I think we can all agree on the restorative qualities of a country walk. Certainly, since I moved to Sussex, I have come to value walking as much more than a basic mode of transport, surrounded as I am by the tranquillity of fields, footpaths and woods. I only wish I could convince my daughter of the splendours on our doorstep.

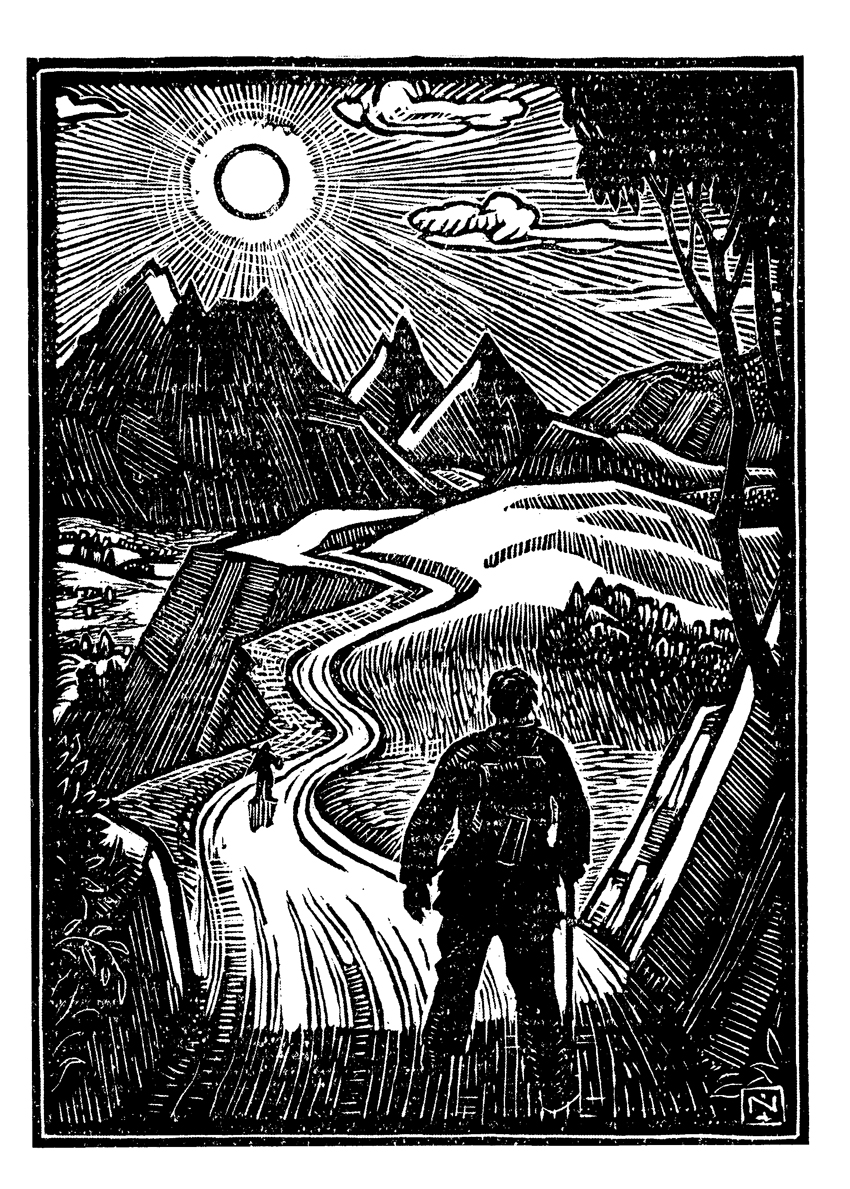

In my search for something to inspire my beloved refusenik I landed upon a little book by Stephen Graham called The Gentle Art of Tramping (1926), which has recently been reprinted in a handsome little hardback edition by Bloomsbury. My eyes have been opened to a far more profound approach to perambulation than I ever expected. Tramping, in this case, is approximately a cross between rambling and hiking, more serious than the one and less intense than the other, with an emphasis on living off the land, sleeping outdoors and ignoring wristwatches.

