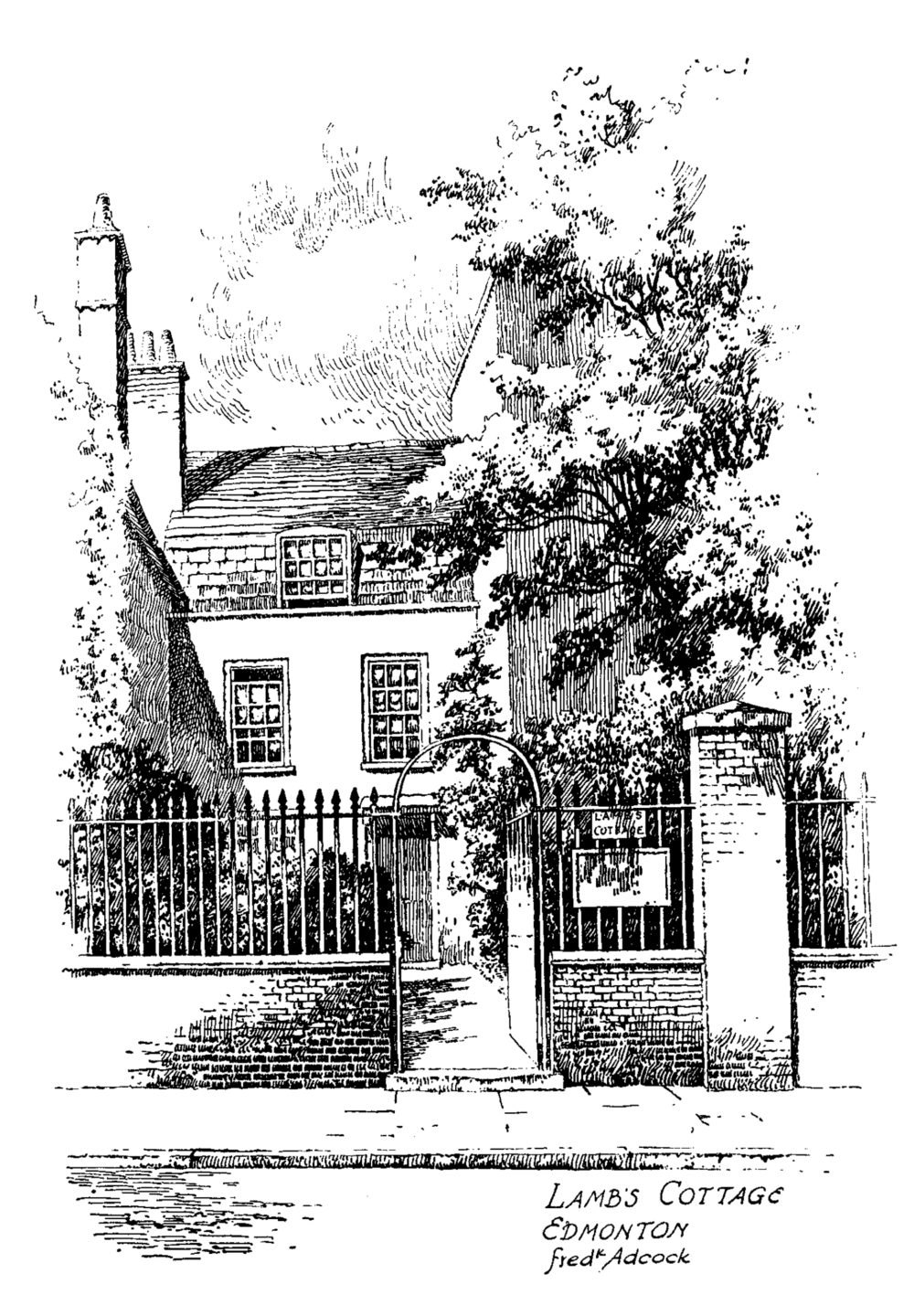

In the north London suburb of Edmonton where I grew up, virtually the only feature of note is Charles Lamb’s cottage in Church Street, which is marked with a blue plaque. The essayist lived there in the first half of the nineteenth century. Lamb was born in 1775 and in 1792 began thirty-three years of tedious work as a clerk at the East India Company counting-house. Over the length of his adult life he lived – on and off – with his sister Mary. Their story is told in Sarah Burton’s highly readable A Double Life: A Biography of Charles and Mary Lamb (2003).

The incident that was to define the lives of both siblings occurred in 1796. Mary had a congenital mental condition, and in a fit of madness stabbed her mother through the heart while the family was at dinner. She was committed to a madhouse but within two and a half years was freed from official constraint and put into the care of her brother Charles. Yet in most years thereafter she needed to spend further time in care. A friend reported chancing upon the pair in the street one day as Charles, carrying a straitjacket, escorted his sister to Hoxton asylum.

