There’s a picture in The Third Ladybird Book of Nursery Rhymes of a small, nervous boy in knickerbockers appearing before a man of authority: ‘I do not like thee, Doctor Fell,/ The reason why, I cannot tell./ But this I know and know full well,/ I do not like thee, Doctor Fell.’ It’s a curious little thing, but somehow very pleasing. It rhymes, there’s a clear, easy rhythm behind the words and we’re familiar with the sentiment. In short, it’s a typical nursery rhyme.

I became interested in nursery rhymes when I was writing my last novel, When the Floods Came. The novel is set in the near future and I wanted a heritage for the children, something that would connect them – living in an otherwise empty tower block and surrounded by a crumbling, watery world – to their parents’ old life. A book of nursery rhymes provided the solution, with the words and pictures embedded in everyone’s memory, little gems of harmless nonsense that are reminders of the past, that link people from all ages and backgrounds. So I unearthed the three Ladybird Books of Nursery Rhymes that I’d read to my children. They were surprisingly familiar, almost as if they came from my own childhood, but the dates of publication – 1965, 1966, 1967 – make it clear that they didn’t. How interesting that they’ve remained with me for decades when they’re not mine at all. Now that I have rediscovered them, though, it worries me that they’re losing their place in our collective memory, marching down the hill with the Grand Old Duke of York and lacking the energy to march back up again. Do they still have a place alongside the electronic entertainment of today’s children?

But when I open them there’s something wrong. Some of the words that I remember are different from the ones in the books. How can this be? You’ve got it wrong, I want to say. My version is the only right one. Obviously! Could this be the result of regional pronu

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inThere’s a picture in The Third Ladybird Book of Nursery Rhymes of a small, nervous boy in knickerbockers appearing before a man of authority: ‘I do not like thee, Doctor Fell,/ The reason why, I cannot tell./ But this I know and know full well,/ I do not like thee, Doctor Fell.’ It’s a curious little thing, but somehow very pleasing. It rhymes, there’s a clear, easy rhythm behind the words and we’re familiar with the sentiment. In short, it’s a typical nursery rhyme.

