Every Thursday morning for twenty years and more, the Orkney writer George Mackay Brown cleared a breakfast-table space among the teacups and the marmalade and, sitting with his elbows among the crumbs, picked up a cheap biro and jotted down 400 words on a notepad. It was a letter to the local newspaper, The Orcadian, for publication the following Thursday, and as such was written to entertain an island community of fewer than 2,000 souls. Through the small window of the simple council house – just a few steps away – the sea glimmered and whispered.

The unpretentious and elemental setting for these scribblings, as he called them, was a felt feature in everything that Mackay Brown ever wrote. Poet, short-story writer, novelist, dramatist – it didn’t matter which magic hat he was wearing, the words that came out of it were worlds away from the computer screen and the desk. Word-processing was an occupation unknown to him – and also a paradox that made him shudder. You can process peas, he once said to me, but language deserves better, and a writer is not a robot. Mackay Brown was a craftsman and a bard and he would spin a web of words with exquisite delicacy, not as the spider and spin-doctor do, to entrap and deceive, but as the minstrel does, to enchant and beguile.

Letters to a rural rag, on the other hand – even as you say it, the word ‘ephemera’ comes to mind. Except that George Mackay Brown was incapable of writing a dull sentence, a fact that a small Edinburgh publisher recognized and celebrated by making three selections of the best of these weekly letters and awarding them the permanence of book covers. Thus Letters from Hamnavoe (1971-5), Under Brinkie’s Brae (1976-9) and Rockpools and Daffodils (1979-91) span two decades of letters from one of the greatest wordsmiths of the last century and easily, in my view, Scotland’s finest writer of that time.

They are not, of course, letters, except in the sense that they are from a man of the same: they are rather essays, miniature meditations – prose-poems, some of them – on an unpredictable variety of topics: illness and ale, the elemen

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inEvery Thursday morning for twenty years and more, the Orkney writer George Mackay Brown cleared a breakfast-table space among the teacups and the marmalade and, sitting with his elbows among the crumbs, picked up a cheap biro and jotted down 400 words on a notepad. It was a letter to the local newspaper, The Orcadian, for publication the following Thursday, and as such was written to entertain an island community of fewer than 2,000 souls. Through the small window of the simple council house – just a few steps away – the sea glimmered and whispered.

