Alan Coren was on fire. Or, at least, smoking. He was also ablaze with enthusiasm. In due course, the cigarette was extinguished. The enthusiasm was not.

It was 2004 and he had come to see the archives of Punch, which the British Library had just acquired. Coren had worked on the magazine since the early 1960s and been its editor between 1978 and 1987. After he left, it went into a terminal decline, ceasing publication in April 1992. The title was eventually purchased by Mohamed Al Fayed and relaunched in 1996 but finally sank in 2002.

Not, however, without trace. Apart from the magazines themselves, a monumental run stretching over a century and a half, all sorts of flotsam and jetsam were left floating above the wreck. Over its lifetime Punch had accumulated a huge array of physical artefacts. These too had come to the Library, and a colleague and I now had the pleasure of reacquainting him with them. We began on the Library’s terrace, where the statue of Mr Punch, based on a drawing by Sir Bernard Partridge, had been re-erected. This had once graced the façade of the magazine’s Bouverie Street building, its prominent stomach leading this to be known as the Paunch Office. Alan Coren was entranced. ‘What bliss. The first sight of Britain foreigners will have on arriving at St Pancras is Punch’s arse!’

And so into the stacks. Amidst the array of portraits of former editors beginning with Mark Lemon – Punch, it was joked, was nothing without Lemon – and plaster busts of distinguished Punch figures such as Thackeray and Tom Taylor, not to mention various Punch costumes and Sir John Tenniel’s pipe bowl, he was particularly pleased to find an oil of a benign Mr Punch by Leonard Raven Hill, who drew for Punch between 1910 and 1940. The artist had given it to one of the proprietors but it had gone adrift. Coren, who was fiercely protective of the magazine and its history, had discovered it at a Ch

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inAlan Coren was on fire. Or, at least, smoking. He was also ablaze with enthusiasm. In due course, the cigarette was extinguished. The enthusiasm was not.

It was 2004 and he had come to see the archives of Punch, which the British Library had just acquired. Coren had worked on the magazine since the early 1960s and been its editor between 1978 and 1987. After he left, it went into a terminal decline, ceasing publication in April 1992. The title was eventually purchased by Mohamed Al Fayed and relaunched in 1996 but finally sank in 2002.

