In 1992, I started working for a strange but beguiling organization. The Royal Society of Literature was, in those days, housed in a huge, dilapidated mansion in Bayswater, and it was there that its Fellows gathered to raise a farewell glass to my predecessor. They were an elderly, rather moth-eaten bunch, but one stood out – a strikingly handsome younger man in a velvet jacket. Somebody introduced me: ‘This is Colin Thubron. He’ll be a great support to you.’

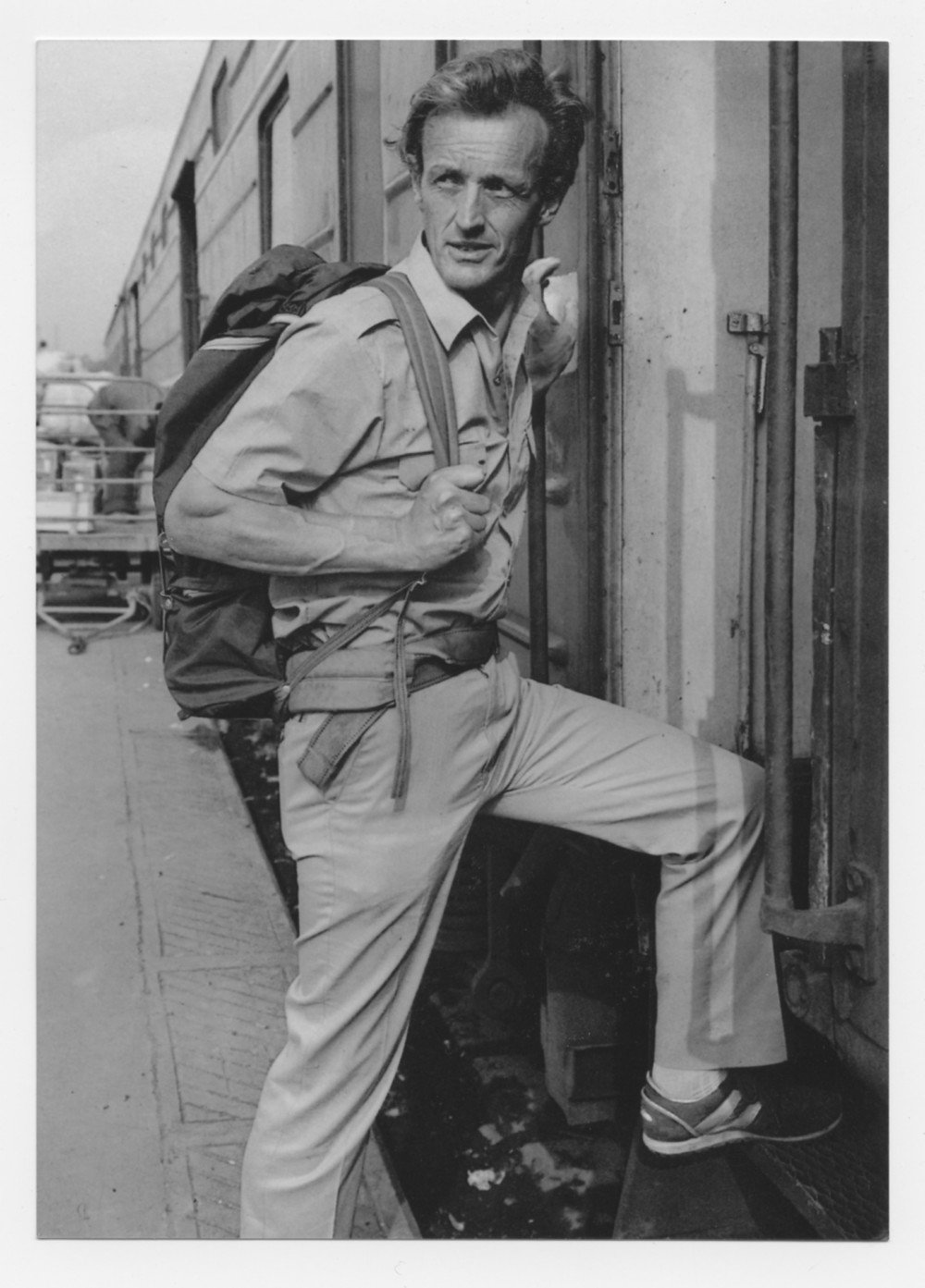

And so he proved – when he was in London. For great tracts of time he was away, leaving his ‘old self behind’, exploring places most of us would neither dare nor desire to visit, but which we love to read about with a vicarious sense of fearlessness and endurance. In the golden generation that produced Jonathan Raban, Bruce Chatwin, Paul Theroux and Redmond O’Hanlon, Thubron is now the Grand Old Man, bringing to journeys that are physically and psychologically testing a fine, romantic sensibility. Even when there is apparently nothing to describe, his prose is seductively beautiful: ‘A traveller needs to believe in the significance of where he is, and therefore in his own meaning,’ he writes in In Siberia (1999), as he chugs by train towards the Arctic Circle. ‘But now the earth is flattening out over its axis. The shoreline is sinking away. Nothing, it seems, has ever happened here.’

We meet on an autumn morning, sun streaming through the French windows of Thubron’s elegant Holland Park drawing-room. We sit in deep, white sofas, eating biscuits. Surely Thubron, now 79, can’t want to leave all this behind and subject himself to the challenges and privations of another three-month journey? Yes, he says. He does. He is preparing himself to travel down the Amur, the ninth longest river in the world. It runs between Russia and China, so he is brushing up the Russian and Mandarin he learned for Among the Russians (1983) and Behind the Wall (1987). He is also playing regular games of tennis with his Russian tutor, to keep fit – ‘although I’ve been rather lucky on that score: I’ve been fit all my life’.

One might expect him also to be building up lists of contacts – people to track down and interview when he arrives. But no. ‘What I’m looking for, when I travel, is people in their context. In China, for example, I don’t want somebody giving me information about the Cultural Revolution, I want somebody to tell me what they suffered in it. The people I’m speaking to are mainly working-class, they’re farmers or petit bourgeoisie. Meeting them depends on serendipity, and I like that.’