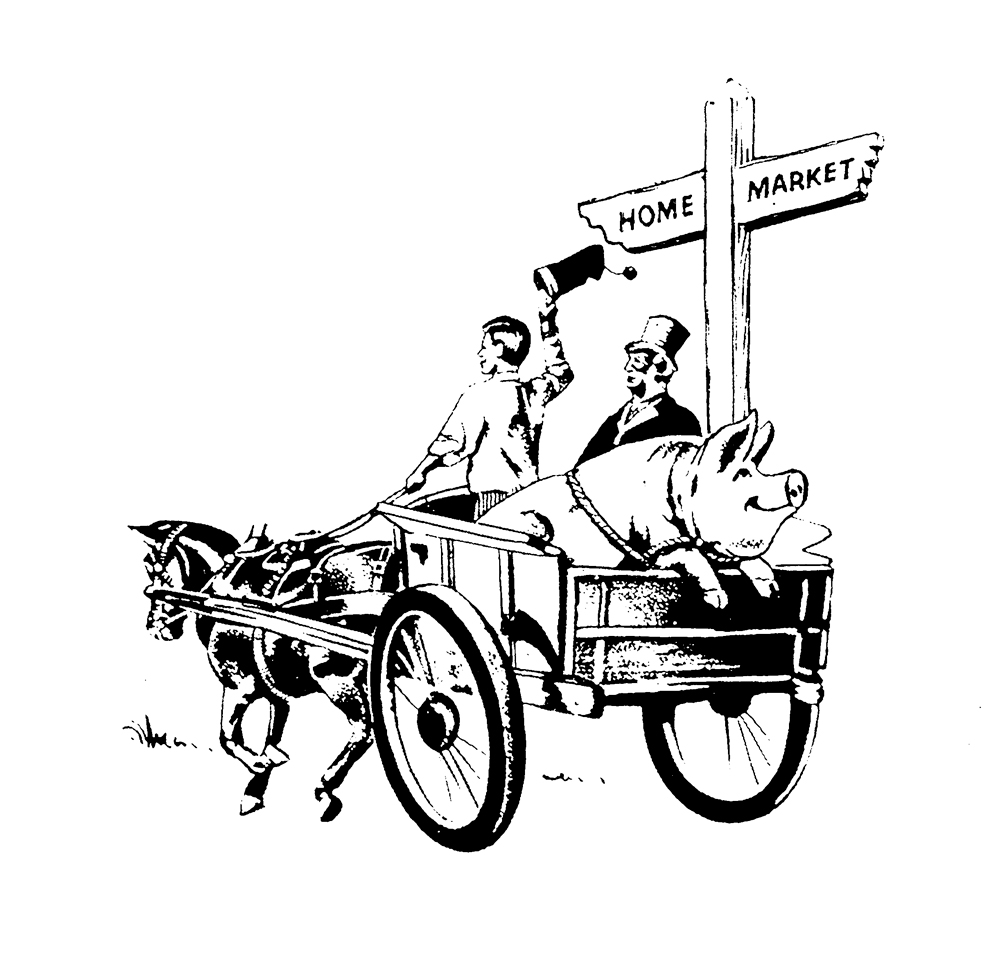

I became interested in nursery rhymes when I was writing my last novel, When the Floods Came. The novel is set in the near future and I wanted a heritage for the children, something that would connect them – living in an otherwise empty tower block and surrounded by a crumbling, watery world – to their parents’ old life. A book of nursery rhymes provided the solution, with the words and pictures embedded in everyone’s memory, little gems of harmless nonsense that are reminders of the past, that link people from all ages and backgrounds. So I unearthed the three Ladybird Books of Nursery Rhymes that I’d read to my children. They were surprisingly familiar, almost as if they came from my own childhood, but the dates of publication – 1965, 1966, 1967 – make it clear that they didn’t. How interesting that they’ve remained with me for decades when they’re not mine at all. Now that I have rediscovered them, though, it worries me that they’re losing their place in our collective memory, marching down the hill with the Grand Old Duke of York and lacking the energy to march back up again. Do they still have a place alongside the electronic entertainment of today’s children? But when I open them there’s something wrong. Some of the words that I remember are different from the ones in the books. How can this be? You’ve got it wrong, I want to say. My version is the only right one. Obviously! Could this be the result of regional pronunciation, perhaps, a change in emphasis? No, geography can’t alter rhythm. I imagine an editor making alterations, missing the point by never reading out loud, tone deaf in a rhythmic sort of way. It eventually occurs to me that the differences might be the result of my own mistakes. Who sang the rhymes to me in the first place? My parents? Teachers at school? Listen with Mother? I have no recollection. I just seem to know the words. It’s possible that I misheard them or changed them in my head, and then repeated the new version to my own children without reading the books properly. Perhaps this doesn’t matter at all and nursery rhymes are meant to be transient, variations on a theme. Although I’m still puzzled about the ones that don’t scan. They really don’t work without rhythm. There are sixty nursery rhymes altogether in the Ladybird series, twenty in each, and every page is crowded with cheerful images. On the cover of Book One, Little Bo Peep, dressed as a shepherdess (apparently based on the china figurines that old ladies used to keep in their glass-fronted, dark-wood cabinets), is peering into the distance from under her flowery bonnet, ignoring the sheep behind her; in the foreground, Humpty-Dumpty (in the uniform of a soldier) seems to have survived his fall and looks confused; next to him, a moustachioed dish is running away with the spoon, carrying a suitcase and looking hopeful; and a boy on a toy horse is heading for Banbury Cross in the background. Not bad for one cover. I start to wonder why it’s always considered necessary to illustrate the people in nursery rhymes with clothes and backgrounds from the past. Is everyone (including, apparently, children) yearning for a long-gone idyll where world annihilation had not yet been invented; a kind of golden age where women were plump and wore bonnets and had rosy cheeks, where girls had blonde ringlets and boys were dressed in lace collars and buckled shoes? Are the Victorians, apparently the inventors of childhood, whispering to us still? And why is Humpty-Dumpty always portrayed as an egg? There’s nothing in the rhyme to suggest anything more than a fatal accident. Does Lewis Carroll have something to do with this? It’s hard to pinpoint a specific period that is being represented in the Ladybird series – it’s not at all consistent. ‘Peter, Peter, pumpkin eater,/ Had a wife and couldn’t keep her’ has a medieval feel (something to do with the hats), but why does ‘As I was going to St Ives,/ I met a man with seven wives’ (which incidentally, I wouldn’t have identified as a nursery rhyme, more an old-fashioned riddle) have a carful of Barbie doll look-alikes, all seven of them dressed as if they’ve come straight out of 1950s Hollywood? It’s a curious picture, this one, with them all piled into an early twentieth-century car. One of the wives is playing with kittens on a canopy above the car while a man on a bicycle, a guitar on his back, challenges them. How did all this find its way into a tale about a journey to Cornwall? But Yankee Doodle (should this really have a place in a book of English nursery rhymes?) has all the right gear for a frontiersman – beaver hat, musket, British soldiers in the background – which dates it fairly accurately to the American War of Independence. It has to be said that not all the