Recently, the lack of anything worth watching on TV sent me, once again, to the DVD of Visconti’s lush 1963 film of Giuseppe Lampedusa’s The Leopard (1958). If one loves a book, the idea that a film version might be in a different way as satisfactory as the original seems a sort of betrayal. But at the very least I find it impossible to reread the book without Burt Lancaster’s Prince Fabrizio, Claudia Cardinale’s ravishing Angelica and Alain Delon’s handsome, selfregarding Tancredi illustrating the narrative as a most remarkable set of lithographs might.

The author of course provided his own vivid panorama before the film came along, and a reader with no previous sense of the barren, dusty landscape of Sicily and no knowledge of or special interest in the turmoil of Italian society during the Risorgimento does not have to read long before being immersed in the place and time of the novel, and understanding the creaking uncertainty and shock experienced by the society of which Prince Fabrizio is the head.

We meet him and his family first at morning prayers in the vast family palace outside Palermo. Rising from his knees, the Prince wanders into the garden and, as his favourite companion – his Great Dane Bendicò – digs happily in a flowerbed, Fabrizio becomes conscious of a close, sickly atmosphere emanating from the decaying corpse of a Neapolitan soldier who has managed to struggle into the adjacent lemon grove to die. His slow, painful death mirrors the social change that is at the heart of the novel, as the Prince is forced to recognize the inevitable social rise of Sedàra, the uncouth, wily mayor of Donnafugata, where Fabrizio has a summer villa. The mayor, he realizes, has through chicanery become considerably richer than the Prince himself.

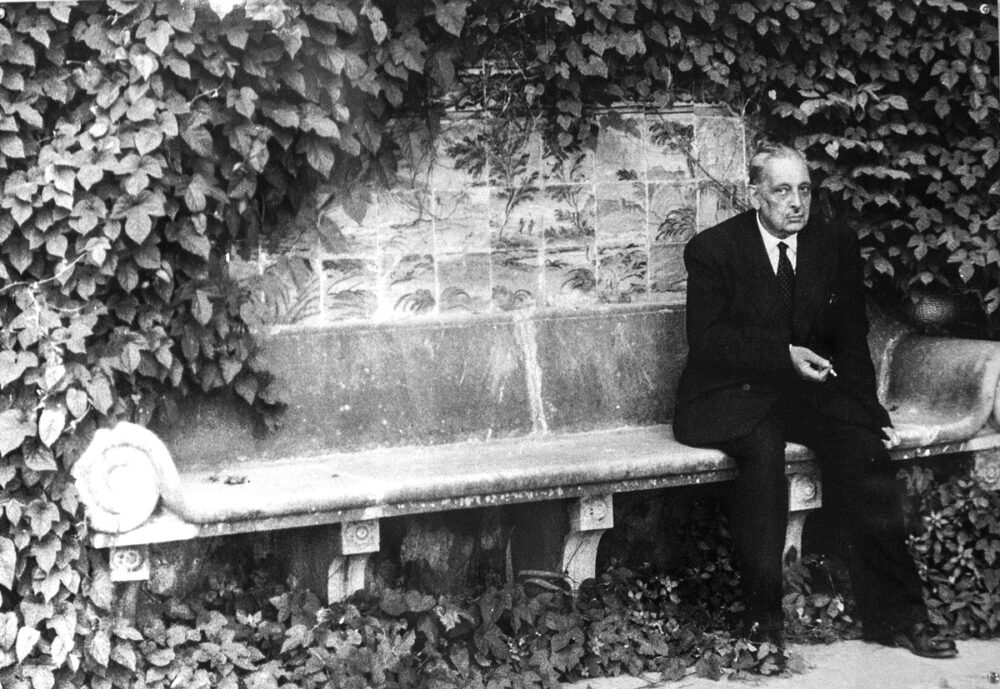

The Leopard was the single book written by Giuseppe Tomasi

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inRecently, the lack of anything worth watching on TV sent me, once again, to the DVD of Visconti’s lush 1963 film of Giuseppe Lampedusa’s The Leopard (1958). If one loves a book, the idea that a film version might be in a different way as satisfactory as the original seems a sort of betrayal. But at the very least I find it impossible to reread the book without Burt Lancaster’s Prince Fabrizio, Claudia Cardinale’s ravishing Angelica and Alain Delon’s handsome, selfregarding Tancredi illustrating the narrative as a most remarkable set of lithographs might.

