On a motorbike ride across southern Italy in the Sixties, I stopped at an outdoor café in a hilltop village somewhere in the middle of Basilicata. A group of men and boys gathered a few yards away and, with that unnerving look of blank curiosity and suppressed hostility which you sometimes encounter in peasant areas, watched in silence while I drank my coffee. My discomfort ended only when they turned to inspect the much more interesting English motorcycle, a big old 350cc BSA. One of the boys mumbled a comment, and the ice was broken.

Late last summer I found myself once more crossing the region, in the reverse direction this time, driving with my wife in a hired car.

The grape-harvest had begun when we set off in an end-of-summer cloudburst from the vineyards of Puglia behind Taranto. We called first at Castellaneta, clinging perilously to the lip of its ravine, climbed a smooth yellow-paved street past the birthplace of the film idol Rudolph Valentino and reached the cathedral on the very edge of the chasm. It was closed, of course, for restauro.

Matera greeted us with a graveyard of scarecrows set on a rocky promontory. Dressed in gaudy rags with punctured footballs for heads, the figures were hung on rough wooden crucifixes round the still smoking embers of a fire. We visited the grimly magnificent troglodyte city in the canyon below the modern town. Here 20,000 people and their animals once lived in malarial destitution. A foetid smell came from abandoned cave dwellings; the well-made rock houses seemed deserted also, but for the mournful sound of a saxophone from an upper room which echoed round the canyon.

Eight miles out of Matera we passed a sign marked ‘Grassano’. A bell rang in my head. Wasn’t this the place described by Carlo Levi in Christ Stopped at Eboli, his famous account of Italian peasant lif

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inOn a motorbike ride across southern Italy in the Sixties, I stopped at an outdoor café in a hilltop village somewhere in the middle of Basilicata. A group of men and boys gathered a few yards away and, with that unnerving look of blank curiosity and suppressed hostility which you sometimes encounter in peasant areas, watched in silence while I drank my coffee. My discomfort ended only when they turned to inspect the much more interesting English motorcycle, a big old 350cc BSA. One of the boys mumbled a comment, and the ice was broken.

