Soon after my Dublin grandfather’s death in 1946 several heavy teachests were delivered by rail to our Lismore home. My father gleefully pored over the numerous bulky tomes: the Works of Samuel Richardson in seven volumes (1785), a History of Free Masonry in five volumes, a rare numbered edition (No. 775) of the works of Henry Fielding in ten volumes with an introductory essay by Leslie Stephen, etc. etc. Being then aged 14 I was unexcited until I came upon a slim volume (foolscap octavo) by a mid-Victorian Englishwoman identifiable on p.1 as a kindred spirit. Ever since, Lucie Duff Gordon’s Letters from the Cape, written to a devoted husband and a worried mother, has been among my favourite accounts of travel.

Lucie Austin had enjoyed an unconventional education, including a few terms at a Hampstead co-ed where she added Latin to her collection of languages. As an 18-year-old she translated Niebuhr’s Studies of Ancient Greek Mythology, the first of many acclaimed translations. A year later she married Sir Alexander Duff Gordon, one of Queen Victoria’s assistant gentleman ushers who was to become a senior civil servant. Until 1860 this happy couple’s London home attracted literary lions (and a few lionesses) from near and far. Then Lucie developed an ominous cough and was advised to spend a year or so in the Cape Colony, a ‘cure’ often recommended to consumptives.

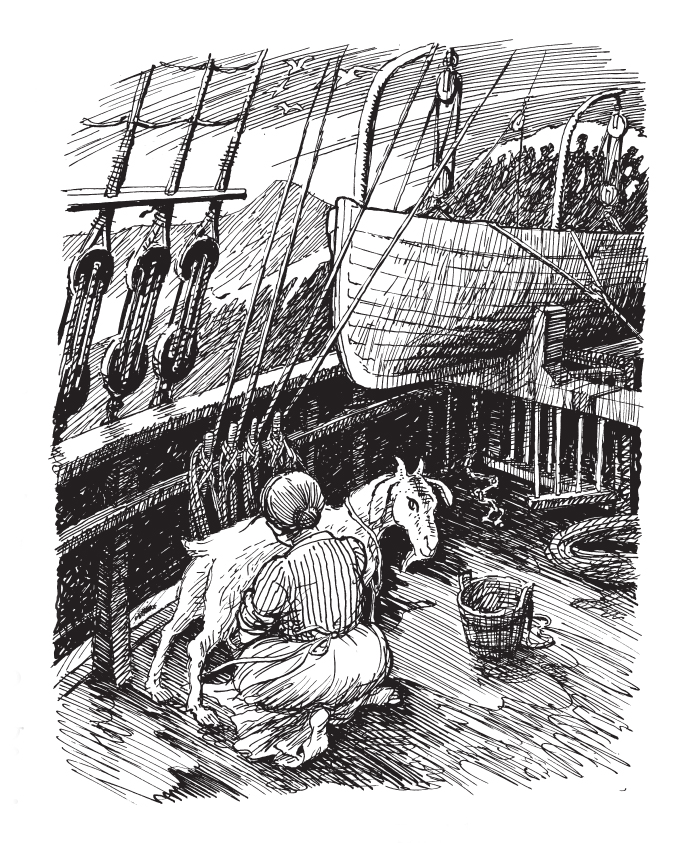

Characteristically, Lady Duff Gordon was averse to the newfangled steamers (‘you breathe coal-dust for the first ten days’). She therefore embarked for Cape Town on a tall-masted ship and had a ‘very enjoyable’ two-month voyage despite an uncommon share of ‘contrary winds and foul weather’. She shared a cabin with her maid Sally who neither grumbled nor gossiped and was always, like her mistress, amused and curious – ‘a better companion than many more educated people’. The third member of the party was a white goat who yielded

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inSoon after my Dublin grandfather’s death in 1946 several heavy teachests were delivered by rail to our Lismore home. My father gleefully pored over the numerous bulky tomes: the Works of Samuel Richardson in seven volumes (1785), a History of Free Masonry in five volumes, a rare numbered edition (No. 775) of the works of Henry Fielding in ten volumes with an introductory essay by Leslie Stephen, etc. etc. Being then aged 14 I was unexcited until I came upon a slim volume (foolscap octavo) by a mid-Victorian Englishwoman identifiable on p.1 as a kindred spirit. Ever since, Lucie Duff Gordon’s Letters from the Cape, written to a devoted husband and a worried mother, has been among my favourite accounts of travel.

