Not too many years ago, it would have been unnecessary to explain who James Thurber was. His short story ‘The Secret Life of Walter Mitty’, published in 1947 in the New Yorker (where most of his writing first appeared), soon found an international audience, and despite the best efforts of Danny Kaye to kill it off in a truly appalling film, it remains one of the most adept pieces of comic writing of its time, with most of the classic Thurber trademarks, including his delight in inventing words: among them the pseudomedical terms ‘obstreosis of the ductal tract’ and ‘streptothricosis’, and the information that ‘Coreopsis has set in’.

Thurber was a country boy, born in Columbus, Ohio, in 1894. When I went there in the 1970s nobody had heard of him; now there is a statue, and 77 Jefferson Avenue is Thurber House, irresistible to any admirer who wants to see where his extraordinary family lived – the family he made famous for its eccentricity.

He had two brothers, and ill-advisedly volunteered to play William Tell with them. Missing the apple, an arrow shot out an eye. Among the results seems to have been his failure to take Ohio State University seriously, and instead to join the Columbus Dispatch in 1920 as a young reporter. Seven years later a friend, the author E. B. White, got him a job as editor on the famous New Yorker magazine (similar to Punch, but smarter and brighter and funnier). Within a few months he was writing for it. He set up home in New York, and apart from regular visits to Europe, never again left the city.

One of the most difficult things in the world is to describe a humourist to someone who hasn’t read him. Thurber’s view was pers

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inNot too many years ago, it would have been unnecessary to explain who James Thurber was. His short story ‘The Secret Life of Walter Mitty’, published in 1947 in the New Yorker (where most of his writing first appeared), soon found an international audience, and despite the best efforts of Danny Kaye to kill it off in a truly appalling film, it remains one of the most adept pieces of comic writing of its time, with most of the classic Thurber trademarks, including his delight in inventing words: among them the pseudomedical terms ‘obstreosis of the ductal tract’ and ‘streptothricosis’, and the information that ‘Coreopsis has set in’.

Thurber was a country boy, born in Columbus, Ohio, in 1894. When I went there in the 1970s nobody had heard of him; now there is a statue, and 77 Jefferson Avenue is Thurber House, irresistible to any admirer who wants to see where his extraordinary family lived – the family he made famous for its eccentricity. He had two brothers, and ill-advisedly volunteered to play William Tell with them. Missing the apple, an arrow shot out an eye. Among the results seems to have been his failure to take Ohio State University seriously, and instead to join the Columbus Dispatch in 1920 as a young reporter. Seven years later a friend, the author E. B. White, got him a job as editor on the famous New Yorker magazine (similar to Punch, but smarter and brighter and funnier). Within a few months he was writing for it. He set up home in New York, and apart from regular visits to Europe, never again left the city. One of the most difficult things in the world is to describe a humourist to someone who hasn’t read him. Thurber’s view was personal: English humour, he thought, treated the commonplace as if it were remarkable, American humour treated the remarkable as if it were commonplace. Another of his theories was that the best humour reflects ‘emotional chaos remembered in tranquillity’. That’s certainly true of a lot of his writing, especially about his own family, which is celebrated (if that’s the right word) in some of his best pieces. In its context, there’s nothing remarkable about his Aunt Sarah Shoaf, always convinced that she was going to be chloroformed in the night by burglars who had, she thought, been getting into her house every night for forty years.The fact that she never missed anything was to her no proof to the contrary. She always claimed that she scared them off before they could take anything, by throwing shoes down the hallway. When she went to bed she piled, where she could get at them handily, all the shoes there were about the house. Five minutes after she had turned off the light, she would sit up in bed and say ‘Hark!’ Her husband, who had learned to ignore the whole situation as long ago as 1903, would either be sound asleep or pretend to be sound asleep . . . so presently she would arise, tiptoe to the door, open it slightly and heave a shoe down the hall in one direction, and its mate down the hall in the other direction. Some nights she threw them all, some nights only a couple of pair.Meanwhile, brother Herman was singing ‘Marching through Georgia’ in his sleep, while first cousin Briggs, convinced he would cease breathing in the night, woke, came to the conclusion that he was suffocating, and broke a window to get some air; he was then attacked by the dog. Father, waking in a distant bedroom, heard the row and called, ‘I’m coming! I’m coming!’ Mother, hearing his mournful tone, shouted: ‘He’s dying!’ A normal night in the Thurber household. Eventually, the situation was ‘finally put together like a gigantic jigsaw puzzle . . . “I’m glad,” said mother, who always looked on the bright side of things, “that your grandfather wasn’t here.”’ Now if none of this sounds particularly funny, all I can do is tell you, it is. Much of the fun comes from the characters – most of whom seemed to gather around Thurber waiting to be immortalized: Gertie Straub, a family servant, who would come home in the early morning dead drunk, lurch around breaking things, and when Thurber’s mother shouted downstairs, ‘What are you doing?’ would inevitably reply, ‘Dusting.’ Or Della, whose way with the English language was uncertain, and who would ask, ‘Do you want cretonnes in your soup tonight?’ Occasionally, he allowed himself to get serious – as in his beautiful anti-war fable ‘The Last Flower’; but Thurber was always at his best when looking the human condition straight in the eye – or maybe sometimes to one side of it, like Muggs, one of his incomparable dogs. Muggs was rather like Hardy’s dog Wessex, who bit everyone who came to the house except Lawrence of Arabia. Muggs wouldn’t have hesitated; Aircraftsman Ross would have got it in the leg like everyone else. In old age, Muggs took to ‘seeing things’.

