I’ve always thought journals and letters among the best of bedside books. The entries, for one thing, are just long enough, usually, to end as drowsiness begins to be irresistible. I first came across one of Horace Walpole’s letters in an anthology, and thought it was as entertaining as one of Byron’s. I looked out more of them; they too were as entertaining as Byron’s – maybe even more so. I had recently given up buying, volume by volume as they came out, the great Murray edition of Byron’s letters, on the grounds that they had become too expensive; a decision I now regret with inexpressible bitterness. But maybe there was an affordable collected edition of Walpole’s.

There was indeed. It was published by Yale and edited by W. S. Lewis, who had worked on the project for 46 years, and published the final 48th volume in 1983. I don’t know whether it’s now possible to find a complete set; if one could, it would I guess be astronomically expensive. I gave up the idea. But fortunately single volumes pop up here and there on the Internet, as indeed do excellent selections – my own favourite, by my own bedside, came from a bookshop found on iLibris, published in 1930 and a good-looking book as well as a good anthology.

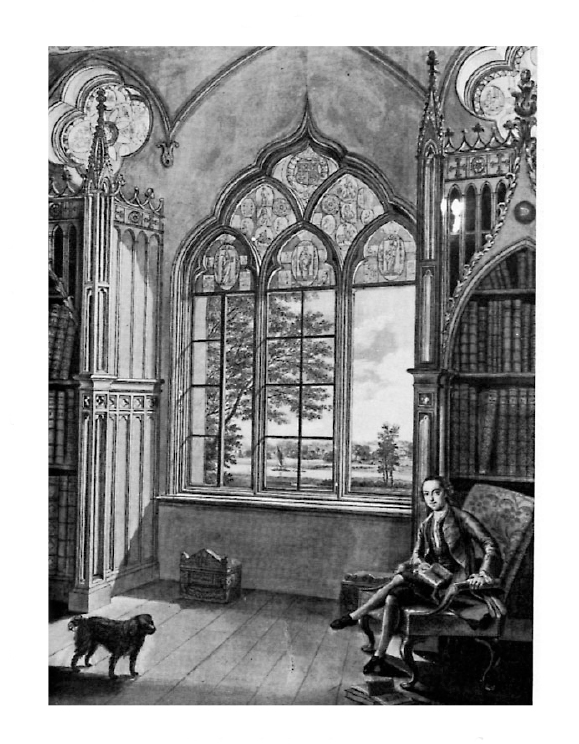

Most people, if they think of Walpole at all, remember him as the author of the Gothic horror story The Castle of Otranto – popular enough in its time, still readable and sometimes read. He’s also remembered for Strawberry Hill, the most famous house in Georgian England (open to the public now as it was in his own time, when he even set up an advance booking system). His Essay on Modern Gardening has its virtues. But the best of his life went into his letters. Sir Walter Scott called him ‘the best letter-writer in the English language’; Byron thought his letters ‘incomparable’ – and he knew something about writing a good letter.

The son of Sir Robert Walpole, Prime Minister under t

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inI’ve always thought journals and letters among the best of bedside books. The entries, for one thing, are just long enough, usually, to end as drowsiness begins to be irresistible. I first came across one of Horace Walpole’s letters in an anthology, and thought it was as entertaining as one of Byron’s. I looked out more of them; they too were as entertaining as Byron’s – maybe even more so. I had recently given up buying, volume by volume as they came out, the great Murray edition of Byron’s letters, on the grounds that they had become too expensive; a decision I now regret with inexpressible bitterness. But maybe there was an affordable collected edition of Walpole’s.