The author of course provided his own vivid panorama before the film came along, and a reader with no previous sense of the barren, dusty landscape of Sicily and no knowledge of or special interest in the turmoil of Italian society during the Risorgimento does not have to read long before being immersed in the place and time of the novel, and understanding the creaking uncertainty and shock experienced by the society of which Prince Fabrizio is the head. We meet him and his family first at morning prayers in the vast family palace outside Palermo. Rising from his knees, the Prince wanders into the garden and, as his favourite companion – his Great Dane Bendicò – digs happily in a flowerbed, Fabrizio becomes conscious of a close, sickly atmosphere emanating from the decaying corpse of a Neapolitan soldier who has managed to struggle into the adjacent lemon grove to die. His slow, painful death mirrors the social change that is at the heart of the novel, as the Prince is forced to recognize the inevitable social rise of Sedàra, the uncouth, wily mayor of Donnafugata, where Fabrizio has a summer villa. The mayor, he realizes, has through chicanery become considerably richer than the Prince himself. The Leopard was the single book written by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, the only child of a grandee of Spain, Prince of Lampedusa, Duke of Palma di Montechiaro and Baron of Torretta, with a palace in Palermo. He completed Il Gattopardo in 1956, and before his death the following year saw it rejected by two publishers. Published posthumously it swiftly became a worldwide literary sensation. The English title, The Leopard, resonates but isn’t quite what Lampedusa meant. The gattopardo was a wildcat hunted to extinction in the nineteenth century; the author’s reference was clearly to the grandees of Sicilian aristocracy, forced to come to terms with the new Kingdom of Italy which was supported by a greedy, corrupt, unprincipled liberal bourgeoisie set on destroying the old Bourbon aristocracy. The Prince makes the early decision that it will be impossible to fight the social changes which he clearly foresees, and concentrates instead on saving what he can of his depleted finances by the marriage of the beautiful Angelica, daughter of the vulgar mayor, to his wayward nephew Prince Tancredi, who has happily fallen in love with her. There is a wonderful chapter celebrating the courtship of Tancredi and Angelica as they wander through the countless neglected rooms of the palace (like other chapters, so cinematic that it is no surprise that Visconti could not resist it); but the reader is left in no doubt that the marriage, though saving for a time the family’s finances, is doomed to be as unsatisfactory as that of the Prince himself, wed to a religious and puritanical wife. He regularly rides off to visit one of the local prostitutes, his expeditions less than satisfactorily excused by the company of the family’s priest. The portrait of Prince Fabrizio is comprehensive in its characterization of a man deeply troubled by the contradictions in which he finds himself enmeshed. His beloved Tancredi becomes a traitorous follower of the invading Garibaldi, and he knows that in encouraging Tancredi’s marriage to Angelica he is betraying his own favourite daughter, Concetta, who has always loved the young tearaway. Financially astute, he is also deeply sentimental, devoted to hunting and shooting. Out one day with a companion, he injures a wild rabbit and then picks it up and cradles it:the velvety ears were already cold, the vigorous paws contracting in rhythm, still-living symbol of useless flight; the animal had died tortured by anxious hopes of salvation . . . While sympathetic fingers were still stroking that poor snout, the animal gave a last quiver and died; Don Fabrizio and Don Ciccio had had their bit of fun, the former not only the pleasure of killing but also the comfort of compassion.The book has much to say about the parallel lines of reality and sentiment: Tancredi and his friends come straight from the killing of the battlefield to the drawing-room of the Prince’s palace, and there they offer carefully edited anecdotes of blood and thunder to the ladies. There is also much discussion of current Italian politics, with special reference to Sicily’s part in any possible solution to the muddle, and it must be admitted that there are lengthy passages which only a very determined reader is likely to read with fascinated interest. Fabrizio’s beloved dog Bendicò, distinguished by a glass eye, plays an essential part in the story – indeed in a letter to a friend the author asserted that he is ‘a vitally important character and practically the key to the novel’. The book, indeed, ends twenty-seven years after the Prince’s death in a scene where the aged Concetta realizes that an unpleasant smell in her rooms emanates from the skin of Bendicò, turned into a now moth-eaten rug. Thrown out of a window, ‘its form recomposed itself for an instant; in the air there seemed to be dancing a quadruped with long whiskers, its right foreleg raised in imprecation. Then all found peace in a heap of livid dust.’ The book’s publication caused a tremendous furore in Italy. The author’s view was clearly that of the Prince: ‘We were the Leopards, the Lions, those who’ll take our place will be little jackals, hyenas; and the whole lot of us, Leopards, jackals and sheep, we’ll go on thinking ourselves the salt of the earth.’ It was not a sentiment to please every reader, and it is not surprising that it irritated the Catholic Church, the Communist Party and the residual nobility of Sicily in equal measure. But within a few years it was recognized as one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 77 © Derek Parker 2023

About the contributor

Derek Parker has returned to England from Sydney, where he enjoyed the company of several subscribers to Slightly Foxed.