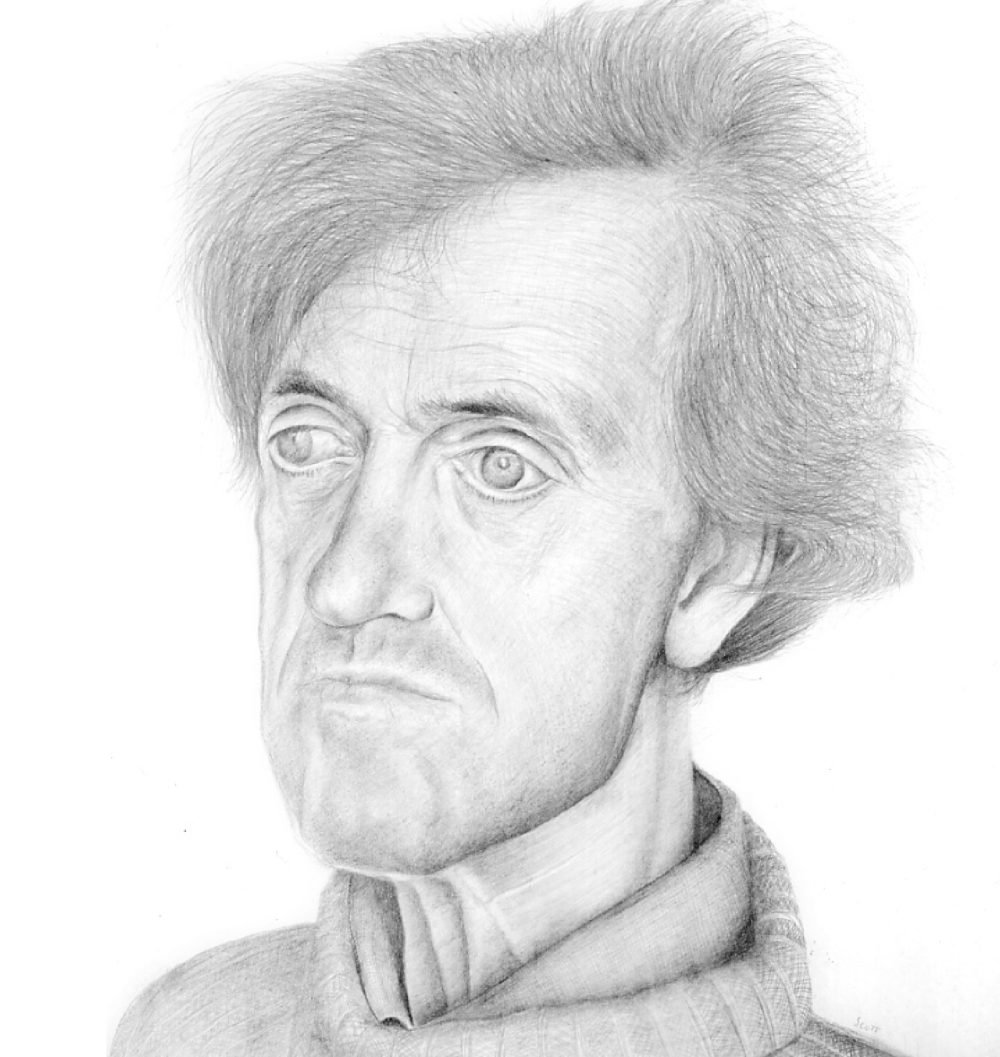

The unpretentious and elemental setting for these scribblings, as he called them, was a felt feature in everything that Mackay Brown ever wrote. Poet, short-story writer, novelist, dramatist – it didn’t matter which magic hat he was wearing, the words that came out of it were worlds away from the computer screen and the desk. Word-processing was an occupation unknown to him – and also a paradox that made him shudder. You can process peas, he once said to me, but language deserves better, and a writer is not a robot. Mackay Brown was a craftsman and a bard and he would spin a web of words with exquisite delicacy, not as the spider and spin-doctor do, to entrap and deceive, but as the minstrel does, to enchant and beguile. Letters to a rural rag, on the other hand – even as you say it, the word ‘ephemera’ comes to mind. Except that George Mackay Brown was incapable of writing a dull sentence, a fact that a small Edinburgh publisher recognized and celebrated by making three selections of the best of these weekly letters and awarding them the permanence of book covers. Thus Letters from Hamnavoe (1971-5), Under Brinkie’s Brae (1976-9) and Rockpools and Daffodils (1979-91) span two decades of letters from one of the greatest wordsmiths of the last century and easily, in my view, Scotland’s finest writer of that time. They are not, of course, letters, except in the sense that they are from a man of the same: they are rather essays, miniature meditations – prose-poems, some of them – on an unpredictable variety of topics: illness and ale, the elements, the arts, Sean O’Casey, Solzhenitsyn, past and present, food, festivals and flavours of the week, biros and bluebottles and the voyage of St Brendan – and on it goes. The delight lies in the sheer spontaneity of the exercise; the not knowing what will come next. George Mackay Brown would have revelled in the Augustan age, exemplifying the original idea behind the word essay: an attempt – an effort to tackle anything from a headache to the Fall of Man, and conjure up a mix of entertainment and instruction to a charmed circle of readers. His literary roots also stretch back to the world of the Nordic skald and medieval makar: willing to perform to order, ready to concede that there is no such thing as an unpoetic subject. The result is that these disparate musings are yoked gently together by the sheer craftsmanship of the writer, over whose plainest pronouncements there is a wash of lyricism, insistent and muted as the sea. They are united too by their Orcadian themes, which turn out to be universal. Like Hardy or Faulkner or Burns, Mackay Brown illustrates the truth that you don’t achieve universality by tearing up your roots and stamping on your sources. Yeats realized this better than anybody when he said that everything that the great poets see has its relation to the local life and through that to the universal life. Nothing is an isolated artistic moment. And this universal unity is attainable only through what happens to be near you, your nation, your village, the cobwebs on your wall – the only things you know even a little about. These are the gloves with which you reach out and touch the universe. There is no better example of this in modern times than George Mackay Brown. There is one other unity in these letters that is infinitely refreshing. You won’t find much in them on the big issues of politics, the economy, education, agriculture, religion, wars and rumours of war, or the rise and fall of rotten regimes. Mackay Brown concentrates both on homelier matters and bigger forces: darkness and light, time and tide, soup and potatoes, and rain over Rackwick. Like Blake, offering you eternity in the palm of his hand, Brown’s vision encompasses the whole of Orkney’s history in one harmonious weave. Quickly you inhabit the Orkney psyche and the Circe of these islands begins to work the spell, threatening to turn you into one of the many stones that stand and stay. Read these letters and at once you will feel the pull of the place – and of its very own Prospero. Look for example at the description of the afternoon of the winter solstice at Maeshowe – one of the many Neolithic burial chambers that sprinkle the little green world of Orkney – in which he makes it into a monument to its own ancestors, turning the islands into the gentlest of graveyards, where Stone Age and computer age folk lie side by side, inhabiting the same earth. The Neolithic builders didn’t have computers but they knew nature better than we do, and in a treeless environment, where everything was made of stone (and still is), they laid stone upon stone with breath-taking precision. Maeshowe was so constructed that at sunset on the winter