I call them ‘also published by’ lists. Everyone who collects secondhand books knows them; hopeful publishers used to put them at the end of a volume. There you can find the memoirs of long-forgotten statesmen and long-gone generals, books on matters once thought topical (Is the Kaiser Insane?), collections, inevitably, of essays by E. V. Lucas and, of course, novels.

Very few of the names mean anything nowadays. Edgar Wallace is still remembered, a few people still read W. W. Jacobs, but most are forgotten. How many have even heard of Harold Bindloss, Justus M. Forman or Sir Gilbert Parker? A feature of the time which you won’t find now is the married couple who collaborated in writing. Agnes and Egerton Castle, Alice and Claude Askew, C. N. and A. M. Williamson are quite forgotten; driftwood, as the more portentous of them might have written, on the banks of Time’s river.

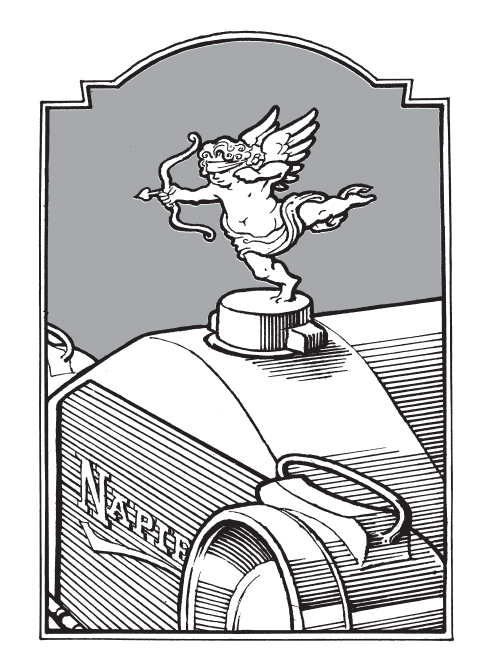

The Williamsons were perhaps the most intriguing pair, for they had an interesting speciality: the romantic motor touring story. They were writing in the early years of the twentieth century, when the car, still a novelty, had become reliable enough to be a sort of magic carpet to those who had the money. A writer who knew a little about cars and who could plan both a route and a romance had the key to a new kind of novel. Between them the Williamsons had all the skills that were needed.

Alice Muriel Livingston was born in Poughkeepsie in New York State in 1869 and showed early promise as a popular writer – she sold her first story at the age of 15. She came to England and in 1893 met Charles Norris Williamson who was editor of the Northcliffe magazine Black and White. She started by selling him a story. Two years later they were married and living in a ‘queer old Surrey farm-house’.

When they met, Williamson was 34. He was the son of an Exeter clergyman and after studying engineering at London University he went into journalism, specializing in t

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inI call them ‘also published by’ lists. Everyone who collects secondhand books knows them; hopeful publishers used to put them at the end of a volume. There you can find the memoirs of long-forgotten statesmen and long-gone generals, books on matters once thought topical (Is the Kaiser Insane?), collections, inevitably, of essays by E. V. Lucas and, of course, novels.