It also depends on Thubron planting himself in some pretty grim places – fifth-class railway carriages stinking of sweat and urine, aisles awash with cigarette ash and phlegm; rat-infested hotels; cafés serving stomach-churning food. Travelling through China, he often had no idea where the next meal was coming from. And when an opportunity to eat presented itself, a menu might read like this: ‘Steamed Cat, Braised Guinea Pig (whole) with Mashed Shrimps, Grainy Dog Meat with Chilli and Scallion in Soya Sauce, Shredded Cat Thick Soup, Fried Grainy Mud Puppy . . . Braised Python’. In Siberia, of all the meals he describes, the most palatable is ‘pony in a cream mushroom sauce’.

As he travels, weight drops off him, he becomes physically depleted, he comes close to breaking-point. But he has never been tempted to give up. ‘I don’t tend to be worried on a physical level – and in a way the more extreme things become, the more exciting they are.’ In fact, he feels a duty to his readers to expose himself to danger. During his 6,000-mile journey through Siberia, he made a spur-of-the-moment decision to climb aboard a ‘damn great cargo boat’ and ask to be dropped off at the remote, benighted village of Potalovo. He was warned against it: its Entsy inhabitants were, almost to a man, ne’er-do-wells and drunks, frequently violent. The only sympathetic character Thubron met was a doctor, marooned Ben Gunn-like in this bleak outpost, and sustained by just two books: a pocket edition of Kipling’s poems and A Thousand English Jokes. Nobody could say when the next tanker might pass by to return Thubron to relative civilization. He could have been there for months.

You do these things that are perhaps a little extreme, like stopping off at Potalovo (people said, ‘Don’t! You’ll be knifed!’) and you think, ‘Should I, or shouldn’t I?’ The first thought is, ‘I don’t want to be knifed.’ But the second is what good copy it will provide. And the third is that if you don’t do it, you are letting down your book, and letting down the culture. You’re refusing to see an integral and important part of the country you’re travelling in. You’ve lapsed in your responsibility. So often the things you are hesitant to do yield something really good.

Certainly the pages on Potalovo in In Siberia make for grimly compulsive reading.

In recent months, Thubron’s time has been taken up with reading scores of novels as a judge for the Man Booker Prize. But now that this is over, and he can devote himself to reading up about the Amur, he is longing to be off. ‘The more I research, the more I’m itching to go. The more I can see the shape of the journey, the more excited I get.’ But as he gears up there are two things that cause him apprehension. ‘I do worry about bureaucracy, the police, oppression from above rather than chaos from below.’

