The huge literature on Winston Churchill can seem impenetrable to the casual reader. Churchill’s own writings, with their stentorian prose, do not always appeal (though My Early Life scores through its pell-mell pace of events). Martin Gilbert’s official biography marshals the main themes superbly but cannot convey the everyday feel of Churchillian life. A host of Churchill’s contemporaries have gone into print, reporting their dealings with the great man and basking in the light of his genius. Among them is Lady Violet Bonham-Carter, whose Winston Churchill as I Knew Him describes with beguiling insight her friend’s life up to the year 1916. In the preface Bonham-Carter quotes Gray’s remark to Horace Walpole: ‘Any fool may write a most valuable book by chance, if he will only tell us what he heard and saw with veracity.’ Such a man – though certainly no fool – was John (or Jock) Colville, one of the private secretaries to Churchill in both his spells as Prime Minister. During those periods Colville kept detailed diaries of events, which were published in 1985, two years before their author’s death, as The Fringes of Power: Downing Street Diaries, 1939–1955.

When Churchill acceded to power in 1940, Colville was an impetuous young man of 25. To keep a written account in wartime, as he did, was to take one hell of a security risk. Even now one shudders at the thought of certain entries getting into the wrong hands (‘The Cabinet are considering, very secretly, the possibility of bombing the Ruhr’, Nov. 1939). Colville left the forbidden record locked in a drawer of his writing-table at 10 Downing Street; then, stricken by conscience, began moving it to his family home in Staffordshire, because ‘its indiscretions were considerable’. Had he been rumbled it would have meant instant dismissal. He was amused to be told years later that the punishment for diary-keeping under Stalin’s regime was dea

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inThe huge literature on Winston Churchill can seem impenetrable to the casual reader. Churchill’s own writings, with their stentorian prose, do not always appeal (though My Early Life scores through its pell-mell pace of events). Martin Gilbert’s official biography marshals the main themes superbly but cannot convey the everyday feel of Churchillian life. A host of Churchill’s contemporaries have gone into print, reporting their dealings with the great man and basking in the light of his genius. Among them is Lady Violet Bonham-Carter, whose Winston Churchill as I Knew Him describes with beguiling insight her friend’s life up to the year 1916. In the preface Bonham-Carter quotes Gray’s remark to Horace Walpole: ‘Any fool may write a most valuable book by chance, if he will only tell us what he heard and saw with veracity.’ Such a man – though certainly no fool – was John (or Jock) Colville, one of the private secretaries to Churchill in both his spells as Prime Minister. During those periods Colville kept detailed diaries of events, which were published in 1985, two years before their author’s death, as The Fringes of Power: Downing Street Diaries, 1939–1955.