There was indeed. It was published by Yale and edited by W. S. Lewis, who had worked on the project for 46 years, and published the final 48th volume in 1983. I don’t know whether it’s now possible to find a complete set; if one could, it would I guess be astronomically expensive. I gave up the idea. But fortunately single volumes pop up here and there on the Internet, as indeed do excellent selections – my own favourite, by my own bedside, came from a bookshop found on iLibris, published in 1930 and a good-looking book as well as a good anthology. Most people, if they think of Walpole at all, remember him as the author of the Gothic horror story The Castle of Otranto – popular enough in its time, still readable and sometimes read. He’s also remembered for Strawberry Hill, the most famous house in Georgian England (open to the public now as it was in his own time, when he even set up an advance booking system). His Essay on Modern Gardening has its virtues. But the best of his life went into his letters. Sir Walter Scott called him ‘the best letter-writer in the English language’; Byron thought his letters ‘incomparable’ – and he knew something about writing a good letter. The son of Sir Robert Walpole, Prime Minister under the first two Georges, Walpole was provided by his father with a large income skimmed from the public purse, and was thus free to devote his time to whatever activity appealed to him – playing with Patapan or Tonton, his dogs, planning and executing the creation of his toy castle, writing his gothic romance and a few other books. He was a Whig MP for 27 years – for Callington, in Cornwall, which he never visited, then for Castle Rising, in Norfolk, and finally for King’s Lynn. He took politics seriously, without actually taking a serious active role in them. Setting down social gossip and scandal in fifty years of letters to a huge variety of friends was his main occupation and pleasure. A little man in a lavender suit, with ruffles and lace-frilled shirt, silver-embroidered white silk waistcoat, silk stockings and goldbuckled shoes, he found his way into every fashionable salon and knew everyone who was worth knowing: from members of the royal family and the government to the most beautiful and notorious women of the age – La Belle Jennings, Arabella Churchill, the Duchess of Kendal and Mrs Fitzherbert. He seems not to have been inordinately attractive: his voice was rough and his laugh forced and coarse, and for the second half of his life he was crippled with gout. His manners were formal but less than considerate – one of his dogs always joined him at table, sometimes accompanied by a pet squirrel. He adored dogs – a guest in a somewhat dull house, he was pleased that at least ‘there were two or three children, and two or three-and-forty dogs; I generally prefer both to what common people call Christians’. He was appalled at the general view of dogs complaining in 1760 thatWalpole attended most of the great royal occasions of his lifetime (as a boy he had kissed the hand of King George I and he lived to see the accession of George III). In November 1760 he sent one of his correspondents a long and vivid account of the funeral of George II, ‘the yeomen of the guard crying out for help, oppressed by the immense weight of the coffin’. Amid the solemnity appeared the Duke of Newcastle:in London the streets are a very picture of the murder of the innocents – one drives over nothing but poor dead dogs! The dear, good-natured, honest, sensible creatures! Christ! How can anybody hurt them? Nobody could but those Cherokees the English, who desire no better than to be halloo’d to blood – one day, Admiral Byng, the next Lord George Sackville, and today the poor dogs!

He fell into a fit of crying the moment he came into the chapel, and flung himself back in a stall, the Archbishop hovering over him with a smelling-bottle; but in two minutes his curiosity got the better of his hypocrisy, and he ran about the chapel with his glass to spy who was or was not there, spying with one hand, and mopping his eyes with the other. Then returned the fear of catching cold, and the Duke of Cumberland, who was sinking with heat, felt himself weighed down, and turning round, found it was the Duke of Newcastle standing on his train, to avoid the chill of the marble.

Such eccentricities delighted him – he was especially fond of the account of a small pew in Gloucester cathedral, ‘hung with green damask, with curtains of the same; a small corner cupboard, painted, carved, and gilt, for books in one corner, and two troughs of a birdcage, with seeds and water . . . It belongs to a Mrs Cotton, who, having lost a favourite daughter, is convinced her soul is transmigrated into a robin-redbreast. The chapter indulge this whim, as she contributes abundantly to glaze, whitewash and ornament the church.’

Royal and noble amours always entertained him. He watched with interest the progress of George II’s admiration for Elizabeth Chudleigh, who appeared at a Ranelagh masquerade as Iphigenia, ‘but so naked that you would have taken her for Andromeda’ – that was on the famous occasion when the witty Lady Mary Wortley Montagu remarked that Miss Chudleigh ‘was Iphigenia for the sacrifice, but so naked the high priest might easily inspect the entrails of the victim’. Walpole looked on as the king presented her with a 35-guinea watch, and later kissed her in public. She became the royal mistress, despite the protests of Augustus Hervey and the Duke of Kingston, concurrently her husbands.

