When I worked on a national newspaper, an old, battered copy of The Times Atlas of the World stood propped against the Comment desk. The red cloth binding had come off and the signatures had fallen apart, like breakaway provinces seceding from a crumbling empire. As various benighted places – Darfur, Basra, Helmand – were thrust into the headlines, our reporters and subs would make off with the relevant pages. This battered relic featured countries that no longer existed: Czechoslovakia, the German Democratic Republic, Yugoslavia and, sprawling across a third of the planet, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

How quickly the world changes, while the atlases on our shelves remain frozen in the geopolitics of the moment at which they were printed. I have at home my mother’s old copy of Goodall and Darby’s University Atlas, published by George Philip in 1948; it is in fact a reprint of a pre-war edition, and across the Baltic republics, in red capitals, the legend incorporated in russia aug 1940 has been overprinted, while a dashed red line divides East Prussia into zones of Russian and Polish occupation as of 1945.

The Russian zone is now the Kaliningrad oblast, one of Europe’s strangest anomalies: an isolated pocket of Russian territory the size of Northern Ireland. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, it has been separated from the rest of the Russian Federation by Poland and Lithuania. Stranded amid the grim Soviet architecture of its eponymous capital are a few scant remains of the ancient Prussian city of Königsberg. When I was there a couple of years ago, a Russian, whose grandparents had migrated there from Sverdlovsk, told me: ‘History for us began in 1946. We didn’t know any of the old names.’ Marion Dönhoff, a Prussian countess who escaped the advance of the Red Army on horseback, called one of her volumes of memoirs Namen die keiner mehr nennt (‘Names no one speaks any more’), la

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inWhen I worked on a national newspaper, an old, battered copy of The Times Atlas of the World stood propped against the Comment desk. The red cloth binding had come off and the signatures had fallen apart, like breakaway provinces seceding from a crumbling empire. As various benighted places – Darfur, Basra, Helmand – were thrust into the headlines, our reporters and subs would make off with the relevant pages. This battered relic featured countries that no longer existed: Czechoslovakia, the German Democratic Republic, Yugoslavia and, sprawling across a third of the planet, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