The wretchedness of such scenes was in marked contrast to Mary’s behaviour when in normal health. Their friend William Hazlitt wrote of ‘the sweetness of her disposition, the clearness of her understanding and the gentle wisdom of all her acts and words’, and he seemed to speak for all who knew her. Charles was devoted to his sister and she to him. Their mutual supportiveness, in life and in their literary work, is often compared to that of Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy.

When Mary was well, the Lambs were renowned for their hospitality and – in Charles’s case – a good deal of hard drinking. Friends included literary luminaries such as Coleridge, Wordsworth and Hazlitt, plus an unusually wide circle of eccentrics. Lamb wrote that he had never made any lasting friends ‘that had not some tincture of the absurd in

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inIn the north London suburb of Edmonton where I grew up, virtually the only feature of note is Charles Lamb’s cottage in Church Street, which is marked with a blue plaque. The essayist lived there in the first half of the nineteenth century. Lamb was born in 1775 and in 1792 began thirty-three years of tedious work as a clerk at the East India Company counting-house. Over the length of his adult life he lived – on and off – with his sister Mary. Their story is told in Sarah Burton’s highly readable A Double Life: A Biography of Charles and Mary Lamb (2003).

The incident that was to define the lives of both siblings occurred in 1796. Mary had a congenital mental condition, and in a fit of madness stabbed her mother through the heart while the family was at dinner. She was committed to a madhouse but within two and a half years was freed from official constraint and put into the care of her brother Charles. Yet in most years thereafter she needed to spend further time in care. A friend reported chancing upon the pair in the street one day as Charles, carrying a straitjacket, escorted his sister to Hoxton asylum. The wretchedness of such scenes was in marked contrast to Mary’s behaviour when in normal health. Their friend William Hazlitt wrote of ‘the sweetness of her disposition, the clearness of her understanding and the gentle wisdom of all her acts and words’, and he seemed to speak for all who knew her. Charles was devoted to his sister and she to him. Their mutual supportiveness, in life and in their literary work, is often compared to that of Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy. When Mary was well, the Lambs were renowned for their hospitality and – in Charles’s case – a good deal of hard drinking. Friends included literary luminaries such as Coleridge, Wordsworth and Hazlitt, plus an unusually wide circle of eccentrics. Lamb wrote that he had never made any lasting friends ‘that had not some tincture of the absurd in their characters’. His intimates ‘were in the world’s eye a ragged regiment. [I] found them floating on the surface of society.’ Against their extraordinary background it is surprising that the Lambs got any writing done at all. An early collaboration was their Tales from Shakespeare (1807), which summarized for children the plots of twenty plays and became the most successful thing either of them wrote – it is still in print today in more than a dozen editions. It was Mary who received the commission to write the Tales and did most of the work, though this has not always been made clear – witness the ascription of authorship on the title pages of modern editions, where Charles’s name is always placed before his sister’s, if indeed she gets mentioned at all. In fact the limpid clarity of the prose points to Mary, because her brother’s writing was characterized by (in his own words) ‘antique modes and phrases’. Charles was slow to find the literary voice that ultimately made him famous. He started by contributing jokey anecdotes to the Morning Post, then had poems included in a collection edited by Coleridge and wrote some unsuccessful plays and some well-received literary criticism. From the age of 35 he began writing essays, and ten years later was contributing regularly to the London Magazine, which led eventually to a separate publication, Essays of Elia (1823). The pseudonym was borrowed from a clerk at South Sea House where Lamb had once worked. Elia was an anagram for ‘a lie’, which suited Lamb’s custom of writing ironically under the guise of different voices, so that the reader never knew exactly who had done what. The medium was to bring Lamb a national reputation and to swell the always modest income that he and Mary survived on. It helped that this was the heyday of the essay form, with Lamb and Hazlitt its best-known practitioners. In writing this article I used an edition of Essays of Elia that I’d hung on to as a keepsake. It came from a series of several dozen classic books that had belonged to my mother, and formed the bedrock of her intensive reading when – as the custom went in those days – she was sent out to work at the age of 15. She bought the books on subscription from Odham’s Press during the 1920s and 1930s. They were identically bound in maroon with old-fashioned gold lettering on the spines. It is hard to sum up the flavour of Lamb’s essays. He had little interest in politics. The arts were well represented, with literature and the theatre prominent, but not music (‘Organically I am incapable of a tune’). The unpredictability of subject matter is suggested by three essays that appear side by side: ‘The Tombs in the Abbey’ is a diatribe against the practice of charging for entrance to Westminster Abbey; ‘Amicus redivivus’ describes how a short-sighted friend of the family had to be rescued from drowning when he accidentally walked into the river near Lamb’s house; and ‘Barbara S—’ records how a child actress, working thirty years before Lamb’s birth, was mistakenly paid double the going rate for a week’s work and agonized over whether to give the money back. Nor is the title of an essay a reliable guide to its content, since Lamb was famous for his digressions. So ‘The Old Margate Hoy’ dwells briefly on the delights of a seaside holiday but is mostly about a fellow-passenger met on a boat who was ‘the greatest liar I had met with then or since’; and ‘Old China’ has one page on Lamb’s liking for china jars and saucers and four charming pages on how buying things gave Mary and himself the most pleasure in the days when they were poor. Some essays manage to stay within the bounds of their nominal subject. ‘A Dissertation upon a Roast Pig’ floats the absurd conceit that roast pork was discovered when a Chinese family accidentally burnt down their flimsy cottage with a litter of newborn piglets inside. Raking through the remains, the father picked up an incinerated piglet and instinctively licked his fingers after burning them on the crackling. Thereafter neighbours noticed that every time the family’s sow farrowed, the rebuilt cottage would be in flames again. Perhaps the most affecting writing uses Lamb’s idiosyncratic humour to illuminate unchanging elements of everyday life. ‘Poor Relations’, for instance:Lamb’s writing commitments were discharged despite his years of unpalatable grind in the counting-house – six days a week, with a single week off in summer. When he was 50 his employers offered a pension, which allowed him a few years of freedom at the end of his life. This piece of luck provoked some sober reflections: ‘That is the only true Time that a man may call his own – that which he has all to himself; the rest, though in some sense he may be said to live it, is other people’s Time, not his.’ But still the humour bubbles up, albeit suffused with sadness:A poor relation is the most irrelevant thing in nature – a piece of impertinent correspondency – an odious approximation – a haunting conscience – a preposterous shadow, lengthening in the noon-tide of our prosperity . . . He is known by his knock . . . He entereth smiling and embarrassed . . . He casually looketh in about dinner time when the table is full. He offereth to go away, seeing you have company, but is induced to stay. He fill-eth a chair and your visitor’s two children are accommodated at a side-table . . . He declareth against fish, the turbot being small, yet suffereth himself to be importuned into a slice, against his first resolution . . .

