Coming to the end of a really good book can pitch you into a slough of despond. This happened to me again recently when I finished The Pickwick Papers for the umpteenth time. Even though I know the novel well, I still have a sense of loss on reaching the final page.

Left wanting more Victorian sparkiness, I wondered where next to turn. The Pickwick Papers is unique in its pace and optimism – G. K. Chesterton said it was ‘something nobler than a novel’, carrying ‘that sense of everlasting youth – a sense of the gods gone wandering in England’. Superb though Dickens’s later works are, there is in them that encroachment of increasing gloom and disenchantment that is almost entirely absent from Pickwick.

So who, then? Trollope? Not really a thigh-slapper. Thackeray? Possibly. A dose of Becky Sharp or Pendennis might well do the trick. But then I have it: Cuthbert Bede. Well, the Reverend Edward Bradley writing as Cuthbert Bede. I first happened across him while mining the rewarding and delightfully chaotic depths of a West Country bookshop. He has been out of fashion for a considerable time, always a recommendation as far as I’m concerned, but I think his series beginning with The Adventures of Mr Verdant Green deserves to be regarded as a mid-Victorian comedy classic.

In a space barely two feet wide between packed shelves, I managed to prise out a dusty 1855 sixth edition. I opened it and discovered a whole new pleasure. At the beginning of Chapter 1, ‘Cuthbert Bede MA’ suggests his readers consult ‘the unpublished volume of Burke’s Landed Gentry’ to learn a little about the Green family. There follows a long list of mishaps, including various forms of financial ruin and the death of a Green blown up in his laboratory ‘when just on the point of discovering the elixir of life’.

We quickly deduce that despite having a documented lineage stretching back to 1096,

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inComing to the end of a really good book can pitch you into a slough of despond. This happened to me again recently when I finished The Pickwick Papers for the umpteenth time. Even though I know the novel well, I still have a sense of loss on reaching the final page.