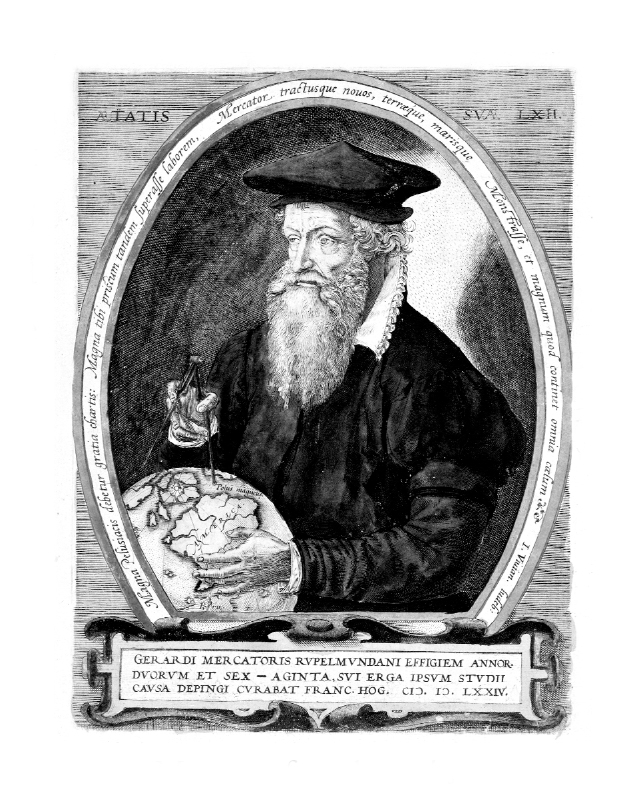

How quickly the world changes, while the atlases on our shelves remain frozen in the geopolitics of the moment at which they were printed. I have at home my mother’s old copy of Goodall and Darby’s University Atlas, published by George Philip in 1948; it is in fact a reprint of a pre-war edition, and across the Baltic republics, in red capitals, the legend incorporated in russia aug 1940 has been overprinted, while a dashed red line divides East Prussia into zones of Russian and Polish occupation as of 1945. The Russian zone is now the Kaliningrad oblast, one of Europe’s strangest anomalies: an isolated pocket of Russian territory the size of Northern Ireland. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, it has been separated from the rest of the Russian Federation by Poland and Lithuania. Stranded amid the grim Soviet architecture of its eponymous capital are a few scant remains of the ancient Prussian city of Königsberg. When I was there a couple of years ago, a Russian, whose grandparents had migrated there from Sverdlovsk, told me: ‘History for us began in 1946. We didn’t know any of the old names.’ Marion Dönhoff, a Prussian countess who escaped the advance of the Red Army on horseback, called one of her volumes of memoirs Namen die keiner mehr nennt (‘Names no one speaks any more’), lamenting the loss of old place names such as Eydtkuhnen, Palmnicken and Trakehnen – strange, lyrical and archaic, more Baltic than German. (These towns and villages are now Chernyshevskoye, Yantarny and Yasnaya Polyana respectively.) A still older volume, an 1869 edition of Philip’s Family Atlas which I found, on the brink of disintegration, in my local south London Oxfam shop and repaired myself, testifies to an earlier and now almost inconceivable political geography: a Turkey in Europe encompassing Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, Bosnia and much of Greece; an Austrian Empire stretching from Prague to Venice and from Lemberg (now Lviv in Ukraine) to Dubrovnik; and pre-unification Germany’s patchwork quilt of statelets – Anhalt, Brunswick, Hessen-Darmstadt, Sachsen-Coburg, Sachsen-Weimar, Waldeck. Above them looms the mighty Prussia which, just two years after the map was printed, would swallow them all. Atlases have been a familiar fixture in schools, offices, universities and homes for longer than any of us can remember, but it is worth bearing in mind that ‘the atlas’ came into being at a specific time and in a specific place. In the course of writing a series of illustrated histories of cartography, I have examined the rich collection of historic atlases in the Royal Geographical Society in London. Inhaling the dust rising from the stiff, creaking pages of these massive leather-bound folios, I was able to trace the birth and evolution of the form. The progenitor of them all is the Geographia of Claudius Ptolemy, a Greek geographer and astronomer working in Alexandria around ad 140. If his survey of the world as known to the ancients contained maps, they did not survive the long process of transcription and translation from Greek into Arabic and then, in the later Middle Ages, from Arabic into Latin. It did, however, contain tables of co-ordinates that allowed Renaissance cartographers to reconstruct his map of the world and the 28 regional maps, from Britain to Sri Lanka, that followed it. The copy in the RGS library was printed by Johannes Reger in Ulm, in 1486, its embossed leather covers fastened by metal clasps. Within, the luminous hand-colouring on its woodcut maps is as fresh as the day it was applied. Inside the front board, a bookplate reads: ‘William Morris, Kelmscott House’. The development of printing greatly facilitated the production and distribution of maps, and the process was accelerated in the mid-sixteenth century as woodcuts were superseded by copperplate engraving, which allowed greater accuracy and longer print runs. An enterprising Venetian publisher, Antonio Lafreri, began to bind maps by a variety of cartographers into folio volumes to the order of his customers; collectors call them IATO, ‘Italian, Assembled to Order’, atlases. The first atlas in the modern sense of a book of maps conceived and executed as a unity, however, was the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum published by Abraham Ortelius in Antwerp in 1570, which featured an engraving of Atlas, the Titan punished for his rebellion against the Olympians by being condemned to support the weight of the world on his shoulders. (A decade earlier, however, in 1559, William Cunningham’s The Cosmographical Glasse had depicted Ptolemy as Atlas, supporting an armillary sphere representing not just the Earth but the entire cosmos.) The word ‘atlas’ itself was first applied to a collection of maps by Ortelius’s friend Gerard Mercator, who in 1569 had devised the cylindrical projection that bears his name and became the definitive way of looking at the world for the next 400 years. He published the first four volumes of his atlas between 1585 and 1589, with a fifth being published by his son Rumold in 1595. For more than a century, the Low Countries would be at the forefront of European map-making, as a close-knit network of family businesses in Antwerp and Amsterdam produced a succession of ever-more detailed and elaborate maps, framed with ornate Baroque strapwork and embellished with ships, sea monsters and allegorical figures. In 1606 Jodocus Hondius bought Mercator’s plates and reissued his atlas, adding new maps. After Hondius’s death, they were sold to the globeand instrument-maker Willem Jansz Blaeu. His son Joan, official cartographer of the Dutch East India Company, continued the business, eventually publishing the family’s most celebrated work, the magnificent Atlas Maior, in 1665. This golden age of Dutch cartography only came to an end in 1672, when a fire at the Blaeu warehouse destroyed many of the plates. Why the Netherlands? One reason was that it lay on another