It is written by a real master of the art. Stephen Graham (1884–1975) was an adventurer and journalist best known for his accounts of his treks on foot in Russia. Books such as A Vagabond in the Caucasus and With the Russian Pilgrims to Jerusalem told not only of his huge feats of pedestrianism but also his enduring sympathy for working people. When he enlisted in the Scots Guards during the Great War, he eschewed a commission in order to enter the ranks as a private. He wrote movingly of the life of the recruit in A Private in the Guards, a critique of the army’s method of building a soldier by breaking the man. In The Gentle Art of Tramping he transfers his vagrant skills and subversive instincts to a more intimate British setting because, as he very wisely says, ‘There are thrills unspeakable in Rutland, more perhaps than on the road

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inI think we can all agree on the restorative qualities of a country walk. Certainly, since I moved to Sussex, I have come to value walking as much more than a basic mode of transport, surrounded as I am by the tranquillity of fields, footpaths and woods. I only wish I could convince my daughter of the splendours on our doorstep.

In my search for something to inspire my beloved refusenik I landed upon a little book by Stephen Graham called The Gentle Art of Tramping (1926), which has recently been reprinted in a handsome little hardback edition by Bloomsbury. My eyes have been opened to a far more profound approach to perambulation than I ever expected. Tramping, in this case, is approximately a cross between rambling and hiking, more serious than the one and less intense than the other, with an emphasis on living off the land, sleeping outdoors and ignoring wristwatches. It is written by a real master of the art. Stephen Graham (1884–1975) was an adventurer and journalist best known for his accounts of his treks on foot in Russia. Books such as A Vagabond in the Caucasus and With the Russian Pilgrims to Jerusalem told not only of his huge feats of pedestrianism but also his enduring sympathy for working people. When he enlisted in the Scots Guards during the Great War, he eschewed a commission in order to enter the ranks as a private. He wrote movingly of the life of the recruit in A Private in the Guards, a critique of the army’s method of building a soldier by breaking the man. In The Gentle Art of Tramping he transfers his vagrant skills and subversive instincts to a more intimate British setting because, as he very wisely says, ‘There are thrills unspeakable in Rutland, more perhaps than on the road to Khiva. Quality makes good tramping, not quantity.’He walked for the sun and the wind, for the joy and pride of his prowess in walking, and to get from one place to the other. Therefore his writing . . . is just English open country.You could say the same of Graham, whose aim in this book is to encourage the urban dweller to reconnect with the country and so with themselves. It is an aim that is, as he acknowledges, at odds with the general flow of modern life:

You will discern that going tramping is at first an act of rebellion; only afterwards do you get free from rebelliousness as Nature sweetens your mind. Town makes men contentious; the country smooths out their souls.As someone who commutes most days from country to town and back again, I can only concur, and apologize for my occasional contentiousness.

You are going to be very ill-mannered and stray on to other people’s property. Granted that fundamental impertinence you must be as nice as possible about it; graciously lift your hat to the proprietor when you see him.

I listen with pained reluctance to those who claim to have walked forty or fifty miles a day. But it is a pleasure to meet the man who has learned the art of going slowly, the man who disdained not to linger in the happy morning hours, to watch, to exist. Life is like a road; you hurry, and the end of it is grave.In a funny way, he wants readers to regain their sense of themselves and their country by forgetting all those characteristics that we are told make us British in the first place. It is such an attractive proposition precisely because it is so contrary to our conditioning and so lyrically expressed. Graham is well aware that the escape to the country is for almost all of his readers temporary, restricted to weekends and holidays. He is realistic enough to acknowledge that people can’t live their whole lives in his parallel world. The economics of modern life, alas, just don’t allow it. Rather, he sees it as a way to preserve sanity and perspective, and as a great social leveller: ‘It is no small part of the gentle art of tramping to accept the simple and humble role and not to crave respect, honour, obeisance.’ A staunch democrat, he would no doubt point out that, once you have paid for your coffee pot, sturdy boots and pocket edition of Horace, tramping is, unlike most mod- ern therapies, open to all and absolutely free.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 69 © Chris Saunders 2021

About the contributor

Chris Saunders is the managing director of Henry Sotheran Ltd, Britain’s oldest antiquarian bookseller. He is also a writer on bookish matters and runs the literary blog Speaks Volumes. He shares his house in East Sussex with his wife, daughter and hundreds of books, some of which he’s read.