Every child who enjoys reading will sooner or later begin to explore the world of grown-up books. The first ones I ever read were bought in an antique shop in the picturesque town of Cromarty on the Black Isle. I can’t recall my exact age or the year – about thirteen, around 1975 – but the second-hand paperbacks I found there and devoured over that three-week family holiday are very clear in my mind.

My literary hoard included a biography of Kit Carson, a POW escape story, an Arthur Hailey novel and Walter Lord’s A Night to Remember. Of these, the only one I’ve returned to down the years is Lord’s haunting minute-by-minute account of the sinking of the Titanic. Many books about this famous and ill-fated ship have come and gone, but A Night to Remember has outlived them all. First published in 1955, it remains in print today and is as fresh and compelling as ever.

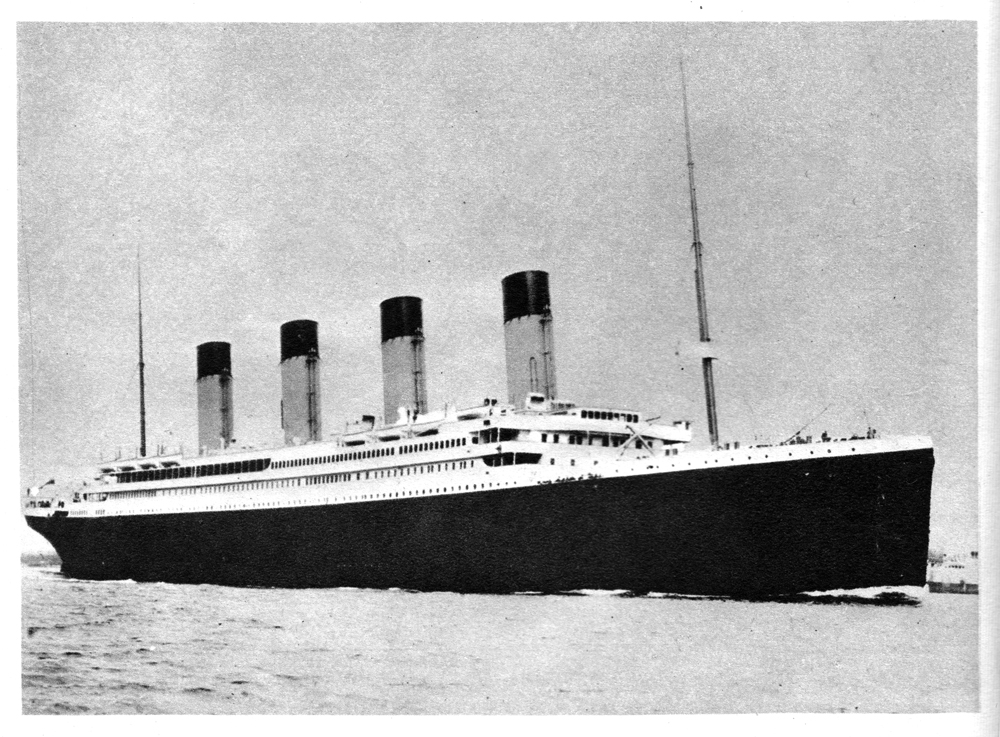

The loss of the Titanic has loomed large in the popular imagination from the very beginning – thousands of people lined the quays to watch the Carpathia arrive in New York with the survivors. The Titanic was, after all, the most luxurious ship that had ever taken to the waves, boasted a passenger list which included the rich and the famous, and was popularly regarded as unsinkable – all this we know. But dull books can be written about fascinating subjects.

So why is Walter Lord’s account so gripping? Put very simply, he takes us there, and he makes us care. A Night to Remember has no routine opening chapters about the history of the White Star Line or how the ship was built. Instead, from the very start, we are there in the North Atlantic on that freezing night in 1912, high up in the crow’s-nest with Frederick Fleet as he keeps lookout and suddenly sees the iceberg straight ahead. In the pages that f

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inEvery child who enjoys reading will sooner or later begin to explore the world of grown-up books. The first ones I ever read were bought in an antique shop in the picturesque town of Cromarty on the Black Isle. I can’t recall my exact age or the year – about thirteen, around 1975 – but the second-hand paperbacks I found there and devoured over that three-week family holiday are very clear in my mind.