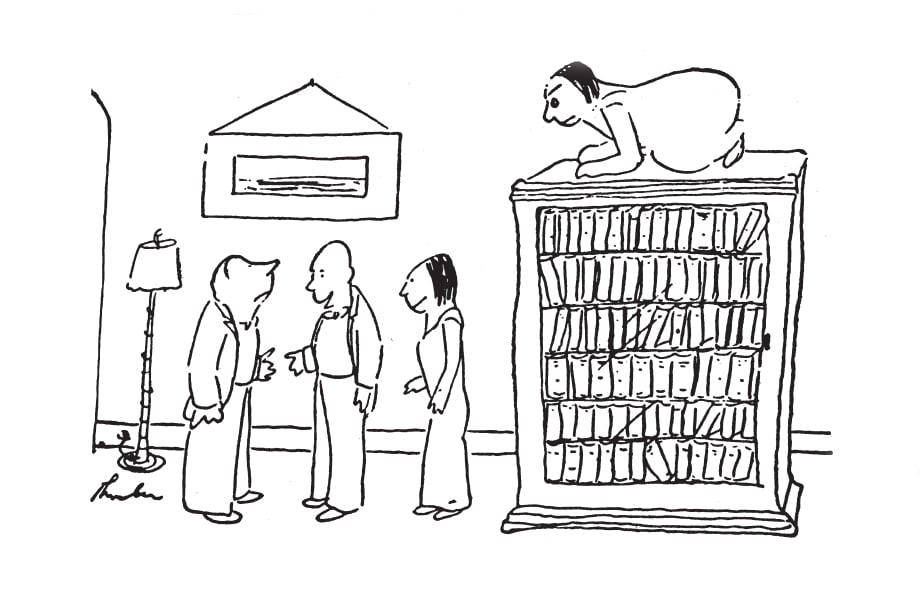

He would rise slowly from the floor, growling low, and stalk stiff-legged and menacing toward nothing at all. Sometimes the Thing would be just a little to the right or left of a visitor. Once a Fuller Brush salesman got hysterics. Muggs came wandering into the room like Hamlet following his father’s ghost. His eyes were fixed on a spot just to the left of the Fuller Brush man, who stood it until Muggs was about three slow, creeping paces from him. Then he shouted. Muggs wavered on past him into the hallway grumbling to himself but the Fuller man went on shouting. I think mother had to throw a pan of cold water on him before he stopped.These sketches didn’t come easy: Thurber rewrote every piece between twelve and twenty-four times, so that a 20,000-word story might have had 240,000 words spent on it before finally taking the shape he wanted. You can’t, of course, tell that they’ve been rewritten, and rewritten, and rewritten. Unquestionably some of them display some of the best American writing of the time. His ‘The Greatest Man in the World’ (clearly a portrait of Lindbergh) is marvellously wicked – and ‘The Macbeth Murder Mystery’ (a hilarious story about an American lover of detective stories who finds herself with nothing but Shakespeare’s play to read, and is determined to find out who really dunnit) is a winner: ‘Oh, Macduff did it all right – Hercule Poirot would have got him easily.’ In the end almost all his prose pieces were illustrated – readers demanded it. Thurber always denied being an artist, and indeed his drawings got into print almost by accident. A friend kept finding his doodlings on the floor at the New Yorker office where they worked, and took to going over them in ink and submitting them. Eventually, one was accepted. The drawings came from so far out of left field that their origin was often obscure even to Thurber himself. ‘My drawings have been described’, he once said, ‘as pre-intentional, meaning they were finished before the idea for them had occurred to me. I shall not argue the point.’ In one of the famous Paris Review interviews, he recalled one of the most celebrated, showing a naked woman crouching on top of a bookcase, right up near the ceiling. Her husband and two other women are in the room below, and the husband is saying, ‘That’s my first wife up there, and this is the present Mrs Harris.’ Make of that what you will. Thurber said he had started by drawing a woman at the top of a flight of stairs, but had got the perspective wrong, and so . . . Then, when he submitted it, Ross, the editor of the New Yorker, simply didn’t get it and rang up to ask if the woman was alive, stuffed or dead. Thurber did some research and a taxidermist told him one couldn’t stuff a woman, and his doctor said a dead woman couldn’t crouch on all fours, so she must be alive. Ross still didn’t get it, but he published the drawing, and it became one of Thurber’s most celebrated – almost as celebrated as the one of a couple in bed, with a seal perched on the bed-head above them. The caption is: ‘All right, have it your way – you heard a seal bark.’ It’s the innocent quality of the drawing that does the trick; Thurber drawings are economic, simple, naïve, with the utmost economy of line – and yet there is absolutely no question of mistaking them for anyone else’s. Remarkably, many of them were done when he was almost completely blind. By the end of the 1950s he had virtually lost the use of his single working eye, and had to draw on very large sheets of paper using a thick black crayon, or sometimes in white chalk on black paper. He would compose his prose in his head. His wife, looking at him across the dinner table, would often say, ‘Dammit, Thurber, stop writing!’ He made fun, naturally, even of the problems that his poor sight brought him. He wrote to a couple of friends relating how it took him two hours to drive himself and his wife home from dinner with them:

A peril of the night road is that flecks of dust and streaks of bug blood in the windshield look to me often like old admirals in uniform, or crippled apple women, or the front end of barges, and I whirl out of their way, thus going into ditches and fields and front lawns, endangering the life of authentic admirals and apple women who may be out on the roads for a breath of air before retiring . . .He had a series of glass eyes made for use during drinking sessions, each slightly more bloodshot than the one before. At about two in the morning he would slip the final one in: it had a little American flag on it. To the end he could outline one of his Thurber dogs – he was devoted to dogs throughout his life, his houses full of them. ‘If I have any beliefs about immortality,’ he once wrote, ‘it is that certain dogs I have known will go to heaven, and very, very few persons.’ One of his few descents into near-sentimentality is in his portrait of one of his dogs, Rex, ‘Snapshot of a Dog’, who in old age staggered in after a monumental fight which he had clearly lost.

He had apparently taken a terrible beating, probably from the owner of some dog that he had got into a fight with . . . He licked at our hands and, staggering, fell, but got up again. We could see that he was looking for someone. One of his three masters was not home. He did not get home for an hour. During that hour the bull terrier fought against death as he had fought against the cold, strong current of Alum Creek, as he had fought to climb twelve-foot walls. When the person he was waiting for did come through the gate, whistling, ceasing to whistle, Rex walked a few wobbly paces towards him, touched his hand with his muzzle, and fell down again. This time he didn’t get up.Note ‘ceasing to whistle’. Thurber could always pull a trick like that; but more often for the sake of humour than pathos. He knew as much about the art of writing as any of his peers, and cared more deeply about it than most. He got into terrible fights with contemporaries about the use of language, and most of them went away bruised. He really did fear that ‘the written word will soon disappear and we’ll no longer be able to read good prose like we used to could’. His life ended sadly: frustrated by no longer being able to draw or write, he descended into alcoholism and eventually almost madness. His wife would find him sitting in his study desperately making meaningless scrawls on copy paper. But let’s not leave him like that: let me recommend ‘Superghost’, the game he invented in his story ‘Do You Want to Make Something Out of It?’: you provide the letters at the centre of a word and challenge your opponent to extrapolate the complete word.

The Superghost aficionado is a moody fellow, given to spelling to himself at table, not listening to his wife . . . wondering why he didn’t detect, in yesterday’s game, that ‘cklu’ is the guts of ‘lacklustre’ and priding himself on having stumped everybody with ‘nehe’, the middle of ‘swineherd’.If stumped yourself, you can always get out of trouble by invention: Thurber, faced with ‘sgra’, finally came up with blessgravy: ‘A minister or cleric; the head of a family; one who says grace. Not to be confused with praisegravy, one who extols a woman’s cooking, especially the cooking of a friend’s wife; a gay fellow, a flirt, a seducer.’ Try it, and praisethurber.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 16 © Derek Parker 2007

About the contributor

Derek Parker was born in Cornwall, where he started life as a junior reporter on The Cornishman. After working in London for forty years in radio and TV and writing over 40 books (many in collaboration with his wife Julia) he now lives in Sydney. His latest book, Outback, tells the story of the European explorers who opened up the vast interior of Australia.