Walpole never married, and it seems likely he was either homosexual or asexual – which did not prevent him from admiring a handsome woman. Marie Antoinette seems to have been his ideal: she ‘shot through the room like an aerial being, all brightness and grace and without seeming to touch earth . . . Hebes and Floras, and Helens and Graces, are street-walkers to her. She is a statue of beauty, when standing or sitting; grace itself when she moves . . . For beauty [at Versailles] I saw none, for the Queen effaced all the rest.’ He also much admired the Duchess of Richmond, ‘fair and blooming as when she was a bride’ despite the fact that she ‘takes care that the house of Richmond shall not be extinguished: she again lies in, after having been with child seven-and-twenty times’.

No one enjoyed a party more than Walpole, but he did become irritated if they went on too long: ‘Silly dissipation increases, and without an object’, he told Sir Horace Mann in 1777 – an American fashion, he fancied. ‘The present folly is late hours. Everybody tries to be particular by being too late. It is the fashion now to go to Ranelagh two hours after it is over. You may not believe this, but it is literal. The music ends at ten; the company go at twelve. Lord Derby’s cook lately gave him warning. The man owned he liked his place, but said he should be killed by dressing suppers at three in the morning.’ When he, Walpole, tried to engage a housemaid and asked why she wanted to leave her present place, she told him she ‘could not support the hours she kept; that her lady never went to bed till three or four in the morning. “Bless me, child,” I said, “why, you tell me you live with a bishop’s wife: I never heard that Mrs North gamed or raked so late.” “No, sir,” said she, “but she takes three hours undressing.”’

He never indulged in the great vice of the age, gambling, but happily reported its extremities: at White’s club, in 1750, ‘a man dropped down dead at the door, was carried in; the club immediately made bets whether he was dead or not, and when they were going to bleed him, the wagerers for his death interposed, and said it would affect the fairness of the bet’. Twenty-five years later, a young man ‘betted £1,500 that a man could live twelve hours under water; hired a desperate fellow, sunk him in a ship, by way of experiment, and both ship and man have not appeared since’. If he had a vice, if it is a vice, it was his love of fires, ‘the only horrid sight that is fine’. His servant was ordered to wake him at any news of a conflagration. In February 1755 (he told his friend Richard Bentley) he was awakened in the middle of the night, threw on his slippers and the fine embroidered suit he had taken off that evening, and dashed off toward St James’s.Like most men, Walpole grumbled at change – manners were becoming terse and coarse: ‘all paraphrases and expletives are so much in disuse, that I suppose soon the only way of making love will be to say “Lie down.”’ He took his old age gracefully, however, to the point when he was ‘an unfinished skeleton of seventy-seven, on whose bones the worms have left just so much skin as prevents my being nailed up yet’. He died in 1797 and, as the essayist Austin Dobson put it, ‘for diversity of interest and perpetual entertainment, for the constant surprises of an unique species of wit, for happy and unexpected turns of phrase, for graphic characterisation and clever anecdote, for playfulness, pungency, irony, persiflage, there is nothing in English like his correspondence.’I ran to Bury Street, and stepped into a pipe that was broken up for water. It would have made a picture – the horror of the flames, the snow, the day breaking with difficulty through so foul a night, and my figure, all mud and gold. It put me in mind of Lady Margaret Herbert’s providence, who asked somebody for a pretty pattern for a nightcap. ‘Lord!’ said they, ‘what signifies the pattern of a nightcap?’ – ‘Oh! Child,’ said she, ‘but, you know, in case of fire.’ Two young beauties were conveyed out of a window in their shifts. There have been two more great fires. Alderman Belchier’s house at Epsom, that belonged to the Prince [of Wales], is burnt, and Beckford’s fine house in the country, with pictures and furniture of a great value. He says, ‘Oh! I have an odd fifty thousand pounds in a drawer: I will build it up again: it won’t be above a thousand pounds a-piece difference to my thirty children.’

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 37 © Derek Parker 2013

About the contributor

Derek Parker lives in Sydney with his wife Julia; they have edited twelve anthologies of poems particularly suitable for each of the twelve signs of the Zodiac, just published in book form and as e-books.