My literary hoard included a biography of Kit Carson, a POW escape story, an Arthur Hailey novel and Walter Lord’s A Night to Remember. Of these, the only one I’ve returned to down the years is Lord’s haunting minute-by-minute account of the sinking of the Titanic. Many books about this famous and ill-fated ship have come and gone, but A Night to Remember has outlived them all. First published in 1955, it remains in print today and is as fresh and compelling as ever. The loss of the Titanic has loomed large in the popular imagination from the very beginning – thousands of people lined the quays to watch the Carpathia arrive in New York with the survivors. The Titanic was, after all, the most luxurious ship that had ever taken to the waves, boasted a passenger list which included the rich and the famous, and was popularly regarded as unsinkable – all this we know. But dull books can be written about fascinating subjects. So why is Walter Lord’s account so gripping? Put very simply, he takes us there, and he makes us care. A Night to Remember has no routine opening chapters about the history of the White Star Line or how the ship was built. Instead, from the very start, we are there in the North Atlantic on that freezing night in 1912, high up in the crow’s-nest with Frederick Fleet as he keeps lookout and suddenly sees the iceberg straight ahead. In the pages that follow we’re introduced to many other characters and discover what they saw, felt and said as events unfolded over the next terrible few hours. Lord based his narrative on interviews he had conducted with survivors of the disaster, and this gives it a directness and authenticity that no formal history could hope to match. The Titanic has often been considered a microcosm of Edwardian society – the rich enjoying their leisure in spacious upper staterooms, the poor cramped down below in third-class or labouring in the bowels of the ship, shovelling coal to keep the great engines turning. Lord allows us to meet them all: millionaires, stokers, stewards, ship’s officers, husbands and wives, youngsters seeking a new life in America. A Night to Remember is the story of people caught up in extraordinary circumstances. Living in a world of terrorist atrocities and extreme weather events, it’s easy for us to empathise with them as they face an unexpected and growing peril. Lord reveals how haphazard and chaotic the evacuation of passengers into the lifeboats really was. The rule of course was ‘women and children first’ but many wives did not want to leave their husbands, did not realize how dangerous the position was, or felt safer on the ‘unsinkable ship’ than adrift in a tiny open boat on the vast, cold Atlantic. The story of who got into a lifeboat, the difference between living and dying, is central to the drama. Lord gives us many moving vignettes to illustrate this, including the self-sacrifice of some male passengers as they escorted their wives or other women to the boats: ‘Mr Turrell Cavendish said nothing to Mrs Cavendish. Just a kiss . . . a long look . . . another kiss . . . and he disappeared into the crowd.’ Mrs Walter D. Douglas begs her husband to come with her. ‘“No,” Mr Douglas replied turning away, “I must be a gentleman.”’ Such sentiments are echoed by Benjamin Guggenheim who, along with his manservant, puts on his best clothes to go down with the ship in style. These codes of courage and honour would soon have to rise to a more prolonged challenge in the face of the coming war’s machine guns, flame-throwers and gas clouds. The failure of modern technology as personified by the Titanic was a prelude to its being harnessed in the cause of mass slaughter. The sinking of the Titanic cast a cloud over the fabled long Edwardian summer. The old certainties were beginning to fail. Courage was not of course confined to the men. On rereading the book recently, I was struck by the story of Edith Evans who allowed another woman to climb into a boat first as she had children waiting for her at home. This caused Edith to miss her own chance as the boat was quickly lowered away. It was the last one. Anxiously looking up the passenger list provided at the end of the book, in which the survivors’ names are printed in italics, my worst fears were confirmed. Miss Evans’s thoughtfulness proved fatal. Who got into a lifeboat could be frighteningly arbitrary. On the starboard side of the ship the First Officer, Murdoch, allowed men to climb in if there was room and no women were waiting; while on the other side, the Second Officer, Lightroller, played by Kenneth More in the 1958 film version, controversially forbade male passengers, including boys, any chance of escape even when the boats were half empty. Lord follows the fortunes of some men who saved themselves by jumping into boats as they were lowered, or by swimming over to them once afloat. Few who took to the ocean could survive long in such icy waters. Initiative and presence of mind saved a steerage passenger, Anna Sjoblom. Stuck down below, she managed to reach the boat deck by climbing an emergency ladder reserved for the crew. Despite the fact that official enquiries were held on both sides of the Atlantic, an astonishing number of myths, legends and mysteries have grown up about the Titanic over the years, with virtually every aspect of the story being open to several interpretations. Even something as simple as whether the lookouts were supposed to have, or use, binoculars is hotly debated. Whole books have also been written on the question of the Californian, the ship that lay ten miles away apparently oblivious to the Titanic’s plight. And the actions and motivations of key figures such as Bruce Ismay, the White Star Line’s Managing Director, have been put under the microscope. Lord closes his account by noting that only a rash man would set himself up as final arbiter of all that happened. There are some aspects of the story which he doesn’t tackle, such as the likely suicide of First Officer Murdoch – the man unlucky enough to have been in charge of the ship when the collision occurred. Nevertheless, for clarity and sheer readability, it is A Night to Remember which will continue to be the version of events that brings the sinking vividly alive and helps to immortalize all who were there.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 67 © David Fleming 2020

About the contributor

David Fleming used to be a Customs Officer and is now a freelance writer. He lives in Broughty Ferry and enjoys looking out to sea.