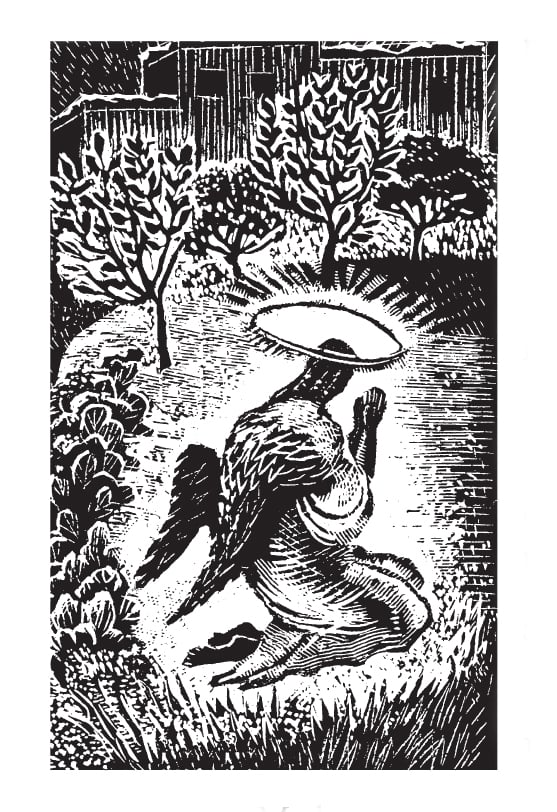

Late last summer I found myself once more crossing the region, in the reverse direction this time, driving with my wife in a hired car. The grape-harvest had begun when we set off in an end-of-summer cloudburst from the vineyards of Puglia behind Taranto. We called first at Castellaneta, clinging perilously to the lip of its ravine, climbed a smooth yellow-paved street past the birthplace of the film idol Rudolph Valentino and reached the cathedral on the very edge of the chasm. It was closed, of course, for restauro. Matera greeted us with a graveyard of scarecrows set on a rocky promontory. Dressed in gaudy rags with punctured footballs for heads, the figures were hung on rough wooden crucifixes round the still smoking embers of a fire. We visited the grimly magnificent troglodyte city in the canyon below the modern town. Here 20,000 people and their animals once lived in malarial destitution. A foetid smell came from abandoned cave dwellings; the well-made rock houses seemed deserted also, but for the mournful sound of a saxophone from an upper room which echoed round the canyon. Eight miles out of Matera we passed a sign marked ‘Grassano’. A bell rang in my head. Wasn’t this the place described by Carlo Levi in Christ Stopped at Eboli, his famous account of Italian peasant life in the 1930s? We debated whether to turn off. But the rain was sheeting down and we drove on over the ridge to the Basento River and swung west towards Potenza. Then, like a rebuke, another sign appeared. This time we had to follow it. The road curled between high rocks, climbing back up to the ridge. And then the rain stopped, the sky cleared and, looking up, we saw Grassano as Levi described it: ‘A streak of white at the summit of a bare hill, a sort of miniature imaginary Jerusalem in the solitude of the desert’. After many wrong turnings and dead ends, we found the Corso Umberto, the main street that runs like a terraced promenade across the sloping face of the village. It was decked out with gantries for a festa. Of the sheep and goats that Levi described running up and down the alleys on either side of the Corso there was no sign; nor of the ‘half-naked, pale, puffy children chasing one another among the rubbish’. We asked a barman for directions to Prisco’s inn, where the political exile began his sentence, and were directed to a house along the street. The door was opened by an old lady who ushered us into a cool, dark, marble-floored sitting-room stuffed with objects, and asked us to wait while she summoned her son-in-law. This woman was the daughter of Vincenzo Prisco, owner of the former pensione. Did she remember Carlo Levi? ‘You understand I was a girl of only 10 at the time,’ she replied. ‘But yes, I remember him.’ The son-in-law took us next door and showed us the room in which Levi slept and which he sometimes shared with local travellers. A window gave out on to the Basento valley and the opposing slopes of the Accettura mountains. The room was clean and modern, its walls covered with old photographs and framed copies of the author’s paintings. There were books for sale and a DVD. Our guide was joined now by his teenage son, who was itching to work the computer for us. ‘We don’t get many visitors, unfortunately,’ said our guide. ‘Especially not from England.’ We asked about Aliano (‘Gagliano’ in the book), the even more remote village 20 miles to the south to which Levi was consigned after six weeks at Grassano. ‘I am from Aliano myself,’ said the curator. ‘I could send you to people there. But why don’t you stay with us tonight? I can find you lodgings, and we could meet for supper and talk about the past.’ He treated us like visitors from another world. Levi himself said of his arrival on 3 August 1935, ‘I felt as if I had fallen from the sky, like a stone into a pond.’ This was another Italy. The 32-year-old intellectual from Turin, born into a prosperous borghese family, an anti-fascist polemicist and successful painter who had exhibited in Paris and London and at the Venice Biennale, landed like a missionary in darkest Africa. The peasants felt sorry for him, because he had become, like them, a victim of Fate and of the ever-oppressive state. After the initial shock, the greatest enemy was boredom. ‘In the monotony of the passing hours there was place for neither memory nor hope; the past and the future were two separate unrippled pools,’ he wrote. The peasants had a dialect word, crai, for their hopeless future, which they used in an ironic chant for the days of the week: ‘Crai, pescrai, pescrille, pescruflo, maruflo, marflone, maruflicchio.’ Poverty, illness and despair were the peasants’ lot. As for the local ‘gentry’, trapped by lack of talent or ambition they nurtured old rivalries and mutual hatreds. Their lack of charity, no less than the superstition of the peasants, was what made people say, ‘We’re not Christians here. Christ got no further than Eboli.’ Eboli, on the edge of the Campanian plain about 100 miles to the west, marked the end of civilization. The prisoner was saved by two things, his painterly powers of observation and his medical training. Levi’s artistic curiosity led him not only to study his new neighbours and put them on canvas, but also to record for us in language equally vivid the colours, shapes and emotions of the strange world in which they lived. He had trained as a doctor; but because he had never practised he felt unqualified to treat the peasants. They, however, would not be refused. They regarded him as a man of miracles far superior to their ignorant village physicians and witch-doctors. Like that other writer-doctor Chekhov, Levi enjoyed unique access to the villagers’ inner lives. It brought him comfort, too. One night, at the lonely farmhouse to which he had been summoned, he lay awake listening to the cries of a man who was dying of a ruptured appendix:Like any city boy, Levi was intrigued by rustic methods. He watched a peasant take the skin off a goat by applying his lips to a cut in its back leg and blowing it up like a balloon. He described how the red-headed pig doctor spayed the young sows: hauling the intestines out, whipping off the ovaries and throwing them to his dogs, stuffing back the guts and stitching up the belly – and all so deftly that the pig, though it screamed blue murder, ran off quite unharmed. Taking a nap one afternoon at the bottom of a newly dug grave, he met the ancient sexton, a man taunted by the village women for his lack of virility but feared for his power over wolves. In this world the devil would masquerade as a mad-eyed goat, and hidden treasure was guarded by red-hooded gnomes, the spirits of unbaptized children. A monstrous dog encountered on the track at moonlight swallowed twenty-four bullets from a Mauser automatic and exploded into thin air when the sign of the cross was made over it. Cures were effected by rhyming spells, amulets and old coins, toads’ bones and pictures of saints – magic no more harmful than the pills routinely handed out by the local doctors. Lost babies were retrieved, under the guidance of the Black Madonna of Viggiano, from the lairs of wolves; and angels stood guard every night outside the peasants’ cottages. Within days of his arrival at Aliano, Levi was warned against accepting any drink from a woman: she was certain to lace it with a love potion made of menstrual blood. Because men were in short supply (Aliano, with a population of 1,200, had no fewer than 2,000 men living in America), illegitimate babies were no disgrace. But it was taboo for a woman of any age to be alone with a man, because no human power could prevent them having sex. The strict code of peasant morality which city folk talked about was a myth:Death was in the house: I loved these peasants and I was sad and humiliated by my powerlessness against it. Why, then, at the same time, did a great feeling of peace pervade me? I felt detached from every earthly thing and place, lost in a no man’s land far from time and reality . . . An immense happiness, such as I had never known, swept over me . . .