Lucie Austin had enjoyed an unconventional education, including a few terms at a Hampstead co-ed where she added Latin to her collection of languages. As an 18-year-old she translated Niebuhr’s Studies of Ancient Greek Mythology, the first of many acclaimed translations. A year later she married Sir Alexander Duff Gordon, one of Queen Victoria’s assistant gentleman ushers who was to become a senior civil servant. Until 1860 this happy couple’s London home attracted literary lions (and a few lionesses) from near and far. Then Lucie developed an ominous cough and was advised to spend a year or so in the Cape Colony, a ‘cure’ often recommended to consumptives. Characteristically, Lady Duff Gordon was averse to the newfangled steamers (‘you breathe coal-dust for the first ten days’). She therefore embarked for Cape Town on a tall-masted ship and had a ‘very enjoyable’ two-month voyage despite an uncommon share of ‘contrary winds and foul weather’. She shared a cabin with her maid Sally who neither grumbled nor gossiped and was always, like her mistress, amused and curious – ‘a better companion than many more educated people’. The third member of the party was a white goat who yielded a pint of milk morning and evening – ‘a great resource, as the tea and coffee are abominable’. This Maltese citizen at first disliked African grass but on the return journey, in May 1862, was still giving milk – until suddenly she died, ‘to the general grief of the ship’. When, towards the end of her journey, Sir Alexander proposed publishing his wife’s letters, Lucie scoffed, ‘You must have fallen into second childhood to think of printing such rambling hasty scrawls . . . I never could write a good letter . . . only I fancy you will be amused by some of my “impressions”.’ Her mother, Sarah Austin, eagerly supported Sir Alexander, noting Lucie’s ‘frank and high-toned originality’. In an introduction to the first (1864) edition she emphasized, as the strongest motive for publication, the value of her daughter’s impressions as an antidote to the general tone of English travellers ‘[which] is too frequently arrogant and contemptuous’ because they make no attempt ‘to search out, under external differences, the proofs of a common nature’. In contrast, this English traveller took individuals as she found them. The Cape’s cultural cross-currents intrigued her. Near Newlands she observed a drainage scheme with an unexpected feature – ‘the foreman a Caffre, black as ink, six feet three inches high, and broad in proportion, with a staid, dignified air, and Englishmen working under him!’ In Wynberg an Irishwoman recalled shocking her puritanical Dutch host ‘by admiring the naked Caffres who worked on his farm. He wanted them to wear clothes.’ One would like to know more about this female admirer of naked males who sounds like a remnant of eighteenth-century Ireland. Lucie provides many glimpses of everyday life in a singularly multiracial colony. Here were Hottentots, Dutch, Caffres, Germans, Malays, English, Malagasies, French, Mantatees, Irish, Bosjeman, Bastaards and boers, who had not yet graduated to capital letters. Most Cape Bastaards were the offspring, in various combinations, of white sailors, black slaves and Hottentots. By the 1860s, in a territory slightly larger than Britain, this mixum-gatherum was collaborating and interbreeding with minimal friction between the settlers and the dispossessed. Yet only a half-century earlier Colonel John Graham had been leading his brand-new Cape Regiment on campaigns to burn all Caffre kraals and cultivated fields. Viewed from our neurotically fearful twenty-first century, the rural Cape Colony seems like the Garden of Eden before that incident with an apple. From Cape Town Lucie and Sally set off with Choslullah, their Malay driver, to follow rough mountain tracks through scattered villages. They stayed in ‘publics’ (not yet abbreviated to ‘pubs’) and Lucie often comments on the cleanliness of homes and persons. ‘The Hottentots are far cleaner in their huts than any but the very best English poor . . . Fleas and bugs are not half so bad as in France.’ Nobody locked their doors or kept watchdogs, never mind hiring security guards. At that date few English visitors ventured beyond Cape Town but to her mother Lucie explained, ‘I like this inn-life, because I see all the “neighbours” – farmers and traders – whom I like far better than the gentility of Cape Town.’ One afternoon, at the hamlet of Palmiet River, ‘We went into a neat little “public” and had porter and ham sandwiches, for which I paid 4s. & 6d. to a miserable-looking Englishwoman’ – an exorbitant price. Hours later they came upon a mud cottage, half-farm, half-inn, where an ancient German couple served an excellent supper of chops and bread and butter. That meal, and a tiny dark bedroom and a good breakfast, ‘cost ninepence for all’. Lucie invariably counted the pennies; she had to, hers was a journey undertaken cheerfully on a shoestring. In such lodgings, this non-memsahib was content to sleep on mattresses of maize straw and to ‘tub’ in what little muddy water might be available. She reproved herself for occasionally being extravagant enough to drink good claret – when the alternatives were ‘“New Wine” at a penny a glass, enough to blow your head off, and “Cape Smoke” (brandy, like vitriol) at ninepence a bottle’. Lucie lingered for a fortnight at Caledon where the octogenarian bachelor postman Heer Klein and his friend Heer Ley ‘became great cronies of mine’. Heer Klein recalled that many young slaves had prospered, when freed, and then been kind to those of their former owners who had fallen on hard times. Lucie particularly relished her crony’s personal reminiscences. Rosina, one of his slave-girls (‘handsome, clever, the best horse-breaker, bullock-trainer and driver in the district’), bore him two children, then had ‘six by another white man, and a few more by two husbands of her own race!’ In middle age she took to the bottle and, after emancipation in 1834, celebrated every anniversary of that event by standing outside Heer Klein’s window while loudly reading the statute. The Malays soon became Lady Duff Gordon’s favourite Cape inhabitants and back among the ‘gentility’ she raised many English eyebrows by frequently accepting Malay hospitality. The then fashionable form of Anglo-Islamophobia insisted that Mohammedans entertained Europeans only to poison them, so nobody expected an Englishwoman to pray one Friday in Cape Town’s Chiappini Street mosque.Returning to the mosque on the last evening of Ramadan, ‘I found myself supplied by one Mollah with a chair, and by another with a cup of tea . . . They spoke English very little but made up for it by their usual good breeding and intelligence.’ No doubt they had observed their guest’s failure to censure those penniless English emigrant girls who turned ‘Malay’ and professed Islam, ‘getting thereby husbands who know not billiards and brandy . . . They risk a plurality of wives but get fine clothes and industrious husbands.’ Lucie had recently been warned not to visit Muslims by a clergyman’s widow whose husband had gone mad three years after accepting a cup of coffee from a Malay. Scornfully she noted, ‘It is exactly like the medieval feeling about the Jews.’ Predictably, Lucie warmed to the Cape’s ‘very pleasant Jews’. Mr L. bred pigs on his model farm yet claimed to be ‘a thorough Jew in faith’ while choosing to say his prayers in English and not to ‘dress himself up in a veil and phylacteries’. He and his wife spoke of England as ‘home’ and cared no more than their neighbours for Jerusalem. But ‘They have not forgotten the old persecutions, and are civil to the coloured people, and speak of them in quite a different tone from other English colonists.’ While awaiting a suitable homebound ship (a weary six-week wait, costing ‘no end of money and temper’), Lucie was both exasperated and diverted by Christian denominational infighting. On 4 April she observed, ‘There is still altogether a nice kettle of religious hatred brewing here.’ The Anglican Bishop of Cape Town saw himself as ‘absolute monarch of all he surveys’. His chaplain had recently told a Mrs J. not to hope for salvation in the Dutch church, whose clergy had not been ordained – hence their administration of the sacraments could only lead ‘unto damnation’. An Admiral and his family were being anathematized for attending a bazaar in aid of the Wesleyan chapel, while an Irish maid at the Caledon Inn had been provoked by her bishop’s intolerance into marrying at the Lutheran church. By 16 May the good ship Camperdown had been a week at sea and Lucie was enjoying hundreds of frisking porpoises ‘glittering green and bronze in the sun’. Ten days later, near St Helena, ‘a large shark paid us a visit . . . a beautiful fish in shape and very graceful in motion . . . Last week we saw a young whale, a baby, about thirty feet long, and had a good view of him as he played around the ship’. This final letter held a warning: ‘I hope you won’t expect too much in the way of improvement in my health.’ Too soon, Lucie again had to flee the English climate. This time she settled in Luxor, perfected her Arabic and endeared herself to all her neighbours, especially the poor, the maimed and the exploited. During the next few years she made a close study of rural manners and customs and wrote her celebrated Letters from Egypt. In 1869 she died, was buried in Cairo’s English cemetery and was mourned for the rest of the century (and longer) by her many Egyptian friends. They referred to her as ‘the beautiful lady who was just and had a heart that loved Arabs’.A fat jolly Mollah looked amazed as I ascended the steps; but when I touched my forehead and said, ‘Salaam Aleikoom’, he laughed and said, ‘Salaam, Salaam, come in, come in.’ The faithful poured in, leaving their wooden clogs in company with my shoes . . . Women suckled their children and boys played as I sat on the floor in a remote corner. The chanting was very fine and the whole ceremony very decorous and solemn.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 38 © Dervla Murphy 2013

About the contributor

Dervla Murphy was born in Co. Waterford in 1931 where she still lives. Since 1963 she has been travelling by bicycle or on foot (usually beyond Europe) and returning to Lismore to write about her experiences. Her latest book, A Month by the Sea: Encounters in Gaza, was published by Eland in February.