It arrived, as the inscription tells me, two months after my third birthday, a Christmas present from my mother’s brother, Uncle Basil. A large hardback book – to a 3-year-old very large, its fourteen inches height by almost ten width enough to give it immediate status: a book to wield as well as to read. The striking cover, in slightly acidic lemon yellow, had the single word Cocolo in brown, in a bold freehand. Below this was a small outline sketch of a donkey, a rather pot-bellied one with ears protruding from a wide-brimmed straw hat.

The first page is largely taken up by a picture of dolphins and large fish astern of a steamer making off. A cloud of smoke billowing from its funnel repeats the book’s title, along with the author’s name, given simply as ‘Bettina’. Behind the fish, in the middle of a calm blue sea, lies Ravaya-Reena, a miniature sandy island whose sole inhabitants turn out to be a fisherman, Babbo, his wife Mamma, their son Lucio, and Cocolo the donkey.

A closer view of the island shows a simple white house, with a washing-line and a few vines alongside, a small stand of pine trees, and a well at which Cocolo works, turning an overhead wheel to draw water. ‘Sometimes he stopped to think. Then Lucio called out to him: “Go on Cocolo! Turn round Cocolo!” And Cocolo turned round and round and round.’ This particular sentence is inseparable now from the memory of my mother’s voice, her delight evident as she read it aloud: an appreciation, perhaps, of the rhythm in the writing.

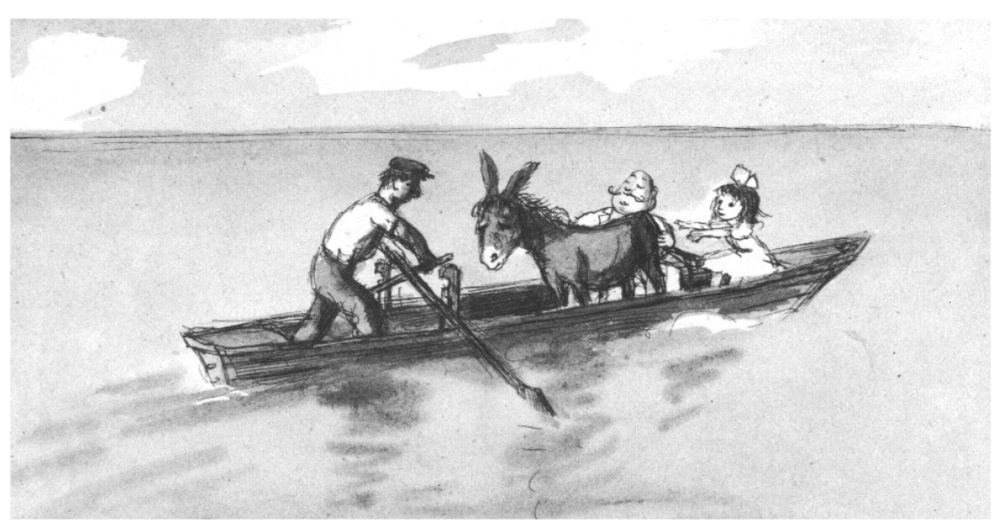

The narrative is triggered by an unintended visit to the island by one Mr Fatimus Greedy and his daughter Fussy. They live on the mainland in Port-Town, the white buildings of which are just visible from the island, across the strait. A trip in a smart motor-boat, with a picnic tea, goes horribly wrong when Mr Greedy carelessly shifts his bulk, causing the boat to capsize. Nightfall finds him floating off Ravaya-Reena, with Fussy si

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inIt arrived, as the inscription tells me, two months after my third birthday, a Christmas present from my mother’s brother, Uncle Basil. A large hardback book – to a 3-year-old very large, its fourteen inches height by almost ten width enough to give it immediate status: a book to wield as well as to read. The striking cover, in slightly acidic lemon yellow, had the single word Cocolo in brown, in a bold freehand. Below this was a small outline sketch of a donkey, a rather pot-bellied one with ears protruding from a wide-brimmed straw hat.

