Something half-remembered involving a writer locked in a tower, and a conviction that my first encounter – literary or otherwise – with the drink crème de menthe took place within its pages: these, until recently, were my hazy but fond memories of Dodie Smith’s I Capture the Castle. But within seconds of opening the novel again, I was reminded of why I had once loved it enough to read it several times a year. Cassandra Mortmain, its 17-year-old narrator, returned to me like an old friend and I realized that her voice – conspiratorial, self-deprecating and self-consciously literary – has been with me ever since I first encountered her. What hooked me about this book as a teenager was not so much the tale as its teller, a girl yearning, like me, to be two things at once – an adult and a writer.

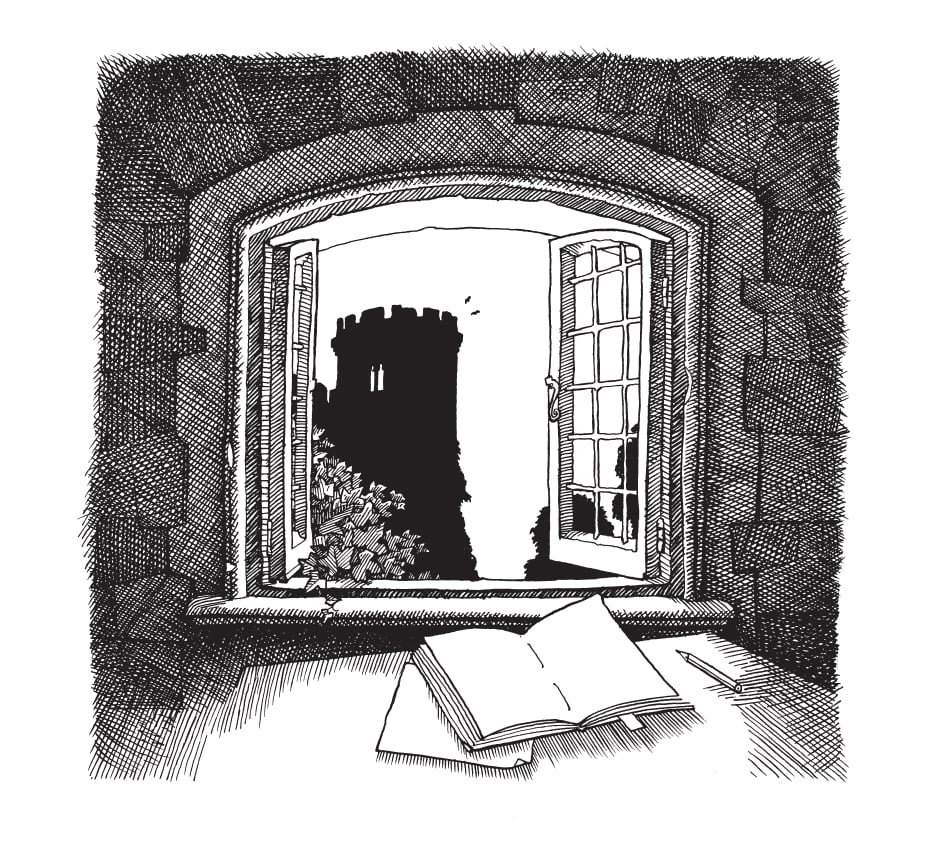

I Capture the Castle, Dodie Smith’s first novel, was published in 1948, though its quiet Englishness is of an earlier period, before the Second World War. Sisters Cassandra and Rose Mortmain live in the ruined splendour of an old castle complete with motte and bailey, mullioned windows, a moat and the mysterious Belmotte tower (‘sixty feet tall, black against the last flush of sunset’). Here also live their younger brother Thomas, their father James (a writer who no longer writes), their stepmother Topaz (former artists’ model and naturist), and a boy named Stephen Colly whom the family have semi-adopted but who fills the role of general servant.

As befits a novel about ‘two Brontë-Jane Austen’ type girls, the plot turns around the acquisition of husbands for Cassandra and Rose. James Mortmain, who once made money from a successful novel entitled Jacob Wrestling, is struggling to put pen to paper in order to revive the family fortunes. It is an era of traditional roles as far as middle-class women are conc

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inSomething half-remembered involving a writer locked in a tower, and a conviction that my first encounter – literary or otherwise – with the drink crème de menthe took place within its pages: these, until recently, were my hazy but fond memories of Dodie Smith’s I Capture the Castle. But within seconds of opening the novel again, I was reminded of why I had once loved it enough to read it several times a year. Cassandra Mortmain, its 17-year-old narrator, returned to me like an old friend and I realized that her voice – conspiratorial, self-deprecating and self-consciously literary – has been with me ever since I first encountered her. What hooked me about this book as a teenager was not so much the tale as its teller, a girl yearning, like me, to be two things at once – an adult and a writer.

