On one of my more recent trips to Ireland, I took a detour through County Waterford to visit Lismore Castle. Towering over the steep, wooded banks of the Blackwater, it was built nearly 900 years ago by an English prince, was once owned by Sir Walter Raleigh and has been the Irish seat of the Dukes of Devonshire since the eighteenth century. The castle is a fairytale sight but what caught my eye, given pride of place on one distinctly ancient and sturdy-looking wall, was a plaque. Said wall, it explained, replaced one that had collapsed ‘for no apparent reason’. No more, no less. I was, briefly, bemused; on reflection, quite the opposite. That precise phrase recurs, to pointed and poignant effect, in Troubles, J. G. Farrell’s sublime tragicomedy about the dying days of Ireland’s Protestant Ascendancy. As I sheltered from the rain, by now rather less soft than it’s fabled to be, in the lee of that notable wall, it struck me as the perfect summation of the entire Anglo-Irish predicament.

I was on a pilgrimage to Castletownshend, the West Cork crucible of a unique and celebrated writing partnership, appreciation of whose work is one of my infallible yardsticks of congeniality. When not quite into my teens, I noticed that my parents were unusually taken with a television series called The Irish RM, ‘based on stories by Anglo-Irish novelists Somerville and Ross’. Broadcast in the UK in the early 1980s, when the IRA was committing some of its worst atrocities on the mainland, it was an early and, perhaps, surprising success for the then new Channel 4. More beggar than chooser, I settled down to watch with them and was soon hooked on the galloping misadventures of Major Sinclair Yeates who, as the eponymous Resident Magistrate, arrives in turn-of-the-century western Ireland fresh from his regiment and appointed by the Lord Lieutenant to administer justice; or so he hopes.

No one ‘of Irish extraction’ is born free of

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inOn one of my more recent trips to Ireland, I took a detour through County Waterford to visit Lismore Castle. Towering over the steep, wooded banks of the Blackwater, it was built nearly 900 years ago by an English prince, was once owned by Sir Walter Raleigh and has been the Irish seat of the Dukes of Devonshire since the eighteenth century. The castle is a fairytale sight but what caught my eye, given pride of place on one distinctly ancient and sturdy-looking wall, was a plaque. Said wall, it explained, replaced one that had collapsed ‘for no apparent reason’. No more, no less. I was, briefly, bemused; on reflection, quite the opposite. That precise phrase recurs, to pointed and poignant effect, in Troubles, J. G. Farrell’s sublime tragicomedy about the dying days of Ireland’s Protestant Ascendancy. As I sheltered from the rain, by now rather less soft than it’s fabled to be, in the lee of that notable wall, it struck me as the perfect summation of the entire Anglo-Irish predicament.

