Back in the days when I used to read to my son at bedtime I was very struck by something Janet Adam Smith said in her introduction to The Faber Book of Children’s Verse. You will find, she said, that poems you learn when you’re young remain with you far longer than those you learn later. So in addition to ‘giving pleasure now’, she hoped her collection would ‘stock up the attics of your mind with enjoyment for the future’.

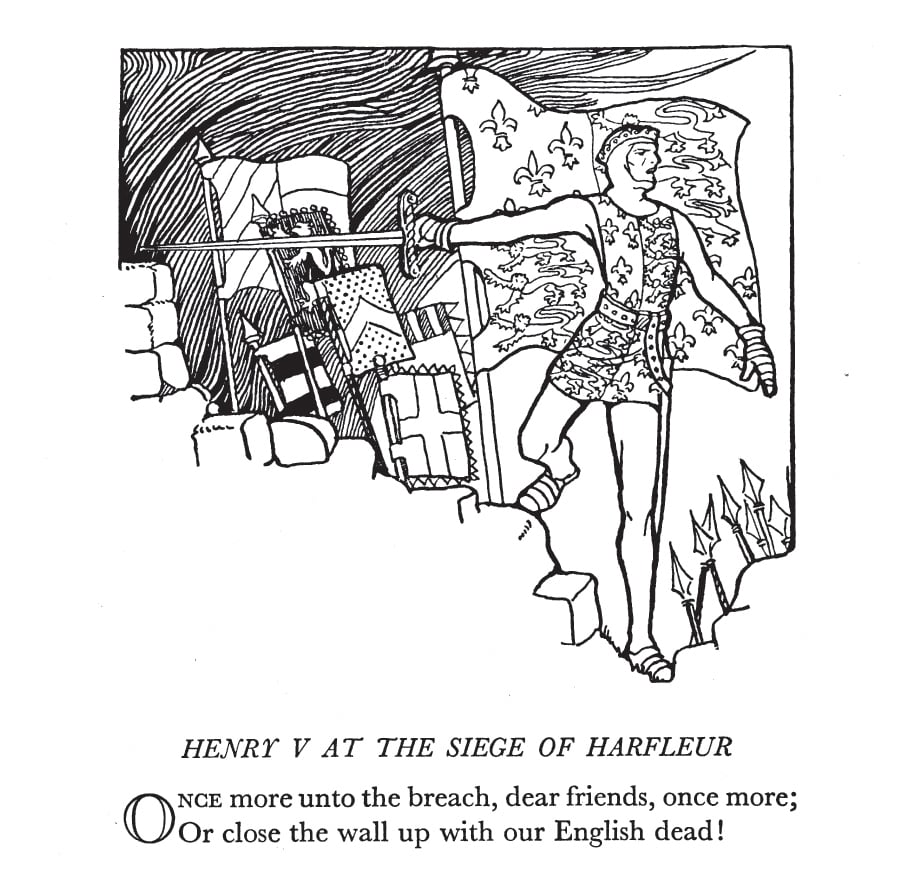

Oddly enough it was thanks to my wife’s discovery recently in a real attic that I was able to test Miss Adam Smith’s theory. Nestling in a box full of bric-à-brac was her father’s copy of The Dragon Book of Verse, a book I had last opened about sixty years ago at my prep-school, where it was used for a weekly exercise called ‘Rep’. He had bought it second-hand for 2/6d during the year he spent at Oxford before being called up. Before that it had belonged to a boy at St Edward’s, Oxford, who had coloured in many of the quaint illustrations.

For some of you the Dragon Book will need no introduction. It is as redolent of the classroom as Kennedy’s Latin Primer, Marten and Carter’s history books and, on a lighter note, 1066 and All That and Down with Skool! But I wonder how many people could name the Dragon Book’s editors? They were both called Wilkinson, as indeed was the Worcester College don whose ‘valuable assistance’ they acknowledge in the Preface. So presumably they were all related? Well, no. Nor were the two editors lifelong colleagues. For while W. A. C. Wilkinson – always known as ‘Wilkie’ – spent thirty-four years at the Dragon prep-school, Noel Wilkinson taught there for only four years, leaving in 1935, the year the Dragon Book appeared.

What the Wilkinsons shared was a love of poetry and the urge to pass it on to their pupils in an unusually enlightened manner. Learning poetry, they believed, ‘should be a delight and not a dreary task’. So rather than forcing a form to learn long poems ‘week by week, verse by verse’, they suggested that ‘more often than not’ pupils should be allowed to choose for themselves which poems to learn. I’m pretty sure this wasn’t the case at my school, but I was one of the lucky ones for whom memorizing a poem – or an irregular verb – was not a struggle.

Understanding what one learnt was more of a challenge. But the Wilkinsons argued, correctly I think, that young people don’t have to understand a poem to appreciate its beauty. Take ‘The Owl Song’ from Love’s Labour’s Lost – as earthy, it now seems to me, as a peasant painting by Bruegel. Even then it struck a chord that was not dimin-ished by my failure to register that �

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inBack in the days when I used to read to my son at bedtime I was very struck by something Janet Adam Smith said in her introduction to The Faber Book of Children’s Verse. You will find, she said, that poems you learn when you’re young remain with you far longer than those you learn later. So in addition to ‘giving pleasure now’, she hoped her collection would ‘stock up the attics of your mind with enjoyment for the future’.