All this made it difficult to find a housekeeper. The only suitable candidates were the ‘witches’. Carlo Levi acquired the well-named Giulia Venere, tall and shapely and of an archaic beauty but already, at 41, ‘wrinkled with age and yellowed with malaria’. The mistress of the former priest, she had endured seventeen pregnancies from fifteen men. Giulia was shocked that her boss did not want to make love to her. But superstitiously she refused to sit for her portrait until he slapped her and threatened to beat her, when – so he said – she submitted happily. What Levi learned among the peasants was how distant and irrelevant but oppressive was the state. And he came to see that his political friends in the north, even those who hated fascism, felt a subconscious veneration for the state, as if it were endowed with an ethical personality which ‘transcended both its citizens and their lives’. As for the much-discussed ‘problem of the Mezzogiorno’ – of southern Italy – the state could never solve it because it was itself the problem. Only a network of self-governing communities, in which the peasants had a direct interest, could relieve their poverty and indifference. Carlo Levi was released from exile in May 1936, after ten months of a three-year sentence, thanks to a general amnesty declared by Mussolini at the fall of Addis Ababa in Italy’s war against Abyssinia. The peasants begged him to stay, to marry Donna Concetta, the prettiest girl in Aliano, and become mayor. They threatened to puncture the tyres of the car that came to fetch him. ‘If you go, you’ll never come back,’ they said. ‘You’re a real Christian, a real human being.’ After taking refuge in France, Levi returned to Italy in 1942 to help the partisans, and wrote his famous book in Florence the following year. He became a senator, wrote more books (hardly known outside Italy) and painted portraits of his famous contemporaries. But he did go back, on several occasions, especially to Grassano where he took photographs of the peasants for a huge panel painting called Lucania ’61. On his death in Rome in 1975, however, his remains were transported not to the village that made him welcome, but to Aliano. In 1978, his book was turned into a film by the director Francesco Rosi; it is faithful to the original, even if set largely in the ultra-gothic location of Craco, a neighbouring hill town. The book did more than begin a realist trend in Italian literature. It changed its author’s life. And it changed the perspective of all of us who read it: after such revelations none of us could ever again suppose that peasant life was some kind of idyll to be defended against the ravages of progress. Grassano has doubled in size now, and some of the old quarter has been rebuilt following an earthquake in 1980. Agriculture is subsidized by distant Brussels, but the landscape looks much the same. The goats and donkeys have gone, along with most of the wolves. The abandoned cave houses of Matera are being done up as summer houses for the borghesi. The ‘problem of the South’ has been solved, not by the transformation of the state that Levi prescribed, but by the disappearance of the peasants themselves. Here, as in the rest of southern Europe, lives were changed not by the arrival of Christianity but by a miracolo economico in which Christ appears to have played little part. The state survived, reformed and purged of ideology, perhaps, but hardly more responsive than before. We gazed from the window of Carlo Levi’s room and saw the storm clouds massing over the mountains. We thanked the curator of the Levi shrine, hastened back to our car and descended into the valley, skimming along the flooded highway towards a hotel we had booked above Potenza. We regretted having turned down the invitation to stay and celebrate, and we regret it still.Behind their veils, the women were like wild beasts. They thought of nothing but love-making . . . and they spoke of it with a licence and simplicity of language that were astonishing. When you went by them on the street their black eyes stared at you, with a slanting downward glance as if to measure your virility . . .

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 25 © Christian Tyler 2010

About the contributor

Christian Tyler long ago gave up motorbikes for writing, but still thinks they’re the best way to travel in strange places.