solstice the dying midwinter sun would send its last probe into the tomb, a final finger of light filtering up the long low tunnel to touch, fleetingly, the inner wall of the burial chamber, where the dead lay waiting for that magical moment: a seed of brightness at the time of the year’s deepest darkness, a symbol of spring to come, and a splash of resurrection. Time and again Mackay Brown returns to it, unable to resist the gravitational pull of a past that still informs the present:The winter sun hangs just over the ridge of the Coolags. Its setting will seal the shortest day of the year, the winter solstice. At this season the sun is a pale wick between two gulfs of darkness. Surely there could be no darker place in the bewintered world than the interior of Maeshowe. It holds, like a black honeycomb, the cells of the dead. Stoop through the long narrow corridor towards the chamber of darkness, winter, death. Now the hills of Hoy – strangely similar in shape to Maeshowe – are about to take the dying sun and huddle it away. The sun sends out a few last weak beams. One of the light rays is caught in this stone web of death. Through the long corridor it has found its way; it splashes the far wall of the chamber. (In five or six thousand years there has been, one assumes, a slight wobble in the earth’s axis; originally, on that first solstice, the last of the sun would have struck directly on the tomb where possibly the king-priest was lying with all his grave-goods around him.) The illumination lasts for a few minutes, then is quenched. It is a brief fleeting thing; yet it is a seal on the dying year, a pledge of renewal. The sun will not renege on its ancient treaty with men and the earth and all the creatures.Or look at the contribution for 2 June 1977, in which the author receives a parcel from a Norwegian friend, Liv Schei. The parcel contained a gramophone record called Veg Vet en Vind, a collection of the songs of Erik Bye, the Norwegian TV producer and songwriter, and Mackay Brown was drawn to the song entitled ‘Margareta’s Vise’. The Margareta of the song was the daughter of the thirteenth- century king of Scotland, Alexander III. She crossed the North Sea to marry Erik, the boy-king of Norway, though she herself was at the time a mature young woman. Mackay Brown delved into the historical documents called Diplomatarium Norvegicum and gasped when he read the terms of the marriage contract. If the marriage is not consummated there will be consequences. If the fault is Margaret’s, Norway will get back the Hebrides and the Isle of Man (ceded to Scotland in 1266). If the fault is Erik’s, Norway must cede Orkney to Scotland. So much depended on what Bart Simpson famously called ‘the bed stuff ’. As fate had it, however, neither of these political alternatives proved necessary. Erik impregnated Margareta when he was 14, but she died in childbirth. Their daughter Margaret, known in Scotland as the Maid of Norway, became Queen of Scotland at the age of 3 when her grandfather, Alexander III, riding between Edinburgh and Kinghorn on a misty night, fell from his horse over the cliffs and broke his neck, plunging Scotland into a period of chaos which the English Edward was not slow to exploit. Sent to Scotland at the age of 6 to take up her throne, the Maid died during a dreadful storm, and the vessel, pathetically laden with sweets for the pleasing of a tiny royal palate, put in to Orkney. Erik later married Isabella Bruce, the sister of Robert the Bruce. Typically though, it is not the politics that interest Mackay Brown. Drawn himself, he draws you too, irresistibly, into the human tragedy, reminding you as always that history is about people, about us, and that children are often the greatest victims of politics. The letters reflect the beauty of the man – one who came from a poor family and who spent much of his early life in the wilderness that was woven around him by tuberculosis and its consequent physical and social effects. It was in this wilderness that he discovered words – and realized that he had the gift to sow them and to make the desert blossom about him. Not that he would ever have put it so grandly, or so immodestly. ‘It was the one thing I was good at,’ he told me simply, ‘so it seemed to make some sense to use the talent.’ That humility kept him in Orkney, exploring his world – his chosen and only subject – and multiplying his talent. A bachelor, he was wedded to it, the world and the talent. I use the singular because, as Seamus Heaney once wrote, ‘his sense of the world and his way with words were powerfully at one with each other’, and the timeless simplicity of islands and sea, of their life-rhythms and work-patterns, are written into these letters as they were written into his voice, a soft lilting voice with something of the sea in it, something of his Gaelic-tongued mother, and lots of Orkney. And into his face too – the face of an old Viking. Under the tangled mop of waves breaking over a cliff-overhang forehead, the sunken eyes and cheeks revealed the years of illness. (Once I suggested to him that writing itself is a form of illness and he replied, ‘You’ve understood me.’) But the eyes were luminous, seeing through the simple surfaces of things to their hidden complexities, and the jutting jawbone was one which would have made even Ted Hughes retire from the field. You could have ploughed a field with it – ‘as Samson once did’, I ventured to joke with him. ‘But that was the jawbone of an ass!’ retorted George, correcting me and winking into his beer. ‘And he killed Philistines with it!’ George couldn’t abide Philistines or asses, especially pompous ones, and he shunned literary parties like the plague. Beer, television, books, a bunch of daffodils in the window, shopping for his simple needs with a battered old message bag and talking to all and sundry on the way – he liked and did the ordinary things. In one sense that was what made him so extraordinary, and something of that paradox may also be found in these letters. There was one letter that was permanently pinned to his front door every day between the hours of eleven and four. It was a letter addressed to the world and it said simply: ‘Back at 4.15’. Everybody knew it was a polite fiction for ‘Do not disturb, writer at work!’ And it became absolutely essential or him to do this. He’d grown tired of answering the knock on the door that would reveal fifteen bowing Japanese students and their professor, eagerly disembarked from the ferry without a word of warning, grinning greenly through their seasickness and with notepads and pens at the ready, all expecting an hour of illumination at the feet of the master. Women pursued him too – and once he even went into hiding: an awkward business in Orkney, where everybody knows everybody and you can hear the people next door changing their minds. As a young practitioner writer a quarter of a century ago, I popped my first story into an envelope and sent it off to Orkney to my literary hero, about whom I knew nothing outside his writings. A few days later there arrived a letter which I still treasure. He confessed that his heart sank every time the postman brought a brown envelope containing the manuscript of some trembling genius. On this occasion, though, his heart had lifted. And he asked me to come up to Orkney and have a gabble. A short time afterwards I ran into someone who had been a fellow-student of George’s when he’d studied literature at Newbattle Abbey under Edwin Muir, and I asked eagerly, ‘What’s he like?’ To my surprise he answered: ‘A man of enormous strength!’ ‘You mean spiritual strength, I suppose?’ I asked. ‘No, I mean physical strength.’ He then recounted the story of a night’s drinking in a famous poets’ pub in Edinburgh, at the end of which they’d rolled back to Newbattle and tried to put George to bed. ‘But the door to his room was surrounded by one of these old-fashioned cast-iron radiator pipes – it went all the way round the lintels and top – and while four of us held him like a battering-ram and tried to get him through, he got hold of this pipe with both hands and refused to let go – and could we get him off that pipe?!’ When I saw the frail-looking writer sitting in a rocking-chair and smiling at me mildly, I told him this story. He blushed a bit and said: ‘The days of my folly. I discovered words at Newbattle but I also discovered alcohol!’ You won’t find any revelations of that nature in these letters, but you will find many others, including recipes. Highland Park malt whisky, Orkney fudge and Atlantic crabs are some of the really good things that come out of the islands, and if you haven’t tried clapshot, or even heard of it, Mackay Brown’s account of how it put a glow in the wintry stomach one early February will have you rampaging through the kitchen to put it to the test. And I hope this enticement is enough to send you rampaging through the streets to the nearest bookseller. I have eaten clapshot at Mackay Brown’s table and I have tasted his words of wisdom. I am not going to give away any secrets. Read for yourselves.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 4 © Christopher Rush 2004

About the contributor

Christopher Rush was born in St Monans, Fife, and spent thirty years schoolmastering in Edinburgh. He wrote prolifically for a decade, fell silent for another, and has now returned to both writing and his sea-roots. His memoir about the death of his wife, To Travel Hopefully, will be published in January.