The first page is largely taken up by a picture of dolphins and large fish astern of a steamer making off. A cloud of smoke billowing from its funnel repeats the book’s title, along with the author’s name, given simply as ‘Bettina’. Behind the fish, in the middle of a calm blue sea, lies Ravaya-Reena, a miniature sandy island whose sole inhabitants turn out to be a fisherman, Babbo, his wife Mamma, their son Lucio, and Cocolo the donkey. A closer view of the island shows a simple white house, with a washing-line and a few vines alongside, a small stand of pine trees, and a well at which Cocolo works, turning an overhead wheel to draw water. ‘Sometimes he stopped to think. Then Lucio called out to him: “Go on Cocolo! Turn round Cocolo!” And Cocolo turned round and round and round.’ This particular sentence is inseparable now from the memory of my mother’s voice, her delight evident as she read it aloud: an appreciation, perhaps, of the rhythm in the writing. The narrative is triggered by an unintended visit to the island by one Mr Fatimus Greedy and his daughter Fussy. They live on the mainland in Port-Town, the white buildings of which are just visible from the island, across the strait. A trip in a smart motor-boat, with a picnic tea, goes horribly wrong when Mr Greedy carelessly shifts his bulk, causing the boat to capsize. Nightfall finds him floating off Ravaya-Reena, with Fussy sitting on his tummy, clinging to his tie and weeping. Babbo rescues them. The next morning, ‘when Fussy saw Cocolo in the sunshine, she loved him so much that she said she would not leave Ravaya-Reena unless he came with her’. Seduced by the prospect of enough money to buy new nets, Babbo reluctantly agrees to sell Cocolo. In his new home Cocolo becomes as spoilt as Fussy herself – until one day, riding him, Fussy loses her temper and kicks him hard. Offended and homesick, Cocolo tries to find his way home, but instead falls into the hands of Professor Fame, owner of a piano on wheels who busks in order to finance his love of wine. Stricken with remorse, Fussy falls ill. Then by chance Lucio, bringing fish caught with the new strong nets to sell in Port-Town, spots Cocolo and takes him back to the palatial Greedy residence. Fussy is restored and ‘as it was a lovely day they all decided to go to Ravaya-Reena in a brand new motor boat’. There Cocolo turns the wheel of the well again, Professor Fame buys Aiuta the mule, who had replaced Cocolo on the island, and there is much merrymaking. The final picture shows the townies heading back, after dark. By the pine trees, under a sky peppered with stars, Lucio and Cocolo ‘stood watching the boat until they could hear and see it no longer’. This operatic plot summary cannot do justice to the book. Like a good poem, it creates and then fulfils the terms of its own world with complete conviction. At first sight the illustrations are dominant – a series of fifteen double spreads: eight of them black-and-white lithographs, seven in subtle watercolours, all but one of the latter a single picture taking up both left- and right-hand pages. The text, which runs beneath the pictures, is rarely more than two or three lines long, and in only two instances in excess of five. The richness of the illustrations and the economy of the words chime wonderfully – as good and artless a match as the words and pictures in, say, Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are. And the names of the characters are not only apt and amusing, but a concise way of indicating character – Mr Fatimus Greedy (who appears in Bettina’s first children’s book, Poo-Tsee, the Water Tortoise, published in 1941), Professor Fame, or the ‘three most famous doctors of Port-Town’ who tend the ailing Fussy, Dr Barbalunga, Dr Baffineri and Dr Doloroso. As at least some of these names suggest, the world Cocolo evokes is the hot south, the Mediterranean at its most alluring, with more than a hint of Italy in the appearance of the Greedy palazzo, the streets of Port-Town and the road with sentinel cypresses that winds along by the sea. As for the island, it is Arcadia writ small, a simple enclave from which both a child and an adult reader might conjure an Edenic idyll. There are some books, particularly those we acquire early, keep and return to, that can be layered revelations. Renewing our familiarity with them, we are aware that we highlight different things at different times, and sense that this is not only a matter of the partial nature of recall, but also of our own changing knowledge and experience. So it was that when my father, a rare visitor, presented my 8-year-old self with one of his oil paintings, a view from the mainland of the island of Korcula, I recognized it easily as an amalgam of scenes from Cocolo – the hemmed-in streets clearly derived from Port-Town, the sense of a small island was obviously an allusion to Ravaya-Reena, and the vibrant aquamarine of the sea beneath a clarified sky must be part of the same ocean washing the shores of both. A few years later, when I went to a sailing school at Salcombe, I was allowed to row round the harbour at night in a snub-nosed tender; and at once identified the wonderful star-riddled sky with the final picture in Bettina’s book. Later still, other affinities accrued. I learned that Bettina was the writing name of Bettina Ehrlich (née Bauer), born in Vienna in 1903 – Vienna, capital of the country where my mother had once studied the piano, and for which she retained a lasting affection. In 1930 Bettina married the sculptor Georg Ehrlich. They had to leave Germany in 1938, and came to London – four years after my father had done likewise. Among the friends the Ehrlichs made in England were Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears, whom my uncle also knew (he was a film-maker, and Britten wrote music for the well-known documentary Night Mail, which he co-directed). It seems a reasonable speculation that it might have been Britten or Pears who pointed my uncle towards the book, which was published in the same year that he gave it to me. My continuing admiration for Cocolo also owes something to the antidote it offers (as do other new and classic children’s books) to the increasing Disneyfication of so many stories and fairy tales: a process that in some instances has also brought dire substitutes for fine original illustrations. There is something deeply dispiriting about the homogeneity represented by these block-jawed heroes and standard-issue princes, hordes of them, all apparently under-employed. They emerge from forests or just come riding by, saddlebags stuffed with chaste sample kisses, their passports to happily ever after in some castle modelled on a Bavarian fantasy such as Neuschwanstein. And the princesses they woo, coy and blushing, embryo drum majorettes, seem all much the same as one another. Worse still, perfectly good tales are invaded by hordes of birds and small, lachrymose forest creatures all high on empathy, blinking witnesses to misfortune and eager to scamper ahead to the next episode of the plot or, worst of all, to break into protracted crooning. In the face of such saccharine uniformity, books that avoid it have added merit. In common with the best of children’s books, Cocolo can speak quite differently to children and adults, but tellingly to both. For the child, it has something of the ache of unmediated longing and the simple vision of paradise that the young can intuit, even if it becomes too quickly intertwined with a premonition of its unavailability. For the adult reader, it can speak of homesickness and exile, aspects that are heightened in the context of the Ehrlichs’ flight to England. Now, as if it were a slow-release infusion, the story of Cocolo has assumed the nature of a full and virtuous circle. Two years ago I opened those lemon yellow covers once again, for the benefit of our 3-year-old twins, Rose and Grace, and was able to observe with delight how the magic goes on.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 22 © Lawrence Sail 2009

About the contributor

Lawrence Sail’s most recent collection of poems, Eye-Baby, was published by Bloodaxe Books in 2006.