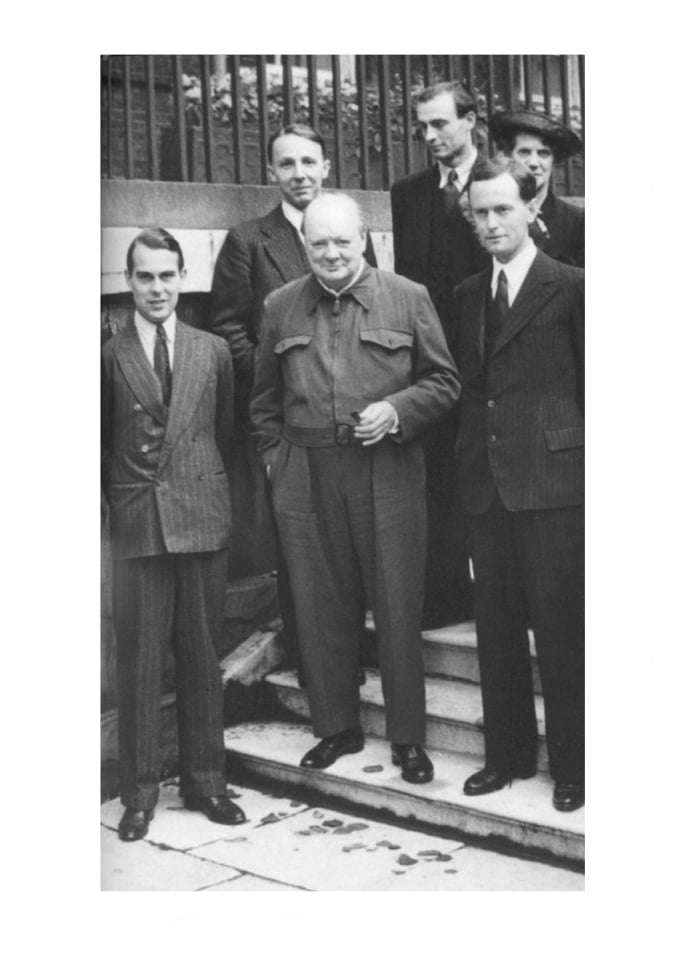

When Churchill acceded to power in 1940, Colville was an impetuous young man of 25. To keep a written account in wartime, as he did, was to take one hell of a security risk. Even now one shudders at the thought of certain entries getting into the wrong hands (‘The Cabinet are considering, very secretly, the possibility of bombing the Ruhr’, Nov. 1939). Colville left the forbidden record locked in a drawer of his writing-table at 10 Downing Street; then, stricken by conscience, began moving it to his family home in Staffordshire, because ‘its indiscretions were considerable’. Had he been rumbled it would have meant instant dismissal. He was amused to be told years later that the punishment for diary-keeping under Stalin’s regime was death. Seventy years on, posterity can only feel gratitude to the young Colville for taking such risks. And because, over the 800 pages of the published volume, he punctiliously eschewed making retrospective changes to the original entries, they now read like red-hot journalism rather than history. For in history – as Colville observed in 1944 – every event ‘gains or loses colour and accuracy if described after the passage of time’. Colville was a character. Martin Gilbert said so in his delightful book In Search of Churchill, highlighting the people who had helped with the official biography. Gilbert admitted to being ‘somewhat afraid’ of the then middle-aged martinet, always impeccably dressed, and with a low opinion – frequently expressed – of historians (‘You people almost never get it right’). Though not wealthy, Colville was extraordinarily well-connected: a grandson of the Marquess of Crewe, and in his youth a confidant of Queen Mary. ‘I do not think there was a single aristocratic family, however minor,’ Gilbert wrote, ‘that he did not know enough about to correct any conceivable error I might make.’ We learn a lot about the aristocratic lifestyle as the young Colville – in between his official duties – rides in Richmond Park, hunts, dances at the Savoy, plays croquet with Lady Churchill. And eats and drinks (in wartime!) with all the gusto of a man who was officially employed by the diplomatic service (oysters and champagne at Prunier’s, 15 Nov. 1940; sherry and smoked-salmon sandwiches at Diana Quilter’s First Aid Post, 31 Mar. 1941; even, ‘lunched admirably’ while flying over Casablanca, 14 Jan. 1944). It was an era when ladies withdrew from the table after dinner and Colville, though susceptible to the opposite sex, could not take them seriously: ‘It is a waste of time, and exasperating, to talk to most women on serious subjects.’ Nevertheless he dined frequently with men and women, for here was someone who embraced networking before the term was invented. Whatever else readers skip in these diaries it should not be the footnotes which, appearing on almost every page, pithily sketch a roll-call of characters: Mrs Richard Norton, the ‘deeply cherished friend and mistress of Lord Beaverbrook’; Lady Mary Glyn, ‘a rather trenchant and occasionally quite interesting relic of another age’; Eddie Marsh, ‘an aesthete with a prodigious memory [who] spoke in a high-pitched squeaky voice’. Reading Colville, we discover the war all over again. We feel anxiety about an imminent invasion of Britain. We meet new characters (‘There is apparently a young French General called de Gaulle’). We share the confusion and disbelief when a plane containing Rudolf Hess drops from the sky. The entries often relate great events to more personal details: ‘As I dismounted the groom told me that Holland and Belgium had been invaded’; ‘News that Paris has fallen. I am still reading War and Peace’; or, as Colville stays with relatives:These are the diaries of a young man. ‘There must be something wrong with me,’ Colville writes in April 1940, for ‘I just cannot take it tragically or feel nearly as depressed as I ought.’ The following year we find him reading Pepys, and are struck by the similarities to his famous (and similarly youthful) predecessor: the curiosity, intelligent observation of events, turn of phrase, humour – and most of all the sheer enjoyment of life. As with Pepys, we forgive the diarist’s little foibles and rejoice in his qualities. For all those qualities, it is Churchill’s personality that dominates the book. ‘The P.M.’s absence makes an astonishing difference,’ Colville notes in August 1941, and when the great man is missing from diary entries it is as if the blackout has extinguished all the lights of Downing Street. Fortunately Colville is usually Boswelling away by his leader’s side – watching, listening, and then recording in a multitude of situations: Churchill with family, friends and colleagues; Churchill on the Queen Mary, or inspecting damage from the Blitz, or watching allied troops crossing the Rhine; Churchill walking and talking under the stars and demonstrating arms drill with his big game rifle; Churchill at mealtimes, dictating in bed, prostrate on the floor at Chartwell, or in his bath being briefed by Colville (with intermissions for submersions). ‘When the women had gone to bed, I listened in the Great Hall to as interesting a discussion as I ever hope to hear,’ Colville records, sitting in on meetings with the US envoy Harry Hopkins. Churchill ‘talked of the past, the present and the future . . .’ And we, his fortunate readers, can eavesdrop on everything that is said. Colville also has a knack of setting scenes visually:During the afternoon an enemy raider surprisingly descended from the clouds and dropped eight bombs nearby – one hitting a train full of chocolate. Aunt Celia upset a silver kettle of scalding water over Lady Graham, but this was not cause and effect.

