Aspiring young writers of fiction wish to be stylish. For many of them style is more essential than content, perhaps more important than sincerity. They want their prose to be inimitable, like Conrad’s or Hemingway’s, so that readers might identify their authorship from a single paragraph. As a young man, I was certainly like that, even though fiction didn’t turn out to be my thing. And of course I preferred to read novels by writers who themselves had a pronounced style.

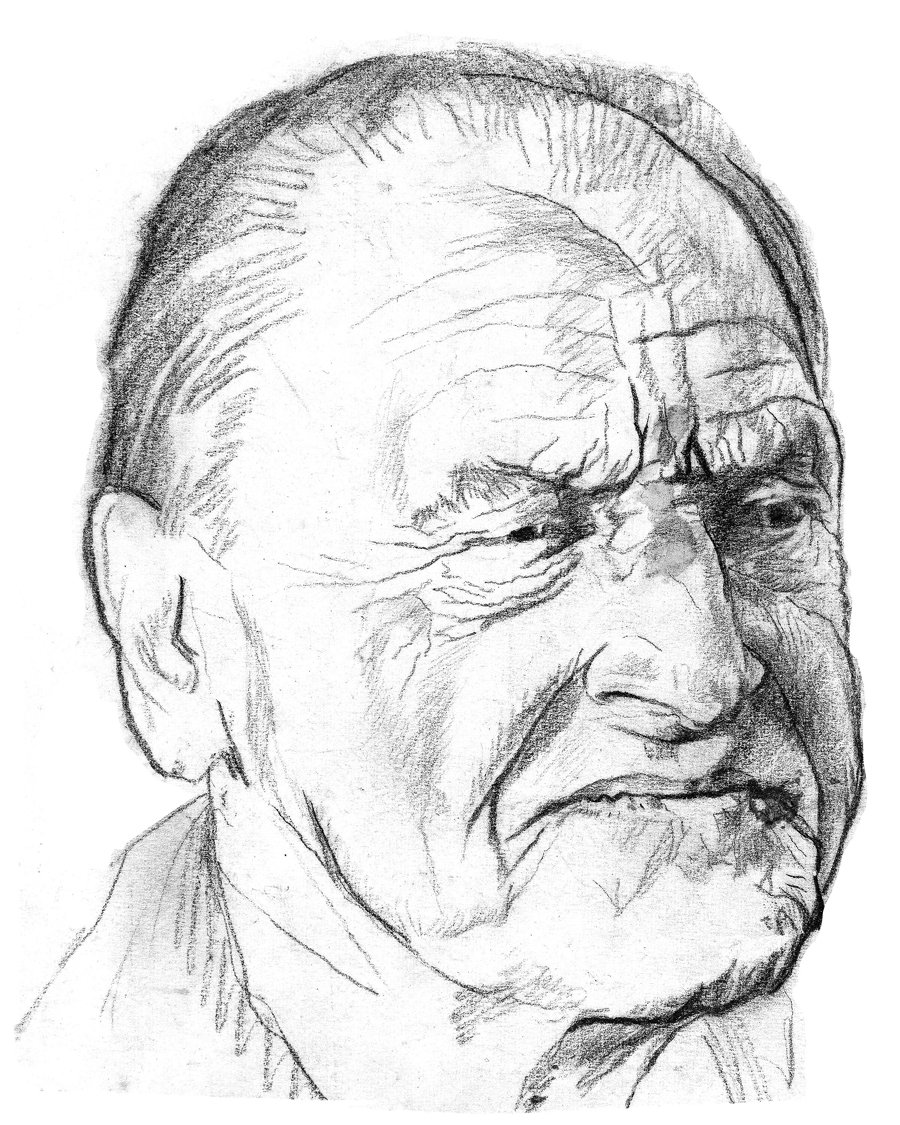

More than forty years ago, when reading Orwell’s collected essays, I came across an autobiographical note that the author had written in 1940. After listing his favourite modern writers – Joyce, Eliot and D. H. Lawrence – he declared that the one who had influenced him most was Somerset Maugham, whom he admired immensely ‘for his power of telling a story straightforwardly and without frills’. Despite my respect for Orwell’s judgement, I was suspicious of that phrase about ‘frills’ – it suggested he was dismissing style – but I dutifully read some of Maugham’s novels and stories.

What disillusionment I felt! How could Orwell have admired a writer who described people in such banal language, how one man was ‘large and stoutish’ while another was big ‘but fat, with grey hair’; or a woman who was ‘shortish and stout’ and another who was ‘tallish . . . with a good deal of pale brown hair’? How did an author help convey a scene in the Tropics with the phrase ‘the sun beat fiercely’ or tell us much about China with the clichéd and portentous statement, ‘Here was the East, immemorial, dark and inscrutable.’ When I later read Maugham’s own assessment that he had ‘no lyrical quality’, ‘little gift of metaphor’ and ‘small power of imagination’, I felt that at least he possessed some self-awareness.