I Capture the Castle, Dodie Smith’s first novel, was published in 1948, though its quiet Englishness is of an earlier period, before the Second World War. Sisters Cassandra and Rose Mortmain live in the ruined splendour of an old castle complete with motte and bailey, mullioned windows, a moat and the mysterious Belmotte tower (‘sixty feet tall, black against the last flush of sunset’). Here also live their younger brother Thomas, their father James (a writer who no longer writes), their stepmother Topaz (former artists’ model and naturist), and a boy named Stephen Colly whom the family have semi-adopted but who fills the role of general servant. As befits a novel about ‘two Brontë-Jane Austen’ type girls, the plot turns around the acquisition of husbands for Cassandra and Rose. James Mortmain, who once made money from a successful novel entitled Jacob Wrestling, is struggling to put pen to paper in order to revive the family fortunes. It is an era of traditional roles as far as middle-class women are concerned, and the Mortmain girls feel that their only way out of poverty is to marry well. When their landlords, wealthy American brothers Simon and Neil Cotton, turn up to take residence in their ancestral home, nearby Scoatney Hall, Rose sets about trying to win the heart of Simon the elder brother. Cassandra, meanwhile, is fighting off the attentions of Stephen Colly whilst keeping a worried, and then an envious, eye on Rose’s developing romance. So much for the tale, but what about its extraordinary teller? The premise is simple enough: Cassandra Mortmain is keeping a journal as a means of practising her speedwriting skills and assuaging boredom. Hers, she says, is a life in which nothing ever happens. Nevertheless, she has set herself an awesome task – to ‘capture the castle’ in much the way that a photographer ‘captures’ a scene, as fully and accurately as possible, in all its detail. But, like any budding writer – and more honestly than most – Cassandra realizes that transferring a living picture to paper is no easy matter. Like my teenage self (another diarist and secret would-be novelist), Cassandra often wrote for so long that her hand ached. And her questions about writing were my questions. Where do writers write best? How does a writer manage to find time to write about her life whilst still living it? What is the best way to convey a setting or describe an object? How does one write about things that are happening right now? And how, indeed, does one write about things that happened in the past (and about which you know the outcome), without giving the game away? Cassandra casts about for answers as she fills first the ‘Sixpenny Book’, then the ‘Shilling Book’ and finally the ‘Two Guinea Book’ with an abundance of daily detail. Memorably, she makes the reader aware of exactly where she is sitting as she creates her entries: ‘I am writing in the attic; I chose it because one can see Belmotte from the window.’ Or, on another occasion, ‘I am sitting on the ruins beyond the kitchen – where I sat with Neil, three weeks ago all but a day, after swimming the moat.’ The different vantage points around the castle are not only charming but also strategic. Moving around gives Cassandra the opportunity to stand outside events and comment dispassionately on her own family: ‘I like seeing people when they can’t see me, I have often looked at our family through lighted windows and they seem quite different, a bit the way rooms seen in looking-glasses do. I can’t get the feeling into words – it slipped away when I tried to capture it.’ At 17 I shared Cassandra’s annoyance with the way that events have a habit of encroaching upon the time you set aside to write. Ironically, as she writes – and almost, it seems, because she is writing – more things start to happen, life speeds up and her ‘capturing’ task becomes even more difficult. Although diarists always love to have events to write about, I recognized Cassandra’s frustration at the effort of recording days when a lot had happened: ‘I shall have to do the evening at Scoatney bit by bit, for I know I shall be interrupted – I shall want to be, really, because life is too exciting to sit still for long.’ I could understand too why, on one occasion, Cassandra guiltily confesses that she would rather write about Rose crying than go to comfort her. I Capture the Castle also taught me a thing or two about setting a scene. The backdrop of Cassandra’s story is a green and gentle England, complete with stately homes, inherited wealth, country pubs and quiet villages – a place that Dodie Smith apparently missed with a passion whilst living in America, which was where she wrote this book. How better to convey the special pleasures of England than by contrasting it with a country of vastly different culture and proportions? At one point Cassandra listens, eyes closed, to Neil Cotton describing a 3,000-mile car drive he made from California to New York. Having allowed herself to sense the ‘freedom and space of America’, she sees England, on opening her eyes, as an American would see it, ‘the fields and hedges and even the sky seemed so close they were almost pressing on me. Neil looked quite startled when I told him; he said that was how he felt most of the time in England.’ The closing-and-opening eye trick became a favourite of mine when trying to imagine how others would perceive a place that was familiar to me. The issue that puzzled me most as a budding writer was what to do with time – a concept so different on the page from real life. Cassandra experimented with the issue on my behalf, as it were. Sometimes she is writing at exactly the same moment that events are happening, ‘Oh! Oh my goodness! They’re here – the Cottons – they’ve just come round the last bend of the lane! Oh what am I to do? . . . They have gone past.’ This is an exciting but unsustainable narrative technique and she quickly resorts to the past tense, never forgetting, however, that in doing so, the writer must always hold back from saying too much too soon. ‘Oh, I long to blurt out the news in my first paragraph – but I won’t! This is a chance to teach myself the art of suspense.’ Through realizations like this, Cassandra taught me and, no doubt, many other young reader-writers too, ‘the art of suspense’. Finally, Cassandra helped rid me of over-poetic indulgence. There is a lesson to be learned from the way in which she struggles to capture in words natural objects such as the May blossom: ‘I once spent hours trying to describe it, but I only managed, “Frank-eyed floweret, kitten-whiskered,” which sticks in your throat like fish-bones.’ There is too much effort here, too much consciousness of what she is doing. Contrastingly, I saw that when she was trying less hard, her descriptions were far more effective. ‘How moons do vary! Some are white, some are gold, this was like a dazzling circle of tin – I never saw a moon look so hard before.’ Cassandra’s literary development is part of a wider theme in I Capture the Castle about the challenges of artistic expression. The novel oscillates between the daughter’s shows of verbal excellence and her father’s seemingly incurable writer’s block. James Mortmain’s inexplicable inability to start, never mind complete a new novel drives Cassandra and her brother Thomas finally to incarcerate him in Belmotte tower in an attempt to force him to compose. For me as a teenager – verbose to the point of self-indulgence – being unable to write seemed to be a terrible blight that almost justified such desperate measures. If the novel had been written by a less gifted author, the focus on Cassandra’s penning of the story could have been ponderous. But it is handled so deftly that it becomes the novel’s chief pleasure. As Cassandra matures, her journal becomes less of a schoolgirl notebook – with crude sections and snippets of essays on history – and more of a full-blown novel. And she senses this transformation with delight. ‘It took me three days to describe the party at Scoatney – I didn’t mark the breaks because I wanted it to seem like one whole chapter. Now that life has become so much more exciting I think of this journal as a story I am telling.’ Alongside her emotional development, Cassandra has, by the end, become a writer. There are some aspects of I Capture the Castle that may be difficult for a twenty-first-century audience to swallow: the shameless class prejudice against Stephen Colly – ‘always at the back of my mind, I know that it isn’t kind to be kind to Stephen; briskness is kindness’ – and the unquestioning reverence for America. But its many pleasures overshadow them. Among these are Cassandra’s first meeting with the American brothers, who discover her bathing in a tin bath in front of the fire, her arms green with dye; the episode in which Rose is mistaken for an escaped bear as she flees from a train wearing a long fur coat; and the delicious moment when Cassandra and Rose drink cherry brandy and (the oh-so sophisticated) crème de menthe under an enormous chestnut tree with the Cotton brothers. Add to these Topaz’s nude walks at midnight and the dinner party the Mortmain family throws for the Cottons at which the dinner table is made from a barn door taken off its hinges and the cloth from old brocade curtains – and you have a novel of delightful quirkiness. Yet it is not for the pleasures and eccentricities of plot and character that I return time and again to I Capture the Castle, but for its fascinating commentary on writing. As yet, I haven’t managed to write my great novel, so perhaps I am still hoping to pick up something from the way in which Cassandra’s journal changes – almost imperceptibly – from an artless exercise in speedwriting into something infinitely more subtle and shrewd – a work that has become literary.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 19 © Ruth Symes 2008

About the contributor

Ruth Symes lives in Manchester and is a freelance writer and editor. She has published academic books and articles on cultural history, popular articles on genealogy and some literary criticism. She has even managed one or two poems.