“Dear Michael, Guess how much I love you”: A father’s enchanting daily letters and drawings to his son are a powerful and tender portrait of paternal love — and of Britain emerging from war’s shadow

A new book collates letters and drawings to give insight into life in the 1940s

Charles Phillipson took up the pen after being diagnosed with multiple sclerosis

Artist born in Manchester, would write and draw for his son Michael every day

They were the worst of times when Charles Phillipson, a company publicist and amateur artist, took up his pen to create a gift for his small son, Michael.

Charles had already been diagnosed with progressive multiple sclerosis and Britain was at war with Germany. But neither fact could stem the extraordinary energy of a father’s love and the creative skill with which he expressed it.

A first little book of the alphabet was followed by this series of precious letters, dated from 1945 to 1947. The letters, writes Michael Phillipson in his introduction to this beautiful volume, “affirmed his love for me and revealed his way of engaging with my world”.

What was that world? A shared Anderson shelter in the garden, air raid sirens, Daddy striding across a field path to the local station to catch the train to Burnage in Manchester’s suburbs, men in long overcoats and trilby hats, Mummy and Daddy going to hear a Halle orchestral concert.

All that, and the quirkiness of the everyday, was recorded by a father writing a daily letter to his son, illustrated by a speedy pen-and-ink drawing. They combine to make an enchanting evocation of a lost world.

Charles Phillipson was born in Manchester in 1904 and from the age of 12 was sent to evening classes three nights a week to foster his artistic gifts. Some of the classes were also attended by L. S. Lowry, who surely never drew with the free-wheeling talent and brilliant economy of line shown by Charles.

Children usually left school at 14 in those days, and Charles was no exception. Nowadays, such a boy would loaf about moodily being ‘an artist’, but then it was necessary to buckle down and learn commercial printing and lettering techniques.

Art for art’s sake could only be a hobby for a man who had to earn a living to support (later) a wife and one child.

Charles’s letters were written on sheets torn from a pad of office scrap paper, with Michael’s full name on one side, plus a drawn ‘stamp’ — different each day and often showing a duck or other creature wearing a crown, like the King’s. The sheets were folded like a real letter.

In lunch or coffee breaks, Charles would dash off the diary-like notes, turning some of them into casual little lessons by underlining ‘silent’ letters and breaking up two-syllable words to help reading. His wife, Marjorie, recognised their uniqueness and saved every one.

What a gift to us that she did — for this set of letters and drawings give a rare insight into suburban life in the 1940s.

On February 22, 1945, Charles writes: ‘When you see all the heavy things a soldier has to carry, you wonder how he can do it. Today I saw many of them waiting for the train with kit bags piled up on the platform.’

And there they all are in the drawing. On March 22, 1945, we meet . . . the lady porter at Burnage station.

‘During war time lots of ladies have to do the work that men do in peacetime. Love from Daddy.’

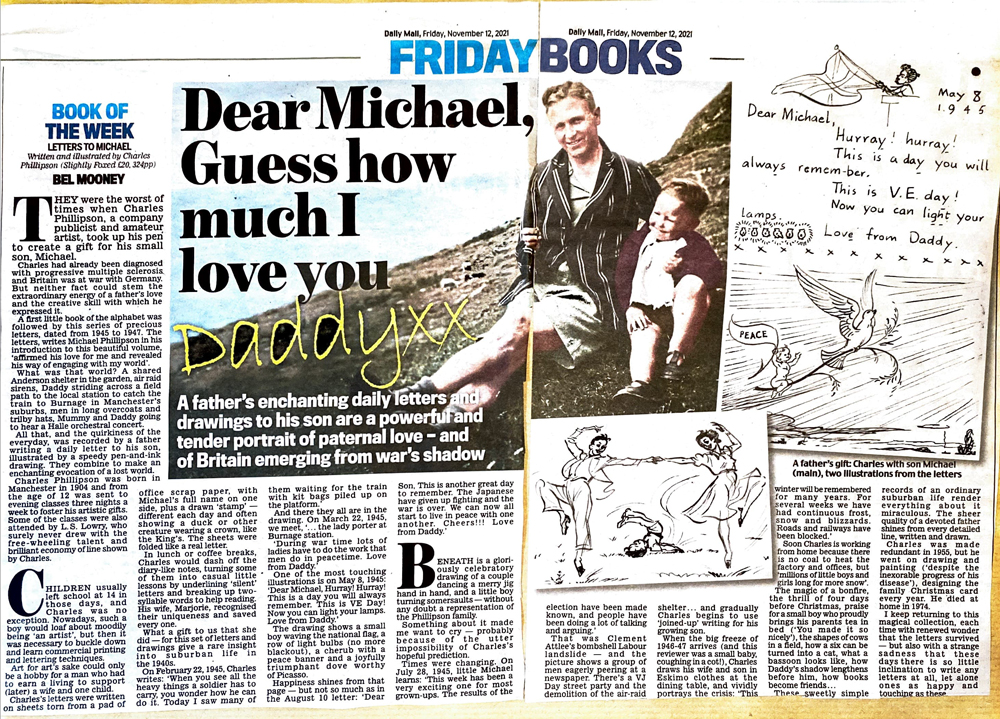

One of the most touching illustrations is on May 8, 1945: ‘Dear Michael, Hurray! Hurray! This is a day you will always remember. This is VE Day! Now you can light your lamps. Love from Daddy.’

The drawing shows a small boy waving the national flag, a row of light bulbs (no more blackout), a cherub with a peace banner and a joyfully triumphant dove worthy of Picasso.

Happiness shines from that page — but not so much as in the August 10 letter: ‘Dear Son, This is another great day to remember. The Japanese have given up fighting and the war is over. We can now all start to live in peace with one another. Cheers!!! Love from Daddy.’

Beneath is a gloriously celebratory drawing of a couple dancing a merry jig hand in hand, and a little boy turning somersaults — without any doubt a representation of the Phillipson family.

Something about it made me want to cry — probably because of the utter impossibility of Charles’s hopeful prediction.

Times were changing. On July 28, 1945, little Michael learns: ‘This week has been a very exciting one for most grown-ups. The results of the election have been made known, and people have been doing a lot of talking and arguing.’

That was Clement Attlee’s bombshell Labour landslide — and the picture shows a group of men eagerly peering at a newspaper. There’s a VJ Day street party and the demolition of the air-raid shelter . . . and gradually Charles begins to use ‘joined-up’ writing for his growing son.

When the big freeze of 1946-47 arrives (and this reviewer was a small baby, coughing in a cot!), Charles draws his wife and son in Eskimo clothes at the dining table, and vividly portrays the crisis: ‘This winter will be remembered for many years. For several weeks we have had continuous frost, snow and blizzards. Roads and railways have been blocked.’

Soon Charles is working from home because there is no coal to heat the factory and offices, but ‘millions of little boys and girls long for more snow’.

The magic of a bonfire, the thrill of four days before Christmas, praise for a small boy who proudly brings his parents tea in bed (‘You made it so nicely’), the shapes of cows in a field, how a six can be turned into a cat, what a bassoon looks like, how Daddy’s shadow lengthens before him, how books become friends . . .

These sweetly simple records of an ordinary suburban life render everything about it miraculous. The sheer quality of a devoted father shines from every detailed line, written and drawn.

Charles was made redundant in 1955, but he went on drawing and painting (‘despite the inexorable progress of his disease’), designing the family Christmas card every year. He died at home in 1974.

I keep returning to this magical collection, each time with renewed wonder that the letters survived — but also with a strange sadness that these days there is so little inclination to write any letters at all, let alone ones as happy and touching as these.