Very few of the names mean anything nowadays. Edgar Wallace is still remembered, a few people still read W. W. Jacobs, but most are forgotten. How many have even heard of Harold Bindloss, Justus M. Forman or Sir Gilbert Parker? A feature of the time which you won’t find now is the married couple who collaborated in writing. Agnes and Egerton Castle, Alice and Claude Askew, C. N. and A. M. Williamson are quite forgotten; driftwood, as the more portentous of them might have written, on the banks of Time’s river. The Williamsons were perhaps the most intriguing pair, for they had an interesting speciality: the romantic motor touring story. They were writing in the early years of the twentieth century, when the car, still a novelty, had become reliable enough to be a sort of magic carpet to those who had the money. A writer who knew a little about cars and who could plan both a route and a romance had the key to a new kind of novel. Between them the Williamsons had all the skills that were needed. Alice Muriel Livingston was born in Poughkeepsie in New York State in 1869 and showed early promise as a popular writer – she sold her first story at the age of 15. She came to England and in 1893 met Charles Norris Williamson who was editor of the Northcliffe magazine Black and White. She started by selling him a story. Two years later they were married and living in a ‘queer old Surrey farm-house’. When they met, Williamson was 34. He was the son of an Exeter clergyman and after studying engineering at London University he went into journalism, specializing in travel and, later, motoring. His wife once said, ‘Charlie Williamson could do anything in the world except write stories.’ A reading of even one of his novels will show that she was not far wrong. She, on the other hand, was a fountain of stories. As she also said, ‘I can’t do anything else.’ The technique with which they were so successful began with a series of articles on motor touring in France which Charles wrote for a newspaper that went out of business before publishing (or, presumably, paying) him. Using these as a framework Alice constructed a romantic story. The Lightning Conductor was published in 1903. The Lightning Conductor is in epistolary form – Alice was fond of this – and describes the adventures of a wealthy American girl, Molly Randolph, who buys a car from a casual acquaintance and decides to take it touring in France. We are not told the make of the car but, as one might expect, neither the car nor its former owner is reliable. Molly finds herself and her aunt stranded when it breaks down and the chauffeur (also supplied by the acquaintance) absconds with the money he has been given to buy a spare part. Fortunately for Molly, she is rescued by the owner of another, much superior, car, a Napier. By means too complicated to describe, the Napier’s owner, the Honourable John Winston, who is of course heir to a viscountcy, persuades her that he is a chauffeur named Brown. His employer, he tells her, wishes to drive himself, which leaves Brown temporarily unemployed. Molly is delighted to accept him as her chauffeur. Brown repairs and then drives her car while his own chauffeur follows secretly in the Napier, cleaning and servicing both at night. This business having become perhaps a little wearisome as a plot device, Alice solves her problem by setting fire to Molly’s bad bargain and having her characters go on in the Napier. (Winston’s chauffeur travels by train.) The Williamsons now give us a sweetened guidebook. We get not only descriptions of castles and places of interest, but even of the best point from which to view them. Of Blois they write, ‘The château does not show its best face to the riverside, being hemmed in by other buildings, so I drove past our hotel and on to the pretty green place where the great many-windowed château springs aloft from its huge foundation.’ We may hear Charles here; Alice provides the romantic story and the (sometimes rather gushing) descriptions of the countryside through which her travellers pass. The Lightning Conductor became a bestseller. Inspired by this they developed the technique of enjoying a motoring holiday, taking notes and producing a novel based on their experiences. Each novel had a guidebook content which introduced its readers to a different region. The Princess Passes was about walking in the Alps with a little motoring thrown in; Set in Silver was about touring in England. In The Heather Moon, as the name suggests, Alice set her story in a tour of Scotland. The Botor Chaperone, to make a change, was about a motor-boat cruise on the Dutch waterways. Italy, Spain, the Balkans all provided backgrounds for the Williamsons’ work. All their touring books had a mix of information which told their readers what to see – even, as in a visit to Haworth in Set in Silver, what to feel – in the places they might visit. To the modern palate Alice may seem a little too sweet, a little over given to fairyland, but her stories obviously delighted her readers. It seems likely that when they were researching a novel Charles planned the route and drove the car while Alice wove the story. How they must have enjoyed it! One of the Williamson characters was always an American, or at least of American descent, and this added to their appeal in the United States, where they sold well. Increasing success on both sides of the Atlantic made it possible for them to buy a house on the Riviera, where they lived an idyllic life. It would be interesting to know how much effect their work actually had on tourism. How many of their readers were inspired to follow the routes described in their books? How many, after all, could afford to? There is no doubt, however, that they had a public and their success in cheap editions shows that many people who could never hope to enjoy their exotic holidays still enjoyed their books. Social class is never far from their work. Alice loved disguise and mistaken identity, and the aristocrat disguised as servant occurs in several of their novels. In The Lightning Conductor, Molly several times remarks that it is a pity that ‘Brown’ is not a gentleman. That he clearly is one does not seem as obvious to her as to the reader, who, after all, has been let into the secret. When his true identity is revealed she takes a little time to become reconciled to the situation, but all ends happily, as we knew it would. The Williamsons show an interesting political sympathy in a sequel, The Lightning Conductor Discovers America. This novel of 1916 is another of their motor touring books, but it is set entirely in America, wartime Europe then being an unsuitable location for frivolous motoring. It is also, incidentally, an example of the danger of overloading a novel with factual content. Alice Muriel allows her interest in the history and sights of the eastern states to get in the way of the narrative. Not many, even in 1916, would have been much thrilled by a description of Washington Irving’s cottage, after all. One tends to skip quite large chunks of it. What makes it intriguing, however, is the sympathetic attitude shown to socialism – surely unusual in the context of early twentieth-century America. The story is told by Molly and Winston, who we first met in The Lightning Conductor. There is the usual false identity – the genuine heir to a fortune is present incognito. He has not revealed himself because he thought another character would make better use of the money, but he discovers that the man whom he allowed to inherit has abandoned his socialist beliefs, which were, of course, false from the beginning. Having made this discovery, the true heir reveals himself. He is not only a genuine heir, but also a genuine socialist (‘I was always a socialist at heart’). One might hesitate to describe the Williamsons’ politics as anything further left than pale pink, but who can doubt where their sympathies lie? Charles died in 1920, at the age of 61. Alice was devastated. She wrote more novels and some film scripts, but the days of romantic travel and happy collaboration were over. In 1933 she was found dead, having taken an overdose of sleeping pills. Nobody would suggest that the Williamsons were great contributors to the canon of English literature. Their books are undoubtedly trivial, but most of them remain readable a century after they were written – something which you couldn’t say of many a more respectable writer. None of them is in print now, of course, but it’s worth picking one up if you see it in a second-hand bookshop. You never know, you might enjoy it.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 21 © Brian Wood 2009

About the contributor

Brian Wood was born in Birmingham and lives, happily married, in rural Shropshire, where he is addicted to books and archery. He was a teacher for 30 years, until he achieved early retirement. Some of his pupils still speak to him.