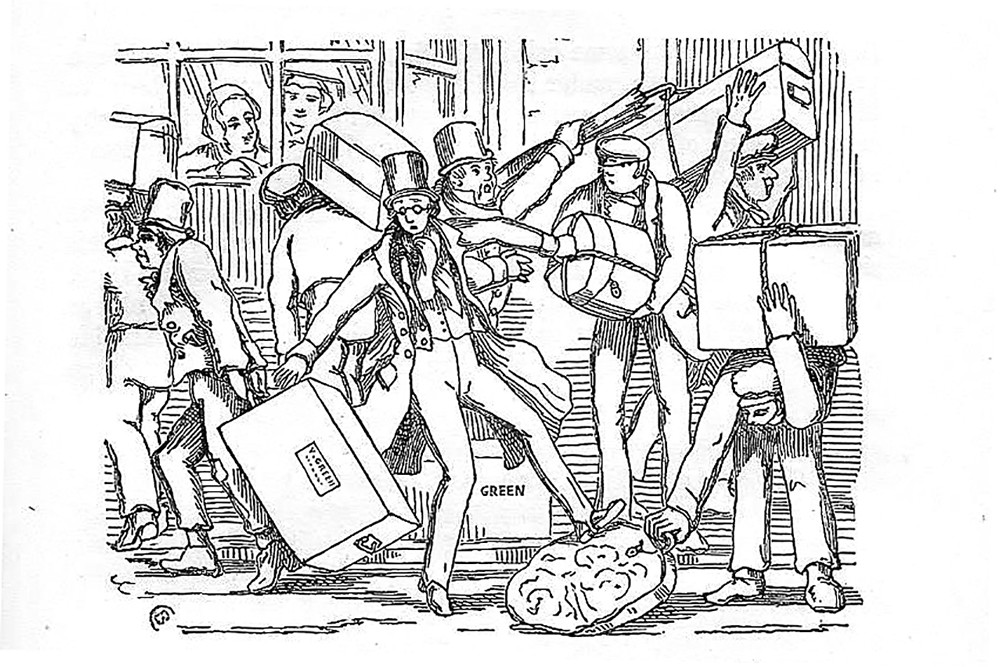

Left wanting more Victorian sparkiness, I wondered where next to turn. The Pickwick Papers is unique in its pace and optimism – G. K. Chesterton said it was ‘something nobler than a novel’, carrying ‘that sense of everlasting youth – a sense of the gods gone wandering in England’. Superb though Dickens’s later works are, there is in them that encroachment of increasing gloom and disenchantment that is almost entirely absent from Pickwick. So who, then? Trollope? Not really a thigh-slapper. Thackeray? Possibly. A dose of Becky Sharp or Pendennis might well do the trick. But then I have it: Cuthbert Bede. Well, the Reverend Edward Bradley writing as Cuthbert Bede. I first happened across him while mining the rewarding and delightfully chaotic depths of a West Country bookshop. He has been out of fashion for a considerable time, always a recommendation as far as I’m concerned, but I think his series beginning with The Adventures of Mr Verdant Green deserves to be regarded as a mid-Victorian comedy classic. In a space barely two feet wide between packed shelves, I managed to prise out a dusty 1855 sixth edition. I opened it and discovered a whole new pleasure. At the beginning of Chapter 1, ‘Cuthbert Bede MA’ suggests his readers consult ‘the unpublished volume of Burke’s Landed Gentry’ to learn a little about the Green family. There follows a long list of mishaps, including various forms of financial ruin and the death of a Green blown up in his laboratory ‘when just on the point of discovering the elixir of life’. We quickly deduce that despite having a documented lineage stretching back to 1096, the Greens never get beyond a certain point in wealth or station. Bede tells us:This sets everything up nicely for the introduction of Bede’s unlikely hero, young Mr Verdant Green, a rather weedy, bespectacled Oxford freshman. We know he’s weedy thanks to the wealth of illustrations, all drawn by the author and as amusing as the stories themselves. Initially, the poor lad is fussed over by his mother, three sisters – Miss Helen, Miss Fanny and Miss Mary – and a spinster aunt, Miss Virginia Verdant, as they prepare to send him off on his academic adventure. There is no little confusion, given that he is the first of the Greens to attend university. The family consults those in the know about such things, and these worthies include the considerably more worldly rector, Mr Larkyns (there always has to be a rector in this kind of Victorian tale), viewed as the fount of all knowledge because he attended university himself, and has an undergraduate son. Bede has great fun with this, especially when the subject of university practicalities first comes up during one of Mr Larkyns’s visits.we may perhaps ascribe these circumstances to the fact of finding the Greens, generation after generation, made the dupes of more astute minds, and when the hour of danger came, left to manage their own affairs in the best way they could – a way that commonly ended in their mismanagement and total confusion. Indeed, the idiosyncrasy of the family appears to have been so well known that we continually meet with them performing the character of catspaw to some monkey who had seen and understood much more of the world than they had – putting their hands to the fire, and only finding their mistake when they had burned their fingers.

The rector’s advice is also sought on the choice of college, and without hesitation he recommends the faintly familiar-sounding Brazen-face College, where a friend of his, Dr Portman, is the Master. Our hero is eventually torn from the bosom of his family by his father, and the pair endure a horrendously uncomfortable coach journey to Oxford in a carriage crammed with other students who are in annoyingly high spirits. Poor Verdant’s leg is immediately and mercilessly pulled – and so is his father’s. Once safely at Oxford, the Greens procure the services of a hopeless guide who knows even less about the city than they do; purchase ‘that elegant cap and preposterous gown which constitute the present academical dress of the Oxford undergraduate’ for Verdant; and lay claim to his rooms at Brazenface. Mr Green then departs and vulnerable Verdant is very much on his own. The gently amusing tales that follow give us an insight into the jokes, manners, speech and social life of a Victorian university with its contemporary slang. Verdant Green’s wire-rimmed spectacles result in his immediately being called ‘Gig-lamps’. The Oxford English Dictionary confirms that this 1853 usage is the word’s earliest recorded. The OED also credits Bede with the first use of ‘bags’ for ‘trousers’, and ‘shandygaff’, the forerunner of ‘shandy’. Tensions between Town and Gown come to the fore in The Further Adventures of Mr Verdant Green, in the build-up to the traditional Guy Fawkes Night brawl in the city’s streets. One of Green’s friends, Fosbrooke, decides to enlist the pugilistic help of the Putney Pet, a grizzled prizefighter:The motherly ears of Mrs Green had been caught by the word ‘matriculation’, a phrase quite unknown to her; and she said: ‘If it’s vaccination that you mean, Mr Larkyns, my dear Verdant was done only last year, when we thought the small-pox was about; so I think he’s quite safe.’

The friends accompany the Pet into the street and are soon in the thick of the action:There was no mistaking the profession of this gentleman . . . ‘Bruiser’ was plainly written in his personal appearance, from his hard-featured, low-browed, battered, hang-dog face, to his thickset frame, and the powerful muscular development of the upper part of his person . . . The Pet was attired in a dark olive-green cutaway coat, buttoned over a waistcoat of a violent-coloured plaid, a pair of white cord trousers that fitted tightly to the leg, and a white-spotted blue handkerchief, which was twisted round a neck that might have served as a model for the Minotaur’s.

