Radio stations in my youth were always running phone-ins to find the greatest pop songs of all time – that is, of the last few decades. The top song, as I recall, was always the same: ‘Stairway to Heaven’. Likewise, polls of the greatest novels have their inevitable winners. Ask the public, and it’s The Lord of the Rings. Ask writers or critics, and it’s Ulysses or Proust. In 1998, Modern Library offered its 100 best English-language novels of the twentieth century. The list, determined by the editorial board, of course made Joyce No. 1. For me, one cheering inclusion was the book that scraped in at No. 100: The Magnificent Ambersons by Booth Tarkington. I had thought this splendid novel almost entirely forgotten, other than as source material for the brilliant but troubled 1942 Orson Welles film of the same name.

Booth Tarkington (1869–1946), a native of Indianapolis, was a prolific and highly popular writer from the appearance of his first novel, The Gentleman from Indiana, in 1899 to his death almost fifty years later. Twice winner of the Pulitzer Prize – for The Magnificent Ambersons (1918) and Alice Adams (1921) – he wrote or co-wrote over 20 plays, some of them major Broadway hits, in addition to 39 volumes of fiction, and each of his novels first appeared in magazines such as Harper’s and the Saturday Evening Post.

For the journalist Mark Sullivan, in his classic survey of early twentieth-century America, Our Times, Indiana was the typical American state, and Tarkington its typical voice: an unofficial laureate. This was a mixed blessing. Like many a writer in tune with his times, Tarkington fell from grace after his death. Today, along with Bulwer-Lytton, Hugh Walpole and John P. Marquand, he survives only in the shadowlands of yesterday’s bestsellers. Yet Tarkington at his best is more than merely the mouthpiece of his age. He not only

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inRadio stations in my youth were always running phone-ins to find the greatest pop songs of all time – that is, of the last few decades. The top song, as I recall, was always the same: ‘Stairway to Heaven’. Likewise, polls of the greatest novels have their inevitable winners. Ask the public, and it’s The Lord of the Rings. Ask writers or critics, and it’s Ulysses or Proust. In 1998, Modern Library offered its 100 best English-language novels of the twentieth century. The list, determined by the editorial board, of course made Joyce No. 1. For me, one cheering inclusion was the book that scraped in at No. 100: The Magnificent Ambersons by Booth Tarkington. I had thought this splendid novel almost entirely forgotten, other than as source material for the brilliant but troubled 1942 Orson Welles film of the same name.

