The food writer Theodora FitzGibbon was a late beginner, professionally speaking. Born Theodora Rosling in 1916 she received a cosmopolitan education, travelling widely in Europe and Asia with her Irish father Adam, a naval officer and bon viveur afflicted with wanderlust as well as a wandering eye. Theodora had a number of siblings conceived on the wrong side of the blanket. He also introduced his daughter to the delights of whiskey and cigars at a perilously early age. Later, in her teens, she began to forge a career as an actress on tour and in the West End, while her imperious good looks also helped her find work as a fashion model for some of the best-known couturiers of the day. (An old wartime film called Freedom Radio, about German resistance to the Nazi regime within the Third Reich, features the young Theodora Rosling in a cameo part, and is a rattling good yarn into the bargain if you’re lucky enough to find it.) It was not until she was in her mid-thirties that she wrote her first cookery book but she went on to produce at least two dozen more.

It is a sad and to me inexplicable fact that even in her own lifetime much of Theodora’s work was eclipsed by that of her contemporaries Elizabeth David and Jane Grigson. Her output was impressive, especially the A Taste of . . . books, a series she devised with her publisher Dent, starting with Ireland as the first title in 1968.

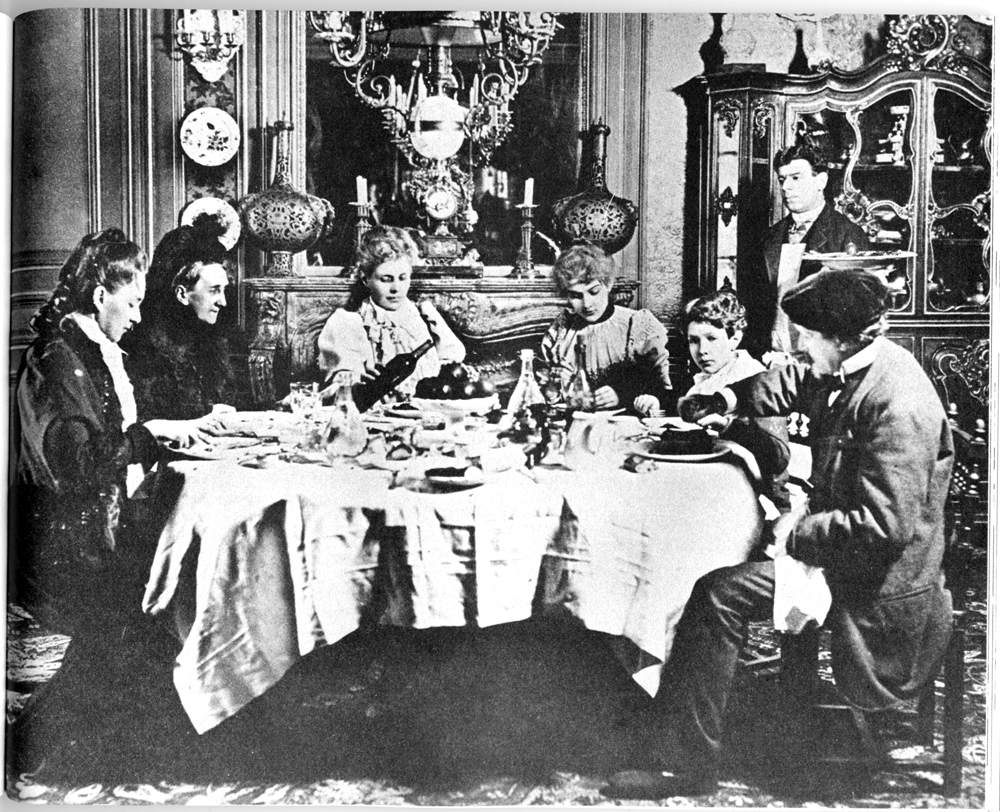

The concept proved a winner, with recipes, history and anecdotes on one page and wonderful black-and-white photos – many of them well over a century old – on the facing page. In A Taste of Paris (1974), for example, the sixth in the series, gigot au pastis is accompanied by a picture of the semi-comatose Verlaine somewhere in Montparnasse with a generous half-pint of absinthe on the table in front of him. Finding the illustrations for the books in the series, incidentally, was the work of Theodora’s second husband George Morrison, whom she married in 1960 after divorcing the Irish-American writer Constantine FitzGibbon.

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inThe food writer Theodora FitzGibbon was a late beginner, professionally speaking. Born Theodora Rosling in 1916 she received a cosmopolitan education, travelling widely in Europe and Asia with her Irish father Adam, a naval officer and bon viveur afflicted with wanderlust as well as a wandering eye. Theodora had a number of siblings conceived on the wrong side of the blanket. He also introduced his daughter to the delights of whiskey and cigars at a perilously early age. Later, in her teens, she began to forge a career as an actress on tour and in the West End, while her imperious good looks also helped her find work as a fashion model for some of the best-known couturiers of the day. (An old wartime film called Freedom Radio, about German resistance to the Nazi regime within the Third Reich, features the young Theodora Rosling in a cameo part, and is a rattling good yarn into the bargain if you’re lucky enough to find it.) It was not until she was in her mid-thirties that she wrote her first cookery book but she went on to produce at least two dozen more.