And on it goes until the Pet is triumphant and the townsmen routed – all brilliantly and hilariously illustrated in picture and word by the author. In the meantime, of course, Verdant gets well and truly drubbed. We see him homesick, drunk, humiliated, financially embarrassed. He is the perennial victim, the butt of every prank, but over time he grows in stature, accumulates a gang of fiercely loyal friends and completes the awkward transition from cosseted mummy’s boy to man. Edward Bradley, alias Cuthbert Bede, had a talent for thinking in pictures, and as a child displayed an early flair for drawing. The second son of a surgeon, Thomas Bradley, he was born in Swan Street, Kidderminster, on 25 March 1827. His brother Thomas also achieved some success as the author of two novels, published in 1874 and 1875, under the pseudonym Shelsley Beauchamp. Edward’s comfortable middle-class beginnings ensured that a good education followed. He went to Kidderminster Grammar School, and then to University College, Durham, graduating in 1848. This was doubtless the inspiration for his nom de plume, Durham being the resting-place of both St Cuthbert – whose body was brought to the city by monks from Lindisfarne – and the Venerable Bede. Bradley had developed an increasing interest in religion and soon decided he wanted to play an active part himself, taking his licentiate of theology in 1849. At 21, he was still too young to be accepted for ordination by the Church of England, and so he killed time by spending a year studying at Oxford. His experiences there were to become the foundation of the Verdant Green books. While up, he also forged what would become a lifelong friend-ship with a fellow student, John George Wood. The two had a lot in common – both were the sons of surgeons and both wished to go into the Church. London-born Wood went on to become a famous parson naturalist, whose weighty tomes on natural history can still be found in second-hand bookshops across the country. Wood is thought to be Bradley’s model for Verdant Green’s extrovert best friend, Mister Bouncer. The wait in Oxford came to an end, and Edward Bradley began his Church of England career as curate of Glatton-with-Holme in Huntingdonshire, where he remained for four years. He had had his first work published by Bentley’s Miscellany in 1846, but by the time he arrived in Glatton his output had gathered momentum, with drawings and articles appearing regularly in the Illustrated London News. Journalism was one thing. Becoming a full-blown author was another, and Bradley encountered great difficulties when he began touting The Adventures of Mr Verdant Green around the publishers. For this reason, the three parts of the story were first published separately: The Adventures of Mr Verdant Green, an Oxford Freshman (1853), The Further Adventures of Mr Verdant Green, an Oxford Undergraduate (1854) and Mr Verdant Green Married and Done For (1857). Such was their popularity they were subsequently issued to great acclaim in one volume – the combined title had sold 100,000 copies by 1870, but Bradley received just £350 for his efforts. A much later sequel to the series, Little Mister Bouncer and His Friend Verdant Green, appeared in 1893 and was also a moderate success. During these busy literary years, Bradley held clerical positions in Worcestershire, Staffordshire, Huntingdonshire again, and Rutland. His last post was as vicar of Lenton in Lincolnshire, where he established a free library, a school bank, winter entertainments and various improvement societies. Bradley married Harriet Amelia Hancocks in December 1858, and the couple had two sons – Cuthbert, himself a talented animal artist who also had caricatures published in Vanity Fair, and Henry, who would follow his father into the clergy. Bradley knew many leading literary figures, including Dickens’s illustrator George Cruikshank, who taught him wood engraving, and the novelist Albert Smith, whose brother Arthur arranged Dickens’s readings in 1858 and 1861. Bradley died at the vicarage in Lenton on 12 December 1889, aged 62. He is buried at Stretton, in Rutland. The day after his death The Times published a slightly sniffy obituary.[The Pet] had agreeable remarks for each of his opponents . . . to one gentleman he would pleasantly observe as he tapped him on the chest: ‘Bellows to mend for you, my buck!’ or else: ‘There’s a regular rib-roaster for you!’ or else, in the still more elegant imagery of the Ring: ‘There’s a squelcher in the bread-basket that’ll stop your dancing, my kivey!’

The obituarist, however, concedes:It is impossible to say by what means Mr Bradley managed to draw a picture of Oxford life – not a very high order of life, it is true – whether it was from personal visits or from conversation with friends whose crude stories were transformed by something like genius into the Oxford career of an undergraduate . . .

Well, for me, the billiards, tobacco and wine are essential to these stories of mid-nineteenth-century undergraduate life. Bradley may not be a writer of depth, but he works brilliantly in the shallows.It is sufficient to say that not only did the book cause unquenchable laughter among outsiders, but Oxford men are even now ready to say that it was a faithful picture of one side of University life as they knew it. The fun of the book was of the purest and most innocent kind, though possibly billiards, tobacco and wine held too prominent a place.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 55 © Anthony Longden 2017

About the contributor

Anthony Longden is a journalist, media consultant and former newspaper editor. The experiences of Verdant Green put him right off the idea of going to university.