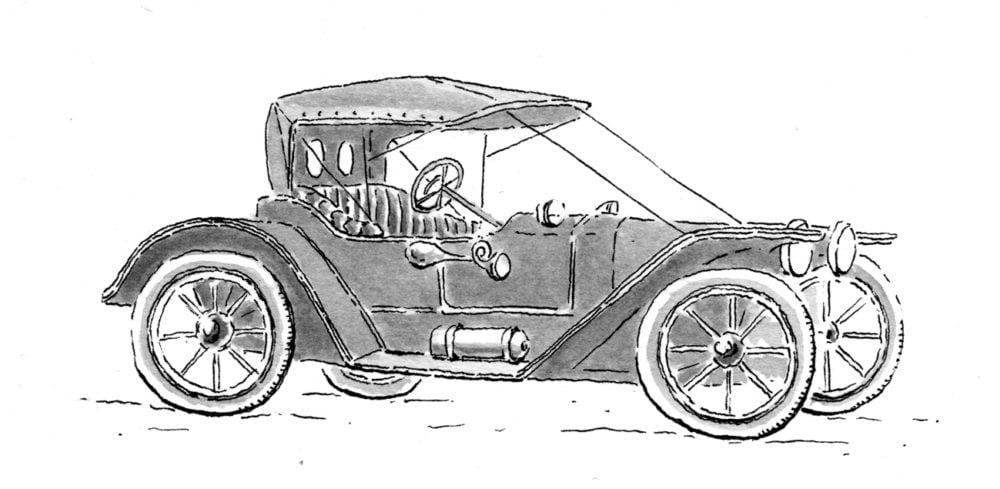

Booth Tarkington (1869–1946), a native of Indianapolis, was a prolific and highly popular writer from the appearance of his first novel, The Gentleman from Indiana, in 1899 to his death almost fifty years later. Twice winner of the Pulitzer Prize – for The Magnificent Ambersons (1918) and Alice Adams (1921) – he wrote or co-wrote over 20 plays, some of them major Broadway hits, in addition to 39 volumes of fiction, and each of his novels first appeared in magazines such as Harper’s and the Saturday Evening Post. For the journalist Mark Sullivan, in his classic survey of early twentieth-century America, Our Times, Indiana was the typical American state, and Tarkington its typical voice: an unofficial laureate. This was a mixed blessing. Like many a writer in tune with his times, Tarkington fell from grace after his death. Today, along with Bulwer-Lytton, Hugh Walpole and John P. Marquand, he survives only in the shadowlands of yesterday’s bestsellers. Yet Tarkington at his best is more than merely the mouthpiece of his age. He not only depicts his world but also analyses it with sadness, anger and irony. The Magnificent Ambersons is the second of three realistic novels of Midwestern life to which Tarkington gave the collective title ‘Growth’: the others are The Turmoil (1914) and The Midlander (1924). The ‘growth’ in question is what we would now call ‘economic growth’, that shibboleth of the modern age which, as all but economists and politicians know, is frequently as much a curse as a blessing. Tarkington, whose life is ably chronicled by James Woodress in Booth Tarkington: Gentleman from Indiana (1955), was shocked upon returning after years abroad to find the relaxed, leafy, genteel Indianapolis of his early life convulsed by industrialization and a rapid increase in population. The story he tells is, in effect, the story of the American Midwest and its rapid and ultimately catastrophic plunge into modernity. If The Magnificent Ambersons remains a compelling novel, it is because Tarkington conveys so powerfully what ‘progress’ means: aesthetically, ecologically, spiritually. Not the least of his merits is the detail with which he evokes his world: the opening sequence of The Magnificent Ambersons, echoed cleverly in the Welles film, is impressive in this regard. Spanning the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the story takes as its anti-hero George Amberson Minafer, son and heir of a wealthy family in a city which, though never named, is clearly Indianapolis. The Amberson mansion, centrepiece of a plush housing estate called Amberson Addition, is the finest place in town; in their ‘Midland city’, the Ambersons are aristocrats, even royalty. Spoiled by his vain mother Isabel, George takes entirely seriously the ‘magnificence’ of his heritage. If he behaves appallingly and expects to get away with it, this is because he knows that, as an Amberson, he can. Many look forward to the day when George will receive his comeuppance, though the great day seems fated never to come – but in the end it does, spectacularly. Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks, his great novel of German bourgeois life, bore the subtitle ‘The Decline of a Family’; in England, Galsworthy’s The Forsyte Saga, beginning with The Man of Property, chronicled a similar decay; The Magnificent Ambersons is an American take on the same theme. For the Ambersons, ‘magnificence’ swiftly fades; George Amberson Minafer’s tragedy is that he lives in a dream of the past. What ruins sedate, old-fashioned Indianapolis for Tarkington, and for the Ambersons, is the introduction of modern industry with its attendant noise, clutter and filth. Early twentieth-century Indianapolis vied with Detroit as the centre of America’s automobile industry. In Tarkington’s novel, two of the main characters are the car manufacturer Eugene Morgan, who loves George’s mother, and his daughter Lucy, with whom George becomes involved; a significant motif is the advent of cars and the effect this has upon every aspect of life in the ‘Midland city’. Naturally, aristocratic George Amberson Minafer hates cars from the first; as a boy, he taunts drivers of clumsy early cars with the cry, ‘Git a hoss! Git a hoss!’ In one of the novel’s most striking passages, George insults Lucy’s father, whose interest in his mother rouses him to a startling Oedipal envy, by telling him that automobiles ‘had no business to be invented’. Morgan, refusing to rise to the bait, says thoughtfully to the assembled company:I’m not sure he’s wrong about automobiles . . . With all their speed forward they may be a step backward in civilization – that is, in spiritual civilization. It may be that they will not add to the beauty of the world, nor to the life of men’s souls. I am not sure. But automobiles have come, and they bring a greater change in our life than most of us suspect. They are here, and almost all outward things are going to be different because of what they bring. They are going to alter war, and they are going to alter peace. I think men’s minds are going to be changed in subtle ways because of automobiles; just how, though, I could hardly guess. But you can’t have the immense outward changes that they will cause without some inward ones, and it may be that George is right, and that the spiritual alteration will be bad for us. Perhaps, ten or twenty years from now, if we can see the inward change in men by that time, I shouldn’t be able to defend the gasoline engine, but would have to agree with him that automobiles ‘had no business to be invented’.The Magnificent Ambersons mingles a powerful if morally ambiguous nostalgia with a throbbing sense of doom. Is it a great novel? Perhaps not. Tarkington lacks the brutal, crude power of his Indiana contemporary Theodore Dreiser, with whom he is often compared adversely; as a chronicler of Americana, he has neither the elegiac beauty of F. Scott Fitzgerald nor the exuberant satirical flair of Sinclair Lewis. Yet today, at the ragged end of a century of ‘economic growth’, Tarkington’s saga of bourgeois decline emerges as a prophetic work, exposing the emptiness of money-fuelled ‘greatness’ and a purely material progress which, racing forward like Eugene Morgan’s automobiles, leaves the human spirit trailing in the dust.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 41 © David Rain 2014

About the contributor

David Rain, an Australian novelist who lives in London, is the author of The Heat of the Sun and the forthcoming Volcano Street. He is slowly collecting the complete works of Booth Tarkington.