always at home in their space: a good fit for the new wave of naturalistic gardening that was sluicing away the prim rockeries and garish bedding of the 1960s. Chatto’s insistence on matching plants to the conditions that best suited them also chimed with more nature-friendly times: the Soil Association, the charity devoted to promoting organic farming and gardening, had been launched just five years previously. Meanwhile her European travels with that botanizing husband, observing plants in unforgiving habitats like the sunbaked, stony hillsides of southern France, meant she properly understood what they needed to thrive. As a nurserywoman she was always assiduous in searching out, growing and recommending new plants that would cope with, even revel in, the most difficult of conditions. Gardeners came to love and rely on her because what she said worked, and her ‘right plant for the right place’ mantra became so widely adopted it’s now a cliché. Like all commonplaces, it’s a pearl of wisdom laid around a central grit of truth. One of the first but sometimes hardest lessons for beginner gardeners is that fighting Nature is a losing game: trying to keep a moisture-loving plant alive in arid soils is both back- and heart-breaking. Chatto’s lifelong focus on the botany of the plants she grew meant she could avoid this kind of unnecessary pain and teach her readers how to avoid it too. Even in the slow-moving world of horticulture, forty years is a long time: our tastes in gardens, and in books, have moved on. Contemporary gardening titles tend to be big on visuals, light on actual advice. That is not the Chatto way. The Dry Garden is a plain child. Illustrations are confined to hand-drawn ground plans, a few marginally more elegant black-and-white line drawings, and a handful of unenlightening monochrome photos, mostly close-ups of plants Chatto particularly valued. In his introduction to the new edition of The Dry Garden, the writer and broadcaster Monty Don says: ‘at a time when gardening could sometimes seem to be a cross between an exercise in good taste and Latin O level, Beth made it a creative adventure’. True. But if you want to join her on that journey, you’ll have to take your own pictures. As for Latin, like all good horticulturalists – who value precision – Chatto insisted on using the full, Latin botanical names for all the plants she wrote about. But she does seem less concerned about taste, at least not the kind that is an exercise in fitting a template – she says she groups plants in beds according to their shape and character, leaving their flower colour to an atypically jokey aside: ‘Colour schemes often seem to make themselves!’ That thrumming noise you can hear is Vita Sackville-West, creator of Sissinghurst and colour-scheme obsessive-in-chief, gyrating in her grave. When it comes to what the book has to teach, there’s still an abundance to enjoy. It begins with general but still useful advice about judging soil and climate. This quickly sidesteps into considerations about the challenges of Chatto’s own site – in 1958, an unpromising stretch of uncultivated sand, gravel, silty mud and bracken. Gardeners are nosy creatures, so this and all her other dips into the personal are gratifying. Then we get into moisture conservation (‘I really don’t hold with watering’), planting, fertilizing (‘we turn our [compost] heaps using the fork lift on the tractor’) and weed-control. Unlike many twenty-first-century gardeners, Chatto was perfectly sanguine about using violently chemical weedkillers, painting them on to the leaves of offending vegetation with a small brush – an image I rather like. Less appealing is her use of peat to help retain moisture. Public knowledge about the loss of peat bogs was still limited in the late 1970s, but you’d have hoped that, as the partner of a botanist, she’d have been more habitat-aware. After some design basics (‘hedges are a waste in the small dry garden’) we finally get to the really good stuff: plants, and how she uses them. This is where you see how creative Chatto was, and how influential. Don’t be surprised if, reading The Dry Garden now, you stumble across planting combinations that seem familiar. She describes filling the lowest layer of an oval island bed with dark green and cream crowns of Helleborus argutifolius, the fat, florid leaves of a purple bergenia, and spikes of the silver, grey and purple honesty Lunaria annua ‘Variegata’. I’d put good money on at least one of the show gardens at the next Chelsea Flower Show mixing the loose, self-seeding wildness of annuals like honesty with architectural foliage plants like hellebores or bergenias. Elsewhere, in the difficult, dry shade of the kind you get beneath a large deciduous tree, she suggests pairing the airy, elegant fern Dryopteris felix-mas with white foxgloves and groundcover ivy, interspersed with tufts of Bowles’ Golden Grass which, she says, look in spring like ‘patches of sunlight dropped through the leafless branches’. You can still see examples of this restrained, all-about-the-foliage style in the narrow, shady gardens of London townhouses. Those patches of dropping sunlight, though beautiful, are less typical. Don mentions that, on his first proper meeting with Chatto, she rather criticized his writing. That seems a case of the pot calling the Ming vase black. He is the most limpid of writers, probably better at communicating and evoking than he is at actual gardening. In a battle of horticulturalists, Chatto would be a world champion; but if the judges were scoring based on the poetry of her phrasing, she’d be out in round one. She’s still a pleasure to read, though, and not just because of the breadth of her knowledge. Chatto is one of those writers whose voice is so clear they could be standing next to you: slightly sharp, a tad bossy, never afraid to celebrate her successes, but equally unafraid of admitting mistakes. She’s no John Lewis-Stempel or Robert Macfarlane, either of whom can turn a bug on a leaf into a universe, but she still makes you see things, mostly by helping you understand them. This is her on Euphorbia characias subsp. wulfenii, a Chatto favourite:In February the flower spike proudly lifts its bent head and gradually opens its massed lime-yellow florets into a huge cylindrical dome . . . Although they will stand cold, they grow skinny if whirled around by tearing winds. The protection of other shrubs is enough to make them wax fat.Just try, next time you pass an E. characias, seeing its chubby, glaucous leaves without thinking of the phrase ‘wax fat’. The second half of the book initially looks as dry as a garden in August. It’s nothing more than an alphabetical list of plants, conversational in tone, but mostly concerned with the detail of where plants originated from, what they look like, and where you might grow them. For a gardener, though, this holds exactly the same pleasures as cooks get from recipes, or decorators from fabric samples: the chance to dream. The plants may not be illustrated, but Chatto’s words do a good enough job for the reader to indulge in some serious mind’s-eye gardening. Will the ‘great sheaves of shining evergreen leaves’ of Iris foetidissima var. citrina look good spearing through the ‘brassy yellow-edged’ lemon balm, Melissa officinalis ‘Aurea’? Dare you mix the floral, ‘butterfly charm’ of Cistus ‘Silver Pink’ with the ‘huge, waving, sea-blue and waxen’ foliage of Crambe maritima? Dare away. And while you do, look forward to a long, hot and very, very dry summer.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 65 © Isabel Lloyd 2020

About the contributor

Isabel Lloyd is co-author of Gardening for the Zombie Apocalypse: How to Grow Your Own Food When Civilization Collapses (or Even If It Doesn’t), published last year. She lives in London and Sussex and manages to kill plants in both places.