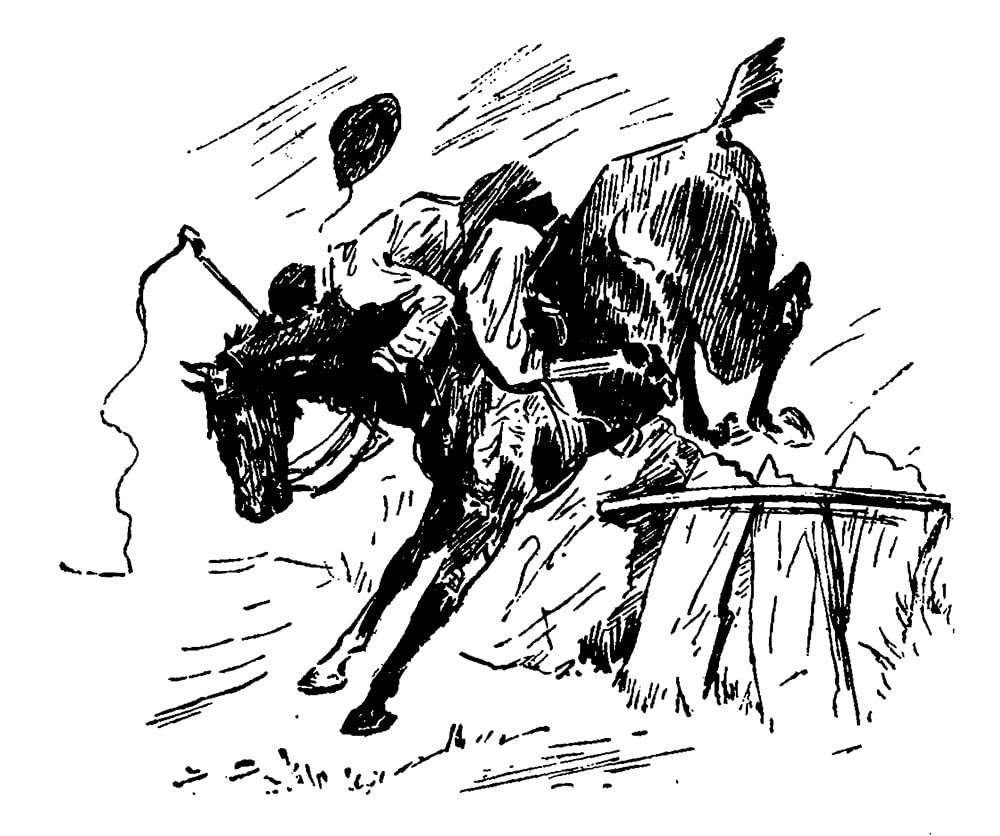

I was on a pilgrimage to Castletownshend, the West Cork crucible of a unique and celebrated writing partnership, appreciation of whose work is one of my infallible yardsticks of congeniality. When not quite into my teens, I noticed that my parents were unusually taken with a television series called The Irish RM, ‘based on stories by Anglo-Irish novelists Somerville and Ross’. Broadcast in the UK in the early 1980s, when the IRA was committing some of its worst atrocities on the mainland, it was an early and, perhaps, surprising success for the then new Channel 4. More beggar than chooser, I settled down to watch with them and was soon hooked on the galloping misadventures of Major Sinclair Yeates who, as the eponymous Resident Magistrate, arrives in turn-of-the-century western Ireland fresh from his regiment and appointed by the Lord Lieutenant to administer justice; or so he hopes. No one ‘of Irish extraction’ is born free of history but back then, in relative ignorance, I enjoyed the programmes as a simple period sitcom, squirming as Yeates (a perfectly cast Peter Bowles) was merrily disabused of the notion that his position commanded any respect from the horse-trading, hard-hunting and hard-drinking denizens of Skebawn (think Skibbereen) who are, it transpires, also hard-wired to outfox him at every turn. That said, I couldn’t fail to catch shades of my immediate family in this world of no tomorrows where the idiom rang familiar, and complex snobberies went hand-in-glove with that peculiarly Irish disdain for ‘mock swank’ or delusions of grandeur. It was, however, some years before I actually read any of the original Irish RM stories; when I did, so much suddenly made sense. Edith Somerville of Drishane House, Castletownshend, and her second cousin Violet Martin (always ‘Ross’, after her Galway home) were introduced in 1886 at Somerville’s large and convivial home, the hub of a seaside village crowded with extended family, all ferociously talented and pathologically busy. By the standards of the day, neither was in her first flush (‘we were, as we then thought, well stricken in years . . . not absolutely the earliest morning of life; say, about half-past ten o’clock, with breakfast (and all traces of bread and butter) cleared away’). From that moment, neither looked back. Somerville had been born in Corfu where her officer father was stationed but by the age of 27, when she met the woman who was to become her professional partner and soul-mate, this avowed spinster (‘I’d love to be an ould maid. A single life is airy.’) was not only an accomplished musician and horsewoman but also unusually well- travelled, a positive Home-ruler and determined – by necessity as much as conviction and having trained in London, Paris and Düsseldorf – to make her living as an artist (‘I will paint. I will also work.’). Ross, four years younger but already a published writer, arrived into this ‘clanging heronry’ from a far quieter nest of gentlefolk. Reduced to penury – and staunch Unionism – by unpaid rents, the Martins were one of the Tribes of Galway whose estates had once extended to over 200,000 acres. Both hailed from that elusive breed best understood in terms of its loyalty to the English crown but variously described as the Ascendancy, hyphenated-Irish or, with the contempt indulged in by those deeming themselves authentically Irish, West Britons. Survivors of successive English plantations dating back to Elizabeth I but in retreat since the 1800 Acts of Union and beleaguered by absenteeism, Catholic emancipation and land reform, they were the tenacious ‘horse Protestants’ of propaganda (who were, ironically, to furnish many of the prime movers of the emergent Free State). Knowing this centaur class from within, the pair soon set about immortalizing its fugitive charms. They began with a ‘Buddh’ dictionary (Buddhs being all descendants of their common great-grandfather, the ‘silver-tongued’ former Lord Chief Justice of Ireland, Charles Kendal Bushe). Vital for ‘situations in which the English language failed to provide sufficient intensity’, it gives a flavour of the cousins’ shared eye for pretension, ear for speech and incorrigible nose for absurdity:Minaundering pres. p. of verb used to describe the transparent devices of hussies (deriv. from the Fr. ‘minauder’ translated as ‘to mince, to simper, to smirk’). Medear n. Method of address – seldom implying affection. White-eye n. A significant and chilling glance calculated to awake the fatuous to a sense of their folly.It was a short step to their first novel (An Irish Cousin, 1889) but one hard fought. Penelope Fitzgerald, an ardent admirer, was indignant on their behalf that they were ‘treated as the joke of the family’ when, for their part, they consciously looked back to Maria Edgeworth for example, commending her ‘sincerity’ and sharing her ‘privilege’ of ‘living in Ireland, in the country, and among the people’ of whom they wrote. By the time Lady Gregory boasted of being ‘the first to write in . . . the English of Gaelic thinking people’, they were already busy ‘eavesdropping’: ‘Ireland has two languages: one of them is her own by birthright; the second of them is believed to be English, which is a fallacy; it is a fabric built by Irish architects with English bricks, quite unlike anything of English construction . . . expressing with every breath the mind of its makers.’ Pastiche was anathema (neither had much truck with the Celtic Revival and its efforts to mythologize a heroic past). What inspired them was their own, dwindling microcosm of ordered chaos. Seven novels later – including The Real Charlotte (1894), which V. S. Pritchett rated the best Irish novel of any period – Somerville and Ross embarked on a collection of short stories entitled Some Experiences of an Irish RM (1899) as a riposte to a London editor’s sneer about ‘an overdose of Ireland’. This was followed by two more collections, Further Experiences of an Irish RM (1908) and In Mr Knox’s Country (1915). Written in the middle of those fraught three decades between the loss of Charles Stewart Parnell – champion of Home Rule – and the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, the stories tackle the impasse between occupier and occupied in a spirit of irreverent fatality. Politics and religion flicker (officials from Dublin Castle and nationalist Catholic clerics both get short shrift) but the tales derive their finest comedy from class conflict as much as racial difference, blithely comparing a terminal situation to ‘a gigantic picnic in a foreign land’. In each, the animating crisis is always in prospect but its form and degree are anyone’s guess. Narrated by the hapless Major Yeates – like Bertie Wooster, a Magdalen man – there’s never a dull moment nor the slightest hope that he’ll prevail over the self-serving machinations of his landlord and fellow member of the bench, Flurry Knox (‘a stableboy among gentlemen and a gentleman among stableboys’); Flurry’s redoubtable grandmother, old Mrs Knox (‘a rag-bag held together by diamond brooches’); his housekeeper Mrs Cadogan (‘a name made locally possible by being pronounced Caydogawn’ and borrowed, tongue firmly in cheek, from the reigning Viceroy); or Flurry’s mendacious groom Slipper. Even Yeates’s game and sprightly wife, Philippa, is reduced to stitches at her husband’s expense by all but the most dire and muddy predicament. Throughout, all parties are, by and large, gleefully complicit in the farce afoot, typically involving untimely exits and entrances, wayward animals and copious liquor. The prevailing shamelessness and unsentimental witness to the tooth and claw of country life – framed by exquisite descriptions of Ireland’s wild beauty and rendered in pitch-perfect vernacular – would be easy to confuse with condescension. Instead, calamity after calamity testifies to ‘the inveterate supremacy in Ireland of the Personal Element’ (a mantra to which, in the story ‘Poisson d’Avril’, Yeates nobly clings through mounting vicissitudes involving a dead salmon). No one should be surprised when Slipper the groom, ‘with the manner of the confederate who had waded shoulder to shoulder with me through gore’, tenders the following advice: ‘It’s hunting you should be, in place of sending poor divils to gaol.’ Forget Wilde’s quip about the unspeakable in pursuit of the inedible. You barely need to know a hoof from a halter to appreciate the genius with which this pioneering pair captured ‘the unsuspected intoxication of fox-hunting’. Until the fall which precipitated Ross’s premature death in 1915, both were addicted to the chase. It was perfect fodder for breakneck sagas such as ‘The Pug-Nosed Fox’ in which Yeates, installed as Deputy MFH in Flurry’s absence (‘Be fighting my grandmother for her subscription, and whatever you do, don’t give more than half a crown for a donkey. There’s no meat on them.’) finds himself separated from the field and not only supernumerary at a wedding feast, a feast just demolished by his pack, but even proposing the toast . . . As with Wodehouse, nominating a favourite is as impossible as analysing the stories’ magic but ‘Trinket’s Colt’ exemplifies what Somerville later defined as ‘the art of being jolly in creditable circumstances’. Hold hard as Flurry – bent on turning a profit on his grandmother’s prize foal – inveigles Yeates into a little light larceny, fortified by ‘sherry that . . . would burn the shell off an egg’. Culprit and stolen colt have just found themselves eyeball to eyeball in a furze-fringed, sandy grave when Mrs Knox heaves into view. To Somerville – who continued to write under their joint names until her death in 1949 – their collaboration was ‘like blue and yellow which together make green’. Ross dubbed it their ‘Irish eye’. Not for them the anxiety Elizabeth Bowen described feeling ‘English in Ireland, Irish in England’; but they would not have disputed her claim that in relation to Ireland ‘no fiction could improve upon or exaggerate reality’. The Irish RM stories can get lost in translation, mistaken for rather suspect caricature. That’s precisely the point. The joke falls on the impecunious Anglo-Irish as much as it appears, at first glance, to be at the expense of the ‘native’ Irish, its edge all the keener for the deep and never-to-be-admitted sympathy between them. Somehow, they make lasting sense of a vanished world and remind me, somehow, of that inscrutable plaque.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 71 © Caroline Jackson 2021

About the contributor

Caroline Jackson read English at Oxford but was brought up to believe the best English is spoken in Dublin. She now lives in Cambridge and spends her days looking west to where the grass is definitely greener.