In the Soviet Union, in the 1980s, he was followed by the KGB who confiscated all his notes (his writing looks as if an army of tiny ants, dipped in ink, has danced all over the pages: the KGB, baffled, gave him the benefit of the doubt and handed them back). Amur is a ‘political river’. He fears it might get nasty again. And then he fears ‘sterility’ – not finding people who will talk to him. Over the years, he has developed techniques to combat this. He seeks out places where people won’t easily be able to escape him. In China, for example, he followed a man into a public bath house, and stripped off all his clothes: ‘I had an idea that the stripping off of clothes might strip away mental barriers too.’ One by one, naked Chinese men began to speak to him.

Often, though he knows what he wants to find out from someone, instinct tells him that to ask direct questions won’t work. ‘So one thing I do is to expose myself a bit too. Then it’s as if you’re both going downhill, and you’re preceding them in giving yourself away. You tell them you too have a terrible time with your income, or you’ve had a row with your wife. You let them feel it’s OK to expose themselves on that level.’ Crucial to this is the fact that Thubron is always travelling alone: ‘If you’re on your own, you’re the oddity, and you are forced into understanding other people. I like to think I’m transparent. Of course I’m not. I carry my culture around like a pilgrim’s sin on my back . . .’

Hand in hand with these ploys goes exceptional charm. Thubron is not just handsome but empathetic and instantly likeable. People relish his company. As the biographer Victoria Glendinning says, ‘When Colin walks into a room you think GOOD!’ In his first book, Mirror to Damascus (1967), even a Mother Superior opens the doors of her convent and invites him to stay among her nuns.

So how did it all begin? ‘The love of words came before the love of travel. I was in love with words from the age of about 8,’ says Thubron, ‘doubtless influenced by my mother’s connection with John Dryden: he was her collateral ancestor.’ But, well into his teens, he saw a future for himself as a poet and novelist. Then, when he was 19, his sister – and only sibling – Carol was killed in a skiing accident.

His parents took him on a long holiday in the Middle East ‘as a way of escaping sadness’. Somewhere near Damascus, their camper van broke down. Mr and Mrs Thubron stayed put, but Colin took himself into the city to explore. ‘I became fascinated with urban culture – with the history and the architecture. I would walk about peering through doors that had been left open, looking through to marble- and basalt-paved courtyards with lemon trees and fountains. It was a world sufficiently attached to what I knew – it had a relevance to European history – but also exotic and strange.’ The idea of travel writing took root. Was it an escape? ‘Absolutely not. For me, staying at home is much more to do with escape.’

Thubron’s wife, Margreta, is unfazed by his lengthy absences from home, and by the fact that, when he sets off for the Amur river, he won’t be taking a mobile phone. And when he returns, she will give him space as he works ‘with a slightly crazy stamina’, turning his notes into a book. Margreta is a Shakespearean scholar, ‘and she too works long hours and very intensely. She’s not in the background wanting to go to a party, or a play. So we just turn down invitations and work solidly from 9 to 9.’

Though few could match Thubron for courage, perseverance, intelligence and sensitivity, it’s hard not to think that his has been a charmed existence. But much has changed since he set out as a travel writer half a century ago. Damascus, the city that first fired his imagination, and where he found the people ‘intoxicatingly hospitable to this naïve and enthusiastic young man’, has been transformed by war, and by the crises that have afflicted the Middle East during the last fifty years – ‘the conflicts with Israel, the eclipse of war-torn Beirut, the impact of the Arab Spring’. And every part of the world has come under the homogenizing influence of Westernization. How does he respond when, as sometimes happens, a young person confesses that he too longs to be a travel writer?

‘One would have to say it would be difficult,’ Thubron deliberates,

especially if he was serious, by which I mean if he was a writer as well as a traveller (a traveller who just does a tough voyage has never much interested me). But at the same time the fact that the world appears to be getting smaller and more accessible is to some extent an illusion. The world is known, but only superficially. The Westernization of the world is a superficial thing. Cultures are tremendously resilient, and the future of travel writing is in stripping away the apparent accessibility and Westernization and finding what’s distinctive underneath. It’s all still there, sitting there, waiting.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 58 © Maggie Fergusson 2018

About the contributor

Maggie Fergusson is Literary Editor of The Tablet, and Literary Director of the Royal Society of Literature.

Definitely unique. Mind boggling, dangerous hour use! But in the Amur River, did Colin have a sojourn in Russia, go to England for six months & return in May to finish his journey?