Some decades later I st

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inAspiring young writers of fiction wish to be stylish. For many of them style is more essential than content, perhaps more important than sincerity. They want their prose to be inimitable, like Conrad’s or Hemingway’s, so that readers might identify their authorship from a single paragraph. As a young man, I was certainly like that, even though fiction didn’t turn out to be my thing. And of course I preferred to read novels by writers who themselves had a pronounced style.

More than forty years ago, when reading Orwell’s collected essays, I came across an autobiographical note that the author had written in 1940. After listing his favourite modern writers – Joyce, Eliot and D. H. Lawrence – he declared that the one who had influenced him most was Somerset Maugham, whom he admired immensely ‘for his power of telling a story straightforwardly and without frills’. Despite my respect for Orwell’s judgement, I was suspicious of that phrase about ‘frills’ – it suggested he was dismissing style – but I dutifully read some of Maugham’s novels and stories. What disillusionment I felt! How could Orwell have admired a writer who described people in such banal language, how one man was ‘large and stoutish’ while another was big ‘but fat, with grey hair’; or a woman who was ‘shortish and stout’ and another who was ‘tallish . . . with a good deal of pale brown hair’? How did an author help convey a scene in the Tropics with the phrase ‘the sun beat fiercely’ or tell us much about China with the clichéd and portentous statement, ‘Here was the East, immemorial, dark and inscrutable.’ When I later read Maugham’s own assessment that he had ‘no lyrical quality’, ‘little gift of metaphor’ and ‘small power of imagination’, I felt that at least he possessed some self-awareness. Some decades later I stayed a few days in Singapore. I was travelling from Perth, Scotland to Perth, Australia (rather a long way to go to watch England lose a Test Match) and thought I should acknowledge the fact that Asia lay in between by stopping off somewhere. Like many of us, I enjoy reading writers in appropriate places – Ruskin in Venice, Proust in Normandy – so I tried Maugham again. Of course nowadays Singapore is no more redolent of Maugham than it is of Raffles; looking for footsteps there is as futile as trying to listen to a nightingale on Hampstead Heath. Yet this time I did appreciate the fourth point of Maugham’s self-assessment: that he possessed ‘an acute power of observation’ and that he was able to see ‘a great many things that other people missed’. His characters might be banal and be described banally, but they were at least real and living in real situations. I recognized that Maugham possessed extraordinary psychological insight. Last winter in India I reread the Far East fiction, the short stories and two novels, The Painted Veil and The Narrow Corner. (I did not go back to The Moon and Sixpence, which is partly set in Polynesia – too far east – and libels Gauguin’s character, unappealing though it may have been.) I had several days to spare between the Arts Festival in Goa and The Times of India Litfest in Mumbai, and I spent them beside a bay in western India. Luckily there were no tourists there because some years ago an environmental disaster (some blamed the tsunami, others the grounding of a vast tanker) had caused nearly all the sand to disappear. Each afternoon I read Maugham under a rough canopy on the beach, watching fishermen bringing in the catch, listening to the sounds of women shouting to each other in Konkani, their voices competing with the screeching of parrots and the cawing of crows. The bay was congested with fishing boats, blue hulls under green awnings, lying low in the water. In the evening a black bullock with painted yellow horns was led along the beach, and I watched the sun going down beyond the headland, silhouetting the palm trees against the sky. As I sat enjoying the books, I felt that it was a setting Maugham would have appreciated, and I wondered why he had never written a story set in India. Later I discovered it was because, ‘so far as [Indian] stories were concerned’, he believed that ‘Kipling had written all the good ones’ – an absurd belief, as Maugham himself came to realize. Kipling had lived in a couple of cities in northern India and had returned to England at the age of 23. He had left plenty of scope and space for a rival storyteller. Maugham’s travels in eastern Asia took in Burma, Siam, China and Cambodia, but the best of his stories are located in and around the Federated Malay States. He actually visited the Far East only twice, in 1921 and 1925, spending a total of ten months there, a far shorter period than Orwell’s five years as a policeman in Burma or Kipling’s six and a half years as a journalist in India.