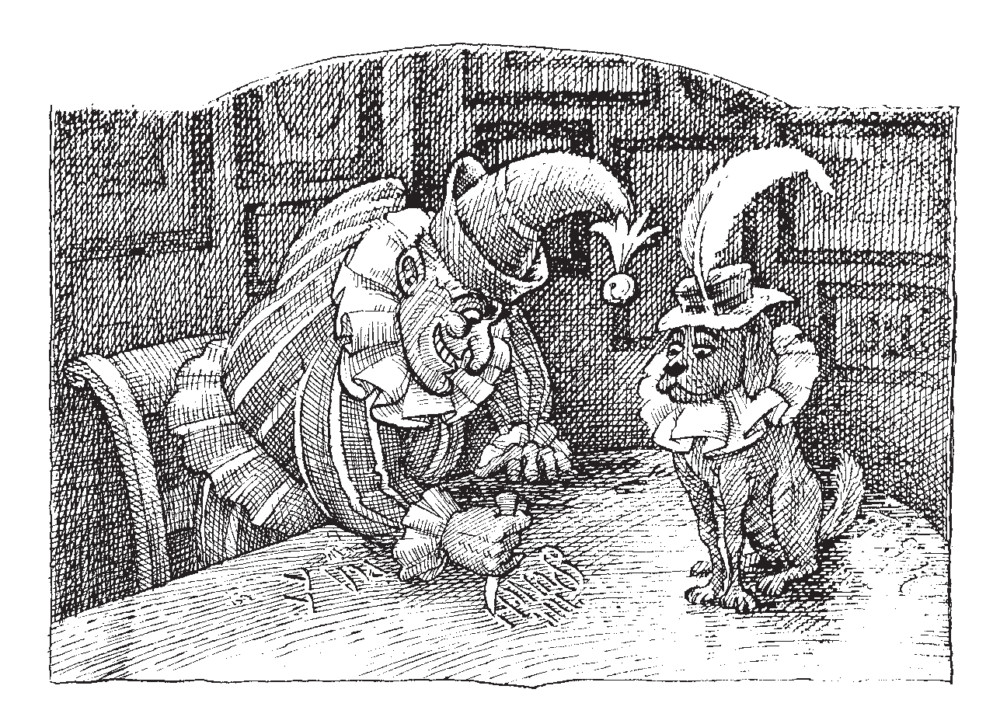

Not, however, without trace. Apart from the magazines themselves, a monumental run stretching over a century and a half, all sorts of flotsam and jetsam were left floating above the wreck. Over its lifetime Punch had accumulated a huge array of physical artefacts. These too had come to the Library, and a colleague and I now had the pleasure of reacquainting him with them. We began on the Library’s terrace, where the statue of Mr Punch, based on a drawing by Sir Bernard Partridge, had been re-erected. This had once graced the façade of the magazine’s Bouverie Street building, its prominent stomach leading this to be known as the Paunch Office. Alan Coren was entranced. ‘What bliss. The first sight of Britain foreigners will have on arriving at St Pancras is Punch’s arse!’ And so into the stacks. Amidst the array of portraits of former editors beginning with Mark Lemon – Punch, it was joked, was nothing without Lemon – and plaster busts of distinguished Punch figures such as Thackeray and Tom Taylor, not to mention various Punch costumes and Sir John Tenniel’s pipe bowl, he was particularly pleased to find an oil of a benign Mr Punch by Leonard Raven Hill, who drew for Punch between 1910 and 1940. The artist had given it to one of the proprietors but it had gone adrift. Coren, who was fiercely protective of the magazine and its history, had discovered it at a Chelsea art dealer’s in 1986 and bought it back. From a more recent period there were also a large number of photographs of Punch events and staff outings of which, since Punch’s proprietors had been solicitous of the well-being of their staff, there had been many. Given that Coren was famous for his muted enthusiasm for things Germanic, I could not resist asking him why amongst these there was a photograph of him sporting Tyrolean dress, the full fig of lederhosen and tufted Trachten hat, outside Buckingham Palace of all places. It turned out to be for a 1977 Punch article, under the byline ‘Man of a Thousand Trousers’, on British reactions to foreigners. ‘We all dressed up in silly costumes and sallied out. No one paid us a blind bit of notice.’ The biggest artefact by far, in fact one of the biggest in the whole Library, was the Punch table. From its very beginnings in 1841, the production of the magazine had been a convivial affair, much of itseditorial work conducted in taverns. Not long after Punch had been purchased by Bradbury and Evans in 1842 they installed a dining table in its offices. Thackeray, who was one of the contributors, called this ‘The Mahogany Tree’, but in fact it was only made of deal. This was just as well for pretty soon the diners began carving their initials around its rim. Over the lifetime of the magazine, the table had acquired ninety or so sets of initials. Probably the earliest were those of John Leech, whose subversive offerings in Punch of cartoons for paintings for the new Palace of Westminster gave the word its modern meaning of a humorous drawing. He had not only carved his initials and the date, 1854, but added his artist’s mark, a leech inside a bottle. This offering was appropriate as the main thing to be decided at dinners round the table was the subject of that week’s chief cartoon, ‘The Big Cut’. However, the most elegant initials have to be those of Thackeray. Coren explained that the proprietors sat at one end of the table and the editor at the other. He had carved his own initials twice, first when he had been invited to join the table, and then when he had become editor. I was able to point out that not only did the Library have the table itself but also the mallet and chisel with which in latter days the initials were carved. The dinners had once been monumental, if only for the amount of food and champagne consumed. Henry Silver, an early staff member whose 1860s diary of them is in the collection, lists mock turtle, red mullet, turbot, saddle of mutton and boiled fowl, kidneys and ptarmigan on one occasion and whitebait, pickled salmon, sole, chicken, cold lamb and London pudding on another. They eventually grew more sedate. In 1925 they became lunches and after William Davis, Coren’s predecessor, took the helm in 1969 he banished editorial discussions from the board. They were now purely social occasions, an opportunity for the staff to meet politicians, journalists and celebrities. There had always been guests at the table. They had included Charles Dickens, Sir Joseph Paxton – it was Punch, after all, which had christened his most famous building the Crystal Palace – and Sir John Millais. When in 1907 Mark Twain dined, he was invited to carve his initials but declined, saying that two of Thackeray’s initials could stand for him. Nevertheless, six ‘strangers’ did add their initials. One was James Thurber; the other five were royal. In its early days, Punch had been markedly radical. By 1866, however, Tom Taylor, a Punch stalwart and future editor, though chiefly remembered today as the author of Our American Cousin, the play Abraham Lincoln was watching when he was assassinated, was dining with the Prince of Wales at the Garrick Club. And then Punch writers and cartoonists began to be knighted. So it was that the table now bears the initials of both the Duke of Edinburgh, whom Coren once described as ‘barking royal’, and the present Prince of Wales. There were, on the other hand, less august guests. One of these was the magician Uri Geller, noted for his supposed telekinetic powers. The Punch archive contains a fork which he bent. ‘It wasn’t only a fork,’ Coren said. ‘He also did for a ladle. And one of my colleagues rang me up afterwards to say that he couldn’t get into his house. His keys had bent in his pocket.’ What to look at next? I doubted whether Alan Coren would be particularly interested in his own files of business correspondence, even the letter signed ‘Nero Canal’ and purporting to come from the office cleaners. What distinguished the archive, however, as it had Punch itself, were the cartoons. There were over 1,700 autographed drawings of them. This is, of course, only a minute selection of those which had been published over the years. Most had been discarded, for it took almost a century for the value of the original artwork to be recognized. When it was, many were sold or simply given away. What, I asked, had been Coren’s favourite cartoon? ‘Easy. The man at the Titanic offices leading a polar bear with the caption “Yes, but is there any news of the iceberg?”’ It was a 1968 offering by Bill Tidy, sadly not in the collection. Tidy felt an affinity with the sea, which Coren was to make much use of. He even procured him a berth on a British nuclear submarine. It promptly broke down and had to be towed back to Gibraltar. The irony was, though no one connected with the magazine realized it at the time, that the vessel which was truly doomed was the one they were on. Punch was destined to be the Titanic of humorous magazines, the biggest and, in its day, the best. And, like the Titanic . . .Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 48 © C. J. Wright 2015

About the contributor

C. J. Wright was Keeper of Manuscripts at the British Library until his retirement in 2005.