It is a sad and to me inexplicable fact that even in her own lifetime much of Theodora’s work was eclipsed by that of her contemporaries Elizabeth David and Jane Grigson. Her output was impressive, especially the A Taste of . . . books, a series she devised with her publisher Dent, starting with Ireland as the first title in 1968. The concept proved a winner, with recipes, history and anecdotes on one page and wonderful black-and-white photos – many of them well over a century old – on the facing page. In A Taste of Paris (1974), for example, the sixth in the series, gigot au pastis is accompanied by a picture of the semi-comatose Verlaine somewhere in Montparnasse with a generous half-pint of absinthe on the table in front of him. Finding the illustrations for the books in the series, incidentally, was the work of Theodora’s second husband George Morrison, whom she married in 1960 after divorcing the Irish-American writer Constantine FitzGibbon. Coq au vin was the first dish I cooked from A Taste of Paris and perhaps my first serious attempt at French cuisine. It’s not difficult: braising meat is a relatively easy and forgiving process for a beginner. I used to follow that with Theodora’s parfait au chocolat, simplicity itself if you follow her instructions to the letter and a glutton’s delight. So I owe A Taste of Paris an enormous debt for initiating me into the rudiments and refinements of French cooking, though there was another influence that was to prove equally strong in time. Traiteurs are to be found all over France, often as part of a butcher’s shop or charcuterie. They sell cooked dishes ready for the lazy gourmet to heat through at home: duck à l’orange,blanquette de veau, ham with Madeira sauce and a hundred other delights. The best cook I ever knew was Annie Roget, married to Pierre whose butcher’s shop was across the road from where we lived in Paris near the Bastille. Each morning she prepared the most wonderful dishes for lunch that only cost a few francs per portion: in the afternoon she would often have to look after the butcher’s shop alone while her husband could be found slumped in a Verlaine-like stupor in front of one of his carcasses after a liquid lunch at the bar next door. There was also a little bistro round the corner in the rue Keller, an old-fashioned eating-house (very similar, incidentally, to the one facing Theodora’s recipe for blanquette de veau with its frowsy workmen posed on classic café chairs), whose regular customers kept their napkins in numbered pigeon-holes by the door and whose mouth-watering three-course lunches were renowned throughout the neighbourhood. Every morning as I stared out of my attic window I would see the patron trotting off to market with his shopping-basket on wheels. Braised rabbit with prunes was a favourite in the rue Keller and Theodora’s recipe hits the spot precisely, though it should be remembered that in France plump and tender farmed animals are used rather than their lean, athletic and wild cousins that we cook in England. When I first went to live in Paris entertaining friends was a little daunting. Our apartment remained a building site for almost a year, but we enjoyed the hospitality of our friend Pépo who had a vast one-roomed studio all to himself across the courtyard. Dinners there were enormous fun, though our shopping had to be carefully planned – as yours would be too if you had to carry it up ninety-seven stairs. Sometimes we’d have a rest on the way up and put the shopping down, especially if it had bottles in it. Theodora’s pot-au-feu proved an infinitely expandable dish that could feed up to a dozen friends on a Saturday night. (The author cannily includes the advice to throw away the vegetables used in cooking and add fresh ones half an hour or so before serving.) The only problem chez Pépo was the WC, which was not in a room by itself but right next to the dining-table, peeping coyly out from behind a potted plant, ignored at first but eventually used by everybody. Although A Taste of Paris is a working cookbook, it has some real rarities among the more traditional classic fare: its author casts a wide net and expresses her determination not to limit her attention to the flashy showpieces of haute cuisine. Only this afternoon while I was writing this my wife picked the book up and baked a batch of petits marcellins, crunchy little almond pies with rum in the pastry and cointreau in the filling, the like of which I’ve never tasted before. Theodora’s formula for a foolproof pain de campagne is another godsend (and the perfect vehicle for mopping up the juices of the Marquise de Valromey’s civet de lièvre, my own personal favourite in the collection). Recipes apart, the book’s chief delight lies in those pictures which linger in the mind. An image of the immortal Sarah Bernhardt snatching forty winks in the coffin in which she habitually slept is not easily forgotten. Another is a vividly evocative sepia photo circa 1882 of a working girl’s bed-sitting room heated by a simple coke stove, with a pot on top which supplied her hot water and was used to cook her nightly dinners. According to the first volume of her autobiography, when Theodora arrived in Paris as a young actress in 1938 and met the first great love of her life, the artist and photographer Peter Rose Pulham, they seem to have lived in a very similar room with very similar facilities. Money was short and food was prepared on a home-made arrangement of wire in the fireplace. But it was there that she began seriously to learn to cook. One of her first successes was braised beef and carrots (boeuf à la mode) for which her recipe is included in the book and which I served up for a wedding breakfast at a Paris artist’s studio in 1989. This is a dish better eaten cold, and since I was doubling as best man for the occasion it seemed ideal. To serve it up with sautéed potatoes I had the unsolicited assistance of a small boy, the bride’s son, and with his over-enthusiastic help it was but a matter of minutes before the gauze curtains at the window caught fire. Flames were soon dancing up to the ceiling and only the miraculous arrival of the fire brigade prevented the wedding from morphing into a funeral. Eventually we all sat down round a rather damp table and I sliced up the shining log of beef and carrots in its golden jelly but the fun had gone from the celebration. I was no longer the best man, I was in disgrace, and I have never felt tempted to cook boeuf à la mode again.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 66 © Clive Unger-Hamilton 2020

About the contributor

Clive Unger-Hamilton worked in restaurants in London and France before he and his wife opened the first fish-and-chip shop in Paris in 1987.

This is just to say

that Unger-Hamilton’s baroque

flavours the ingredients with tart

that is as good as a feast