pictures are satisfactory. Little Polly Flinders warming her pretty little toes and ruining her nice new clothes, is endearing, whereas the image of Dr Foster falling into a puddle – a big fat man with a caved-in top hat, crossed eyes and enormous whiskers – is unlikely to induce a cosy glow of nostalgia in anyone who goes out in the rain, visits Gloucester or combines both activities. It’s more frightening than reassuring, despite its snappy rhythm. And what about the creepy man in ‘Goosey Goosey Gander’, wandering upstairs and downstairs and in my lady’s chamber, refusing to say his prayers? Are we supposed to cheer as we witness his head-first tumble over the banisters? Don’t we advocate fair trials any more? Is there sufficient evidence to prove his guilt? There are one or two that are less familiar: ‘The man in the moon came down too soon/ and asked his way to Norwich./ He went by the south and burnt his mouth/ by eating cold plum porridge.’ I wonder why he’s wearing flying goggles. It’s not as if they’d be much use once he left the atmosphere. But then he has apparently drifted down in a balloon. A certain lack of scientific expertise there, I would say. Although that could be the point. Reality is only for grown-ups.There was an old woman tossed up in a basket, Seventeen times as high as the moon; Where she was going I couldn’t but ask her, For in her hand she carried a broom. Old woman, old woman, old woman, quoth I, Where are you going to up so high? To brush the cobwebs off the sky! May I go with you? Yes, by and by.I like this one but can’t explain why the image of a woman brushing cobwebs off the sky pleases me more than an unlikely astronaut who’s worrying about his breakfast. It can’t be the pictures. The man in the moon is distinctly odd, but the woman with the broom has a very alarmed child with her and her smile is deeply sinister. I’m not sure that it matters. Despite their oddness, the pictures bring back the words, demand that I chant them out loud. I’ve heard, many times, that there’s a deeper meaning to these rhymes. ‘Ring-a-Ring-a-Roses’, for example, was thought to have originated with the Black Death. It seems, however, that not everyone agrees with this interpretation and folklorists no longer attach significance to the words. I’m with them on this. These are not like fairy tales, dark and sinister, grappling with good and evil. Most of them are simple tales invented by ordinary people who wanted to introduce some fun into their lives. I like the idea of parents, grandparents, an uncle crippled with arthritis who live in a crooked house, sitting with their little ones and watching the world go by, finding a nice phrase, repeating it, establishing a rhythm and spinning it all into a neat little rhyme. ‘Jack be nimble, Jack be quick, Jack jump over the candlestick.’ Say the words out loud, click your fingers. It has a rhythm and it has a beat. Do we care if it doesn’t mean anything? So are these Ladybird books works of art or clumsy renditions that have no serious research behind them? Now that I’ve studied the pictures more closely, I have to conclude that they are not the work of an unacknowledged genius. Like the words, they are little more than gentle nonsense. Some are executed crudely (especially the ones with soldiers or sailors, and there are quite a few of those), but who can resist Little Jumping Joan, all alone, high in the air, mid-jump, her hair flying out behind her, caught in a stage spotlight? The lack of historical consistency is unnerving but probably irrelevant because they do their job. They place themselves in our memories. So the words and the images are harmless but somehow significant in the process of growing up. We’re familiar with the physical evidence of heritage, rooted in landscape and buildings, watched over by organizations like the National Trust, but we must remember to preserve our personal memories too, the experience of childhood that links us to long-gone generations. Our world seems to be shifting into a faster gear, whizzing past landmarks before we can see them clearly, moving on to the next wonder. There’s no appetite for spare parts any more, mending or making do, no time to sit and look backwards while playing with words. Are we losing our sense of permanence? We shouldn’t allow ourselves to become like those three blind mice, unaware as the farmer’s wife creeps up behind them with her carving knife. Let’s keep our tails intact, protect them, keep them safe.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 65 © Clare Morrall 2020

About the contributor

Clare Morrall is a novelist and music teacher who lives in Birmingham. The most recent of her eight novels is The Last of the Greenwoods. Nursery rhymes play a significant part in her seventh novel, When the Floods Came.