of Europe’s geopolitical front lines, racked by a prolonged and bitter war between the newly independent, and Protestant, United Provinces in the north and Catholic Spain, which still controlled what is now Belgium. Hondius’s world map Typus Totius Orbis Terrarum, printed in Amsterdam around 1598, makes explicit reference to the conflict, depicting a Christian knight representing the French King Henri IV, an ally of the Dutch, fighting the figures of Vanity, Sin, Carnality, the Devil and Death, symbolizing the forces of Catholicism. While cartographers living in the crucible of Europe’s religious conflict endured hardship and oppression they were also able to maintain contacts on both sides of the politico-religious divide and so could draw on the discoveries of the seafarers of Spain, the Dutch East India Company and England, where religious exiles including Hondius and his brother-in-law Pieter van den Keere sought asylum and met Frobisher, Hakluyt and Norden. Religious wars notwithstanding, the Dutch succeeded in building a mercantile empire that ranged from New Amsterdam (New York) to South Africa and the far-flung islands of Indonesia, from where Abel Tasman charted the shores of Australia and New Zealand. The Low Countries became a cradle of art and science, infused with the humanist ideals of the Renaissance and supported by a flourishing merchant class who could afford to buy atlases and huge wall maps to display both their wealth and their global connections. Cartography was central to the culture: Ortelius was a friend of Pieter Brueghel the Elder, Vermeer’s painting The Geographer depicts a globe by Hondius and a sea chart by Willem Blaeu, while the marble floor of the Citizens’ Hall of the Koninklijk Paleis in Amsterdam is inlaid with maps of the eastern and western hemispheres. Several years ago, I visited the Plantin-Moretus Museum in Antwerp, where many of these great atlases were printed. It was a winter Sunday, and the city lay under snow. Built around an arcaded courtyard, the fine Baroque house was the home and place of business of the great Renaissance printer Christophe Plantin. His son-in-law Jan Moretus inherited it, and the family firm continued until the nineteenth century when it was finally overtaken by new technology, and the building was donated intact to the state as a museum. Thus, this powerhouse of the north European Renaissance has been preserved exactly as it was. On the ground floor stand the two oldest surviving printing presses in the world, complete sets of dies and matrices and, in the cabinets that line the walls, trays of movable type, some still in its original paper wrapping. Plantin mostly bought fonts from the great typographers of his day such as Garamond, but there is a type foundry here too, and a proof corrector’s room, with the desk directly under the window. The library contains not only books printed by Plantin, but also those of his competitors, and some incunabula. A large collection of atlases includes Ortelius’s Theatrum, the printing of which Plantin took over in 1579. Upstairs in the reception rooms hang 18 portraits commissioned by Balthasar Moretus from Rubens, including a posthumous likeness of Ortelius. As motes dance in the beams of sunlight falling through the leaded, mullioned windows, you feel as if you have indeed stepped into a Vermeer. Not all the great atlases of the period originated in the Low Countries, however. One of the glories of the RGS collection is a set of Braun and Hogenberg’s Civitates Orbis Terrarum. As the title suggests, the book, published in Cologne in six volumes between 1572 and 1617, was intended as a companion to Ortelius’s Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, focusing on cities rather than countries. All the great cities of Renaissance Europe and beyond are shown in plan, as panoramas or, most spectacularly, in 45-degree bird’s-eye views that are all the more astonishing because, two centuries before the Montgolfier brothers, such aerial perspectives could only be imagined. Georg Braun, a canon of Cologne Cathedral, compiled the text while Frans Hogenberg assembled the copperplate engravings, many of them based on drawings made on the spot by the artist Joris Hoefnagel. Here is London, ‘metropolis of the most fertile kingdom of England’, with Old St Paul’s and, on the south bank of the Thames, the bear- and bull-baiting rings; here is Constantinople, surrounded by shipping in the Golden Horn, the ruins of the Roman hippodrome still visible near Haghia Sophia and the Topkapi Palace; here are Mantua and Marseille, Cairo and Cuzco; and here is Florence, with Brunelleschi’s dome, looking much as it does today from the window of a plane coming in to land at the airport. These atlases enjoyed enormous success all across Europe. ‘Methinks it would well please any man’, wrote Robert Burton in The Anatomy of Melancholy, ‘to look upon a Geographical Map, to behold, as it were, all the remote Provinces, Towns, Cities of the World, and never to go forth of the limits of his study, to measure by the scale and compass their extent, distance, examine their site . . . What greater pleasure can there now be than to view those elaborate Maps of Ortelius, Mercator, Hondius &c, to peruse those books of cities, put out by Braunus and Hogenbergius?’ Few modern atlases aspire to the pictorial richness of Braun and Hogenberg, but as you peruse their comparatively sober maps, bear in mind the multiple layers of information – topographic, hydrographic, trigonometric, environmental, cultural and political – superimposed within these sophisticated artefacts. Drawing on millennia of knowledge, from ancient Babylonian astronomers to satellite positioning, they chart our growing understanding of the world we inhabit, and our impact upon it. All human life is here.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 37 © C. J. Schüler, 2013

About the contributor

C. J. Schüler’s Mapping the World was published in 2010 and his Mapping the City in 2012.