At dinner, Churchill’s conversation would mix state affairs with more playful topics:Went up to the P. M.’s bedroom at about 10.00 . . . He was lying in bed, in a red dressing-gown, smoking a cigar and dictating to Mrs Hill, who sat with a typewriter at the foot of the bed . . . His black cat Nelson . . . sprawled at the foot of the bed and every now and then Winston would gaze at it affectionately and say ‘Cat, darling.’

It is especially intriguing to gaze over Colville’s shoulder as Churchill prepares speeches and other communications. ‘To watch him compose some telegram or minute for dictation is to make one feel that one is present at the birth of a child’; and ‘Before dictating a sentence he always muttered it wheezingly under his breath and he seemed to gain intellectual stimulus from pushing in with his stomach the chairs standing around the Cabinet table.’ Later on Colville observes: ‘It is curious to see how . . . he fertilises a phrase or a line of poetry for weeks and then gives birth to it in a speech’; then ‘I followed the speech from a flimsy of the P. M.’s notes, which are typed in a way which Halifax says is like the printing of the psalms.’ Because the war’s big events are already known, the accounts of Churchill’s behaviour often fascinate more. That he was not easy to work for is a recurring motif. He was completely unpredictable, and inconsiderate with his staff ’s time. He would become hung-up on trivialities, as when he minuted the First Lord of the Admiralty urging the purchase of a new flag. His anger ‘was like lightning and sometimes terrifying to see’, though if it was unjust he ‘seldom failed to make amends, not indeed by saying he was sorry but by praising the injured party generously for some entirely disassociated virtue’. Even so, the constant factor in relations with colleagues was the ‘respect, admiration and affection that almost all those with whom he was in touch felt for him despite his engaging but sometimes infuriating idiosyncrasies’. The second part of the diaries, covering Churchill’s peacetime stint as Prime Minister (1951–5), is more spasmodic and less engaging than the first. Colville himself, no longer single, has lost some of youth’s brio. (‘Though marriage is an honourable estate, it is seldom a tonic for diarists unless they behave like Pepys.’) And Churchill is more grievously affected by the passage of time, as his private secretary does not shrink from recording. ‘On some days the old gleam would be there . . . the sparkle of genius could be seen in a decision, a letter or a phrase’; but ‘he was reluctant to read any papers . . . or to give his mind to anything that he did not find diverting . . . more and more time was given to bezique and ever less to public business.’ There is sadness but also an unmistakable sense of relief as the greatest living Englishman is eventually prised from office. Rather than end on this doleful note, let us revisit Violet Bonham-Carter, recording her first meeting with the 32-year-old Churchill at a dinner in 1906, nine years before Colville was born. Churchill ‘burst forth into an eloquent diatribe on the shortness of human life, the immensity of possible human accomplishments . . . in a torrent of magnificent language . . . and ended up with the words I shall always remember: “We are all worms. But I do believe that I am a glow-worm.”’ This remark presaged the events we are privileged to witness through John Colville’s diaries.As a less serious epilogue, the P.M. discoursed on egalitarianism and the White Ant. He recommended Lord Halifax to read Maeterlinck. Socialism would make our society comparable to that of the White Ant. He also gave an interesting account of the love life of the duck-billed platypus.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 35 © David Spiller 2012

About the contributor

David Spiller has twice kept diaries, which will never see the light of day.