* This accounts for certain limitations in his work. Unlike Orwell he made no attempt to write about imperialism and its effects on the people under colonial rule. And unlike Kipling he made little effort to make real characters of his ‘natives’: there is no Lama or Babu or dowager Sahiba as in Kim, but a few rather stock characters: the houseboy, the discarded mistress, the wily Chinese clerk in Singapore. Yet as a portrait of the British in the Far East at the time, the stories are extraordinarily perceptive. They contain a surprising amount of tension and passion; there are an unusual number of murders as a result; and there is enough adultery to rival Kipling’s Under the Deodars and Plain Tales from the Hills. Yet behind the excitements Maugham’s descriptions of the realities of colonial life are concise and well-observed. And as I read them under the awning on my sandless beach, I recognized that they exhibited the three virtues he regarded as essential: lucidity, simplicity and euphony. In her wonderful biography The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham, Selina Hastings ascribed the success of The Painted Veil (which is set in China) to the author’s ‘two greatest strengths, his dramatist’s infallible ear for dialogue and his instinct for psychological truth’. The Malayan tales contain additional strengths such as a vivid sense of place and an understanding of the lives of the British expatriates, the planters and the district officers, the routines of social life, the drive to the club, the evening cocktail and the bridge table afterwards. Maugham was well attuned to the nuances of social class, and he could sense both the superior attitudes of officials and the resentments of the men who ran the rubber plantations. And he observed the monotony of expatriate life and its loneliness, not just the boredom of wives with nothing to do but boss the servants, but also their vulnerability, their sense of alienness, their reliance on routine to keep themselves from losing control and ‘going to seed’. Maugham is both compassionate and empathetic to such people. In ‘The Outstation’ he does not mock the rather absurd figure of Mr Warburton, a senior official who dresses as if for a club in Pall Mall even when he is dining alone in the jungle. And he is sympathetic to lonely wives even when they are adulterous. His bisexuality (a good deal more inclined towards men than to women) may have wrecked his marriage, but it helped provide him with a sensibility seldom rivalled among male novelists in his handling of female behaviour and motivation. He was thus able to inhabit his women characters as Alberto Moravia did in his remarkable novel about an Italian prostitute, La romana. Kitty Fane in The Painted Veil, torn between a despised husband and a caddish lover (with an appalling mother in the background), is one of the great female figures of fiction. Somerset Maugham’s ‘research’ technique was simple: he travelled, he observed and he listened. His travelling companion or ‘secretary’, Gerald Haxton, got drunk and behaved badly but he did meet people in bars who told him good stories which he repeated to his employer. And Maugham himself was capable of acquiring ‘copy’ simply by asking the right questions. In his story ‘Masterson’ he described how a man ‘in some lonely post in the jungle’ would give him a drink and then – after a few more drinks – say ‘Would it bore you awfully if I told you about’ such-and-such an incident? In his memoir The Summing Up he recorded how, when ‘sitting over a siphon or two and a bottle of whisky . . . [within] the radius of an acetylene lamp . . . a man has told me stories about himself that I was sure he had never told to a living soul’. His temporary confidants may have enjoyed Maugham’s companionship for an evening, but they were not so appreciative when they read their stories, only mildly disguised, some years later in magazines and books. As one civil servant observed, Maugham’s passage through the Federated Malay States was ‘clearly marked by a trail of angry people’ who accused him of betraying their confidences and writing about only ‘the worst and least representative aspects of European life’ there: ‘murder, cowardice, drink, seduction, adultery’. Similar accusations (minus the murders) were made of Kipling’s tales of Simla. Yet there was a difference. The characters and events of Kipling’s stories were very seldom recognizable; Maugham’s often were. When drunk in a bar, Haxton learned about the murderous couple who became the Cartwrights in ‘Footsteps in the Jungle’. Staying in Kuala Lumpur, Maugham heard from her lawyer about Ethel Proudlock, a woman who in 1911 had murdered her lover after she discovered he had a Chinese mistress. The crime of Mrs Proudlock (transformed into Mrs Crosbie) was retold in the story ‘The Letter’ and publicized in Hearst’s International in 1924, in Maugham’s collection The Casuarina Tree in 1926, in the theatre (the murderess played by Gladys Cooper) in 1927 and in a Warner Brothers film (the role played by Bette Davis) in 1940. Perhaps we may sympathize with both sides, the artist who immortalized a British society living a brief, exotic existence in a part of the globe as far from Britain as it is possible to be, and a group of vulnerable men and women that had welcomed a visitor who, after enjoying their hospitality, broadcast their defects in three different art forms. Whatever the wrongs of the matter, it says something for Maugham’s talent that, however banally Mrs Crosbie is described physically – ‘graceful’ and ‘unassuming’ with ‘a great deal of light brown hair’ – she was a character sufficiently interesting to be played by two great actresses. * Both Orwell and Kipling were born in India, the first in Bengal, where he remained for a year, the second in Bombay, where he stayed until he was 5.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 65 © David Gilmour 2020

About the contributor

David Gilmour is the author of Curzon, The Long Recessional: The Imperial Life of Rudyard Kipling and The British in India, all of which were reissued in paperback by Penguin last year.