The elegant Slightly Foxed mug, much mourned (because no longer available), carried a second-hand quote from Lamb taken from the very first issue of Slightly Foxed: ‘Charles Lamb once told Coleridge he was especially fond of books containing traces of buttered muffins.’ Today Lamb is less quoted than he might have been, due in part to the complexity of his style. Still, the work contains many interesting sentiments expressed in original ways, like the eight examples below, only one of which is among the thirty-nine Lamb-isms in the current Oxford Dictionary of Quotations:I am no longer clerk to the Firm of, etc. I am Retired Leisure. I am to be met with in trim gardens. I am already come to be known by my vacant face and careless gesture, perambulating at no fixed pace, nor with any settled purpose. I walk about; not to and from.

Just before Christmas 1834 Lamb fell over in Edmonton High Street. He grazed his forehead, contracted a fatal skin infection and died within the week. His sister Mary survived him by thirteen troubled years. Their joint grave is in the grounds of All Saints Church, Edmonton. Lamb’s cottage – Edmonton’s celebrated tourist spot – cannot have been a cheerful home for his last two years because it was actually a small, privately run madhouse where Mary was committed and where Charles went to be with her. When you peer through the front gate today the place has a rather sombre look. I doubt whether today’s batch of Edmonton schoolteachers urge their pupils – as mine did – to visit the cottage; and I very much doubt whether those pupils read Essays of Elia, because they are fast becoming a footnote in English literary history. Yet when reading about the Lambs I imagine the riotous evenings they presided over among their wide circle of friends and regret that Lamb did not have his own Boswell; and I still relish the quirky, uneven, funny, perceptive and inimitable style of a pre-eminent English essayist.(On the convalescent) How sickness enlarges the dimensions of a man’s self to himself! He is his own exclusive subject.

(On the borrower) He cometh to you with a smile and troubleth you with no receipt.

(On reading) When I am not walking, I am reading. I cannot sit and think. Books think for me.

(On newspapers) Newspapers always excite curiosity. No one ever lays one down without a feeling of disappointment.

(On poverty) There is some merit in putting a handsome face upon indigent circumstances.

(On distant correspondents) It is not easy work to set about a correspondence at our distance. The weary work of waters between us oppresses the imagination.

(On drinking) The drinking man is never less himself than during his sober intervals.

(On drinking) To mortgage miserable morrows for nights of madness . . . are the wages of buffoonery and death.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 64 © David Spiller 2019

About the contributor

David Spiller lived in Edmonton for the first twenty-three years of his life and was indoctrinated into the Lambs by his primary school teacher, Marjorie Morse.