Oddly enough it was thanks to my wife’s discovery recently in a real attic that I was able to test Miss Adam Smith’s theory. Nestling in a box full of bric-à-brac was her father’s copy of The Dragon Book of Verse, a book I had last opened about sixty years ago at my prep-school, where it was used for a weekly exercise called ‘Rep’. He had bought it second-hand for 2/6d during the year he spent at Oxford before being called up. Before that it had belonged to a boy at St Edward’s, Oxford, who had coloured in many of the quaint illustrations. For some of you the Dragon Book will need no introduction. It is as redolent of the classroom as Kennedy’s Latin Primer, Marten and Carter’s history books and, on a lighter note, 1066 and All That and Down with Skool! But I wonder how many people could name the Dragon Book’s editors? They were both called Wilkinson, as indeed was the Worcester College don whose ‘valuable assistance’ they acknowledge in the Preface. So presumably they were all related? Well, no. Nor were the two editors lifelong colleagues. For while W. A. C. Wilkinson – always known as ‘Wilkie’ – spent thirty-four years at the Dragon prep-school, Noel Wilkinson taught there for only four years, leaving in 1935, the year the Dragon Book appeared. What the Wilkinsons shared was a love of poetry and the urge to pass it on to their pupils in an unusually enlightened manner. Learning poetry, they believed, ‘should be a delight and not a dreary task’. So rather than forcing a form to learn long poems ‘week by week, verse by verse’, they suggested that ‘more often than not’ pupils should be allowed to choose for themselves which poems to learn. I’m pretty sure this wasn’t the case at my school, but I was one of the lucky ones for whom memorizing a poem – or an irregular verb – was not a struggle. Understanding what one learnt was more of a challenge. But the Wilkinsons argued, correctly I think, that young people don’t have to understand a poem to appreciate its beauty. Take ‘The Owl Song’ from Love’s Labour’s Lost – as earthy, it now seems to me, as a peasant painting by Bruegel. Even then it struck a chord that was not dimin-ished by my failure to register that ‘keel’ – as in ‘When greasy Joan doth keel the pot’ – did not mean scour, but stir. In fact it wasn’t until I reopened the book and read the editors’ explanatory footnote that I realized my mistake. ‘No book I have ever owned has given me more pleasure or, I believe, more profit,’ wrote the poet and academic Jon Stallworthy, an Old Dragon himself, of this anthology. To him it was ‘a period piece revealing of British middle-class attitudes between the wars’. Well, eighty plus years ago I suppose it was still just possible to believe that God was an Englishman. The Empire, lest we forget, was by then even larger than it had been under Queen Victoria. But I wonder if the presence of so many martial poems – ‘Horatius’, ‘Lepanto’, ‘The Revenge’ – was less a reflection of the ‘imperial aspirations’ Stallworthy identifies than of their harmony, the interplay of rhythm and metre that makes you want to read them aloud. Is there a more rousing opening to a poem than Chesterton gives ‘Lepanto’? – ‘White founts falling in the courts of the sun/And the Soldan of Byzantium is smiling as they run’. Closely followed by the first two lines of Byron’s ‘The Destruction of Sennacherib’: ‘The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold/And his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold’. That said, my early immersion in poetry that sang left me deaf to the appeal of what Edmund Wilson called ‘shredded prose’, his term for what was written by modern poets who had given up on verse. I know I should try reading it aloud, but I can’t be bothered to make the effort. And whatever its merits, it can’t be as easy to learn as lines that rhyme and scan. Jon Stallworthy also notes that it took him a while to realize how many poems in the anthology offered lessons in dying. One such was Rupert Brooke’s ‘The Soldier’, particularly cherished by my headmaster, like Brooke (and Stallworthy) an Old Rugbeian: ‘If I should die, think only this of me:/That there’s some corner of a foreign field/That is forever England . . .’ Many years later, when writing a radio series on Appeasement, I learned that in the Thirties irreverent schoolboys gave a pert response to Brooke’s exhortation: ‘He did, and we don’t.’ Such cheek would not, I’m sure, have gone unpunished at the time by the editors; but based in Oxford they must have been aware that many of the Auden generation (as it had yet to be dubbed) were deaf to the appeal of King and Country. Could this explain why they include only three poems by Kipling – then, I believe, more popular in Nazi Germany than in Great Britain – and nothing by Newbolt, the plucky public schoolboy’s laureate? Housman is another notable omission. Perhaps he was considered too pagan. And yet what could be more pagan than this? – ‘Golden lads and girls all must/As chimney-sweepers, come to dust’. Or this? – ‘Sceptre and Crown/Must tumble down/And in the dust be equal made/With the poor crooked scythe and spade’. Or this? – ‘The paths of glory lead but to the grave’. The writing was on the wall, all right, but aged 13 with your life before you, you could be forgiven for ignoring it. There are no prizes for guessing that Shakespeare, with thirty-four, has the highest number of entries. For this I am especially grateful because I’ve not seen many of his plays and if I can quote snatches of his verse and recognize a whole lot more, it’s thanks to the Dragon Book. How strange to think that I once won a prize for declaiming Hamlet’s soliloquy and was soundly beaten for calling one of the assistant masters a ‘lean and slipper’d pantaloon’. Another master, hearing me exaggerate my exploits on the rugger field, said I was far too young to start remembering ‘with advantages’, a caution I tried, with some success, to heed. Browning, whose ‘The Lost Leader’ every political correspondent I’ve ever read seems obliged to invoke at least once, is well represented, and so too is Tennyson, who I’d forgotten wrote ‘The Brook’ (‘I come from haunts of coot and hern’). Like my scapegrace contemporary, Nigel Molesworth, the ‘curse of st custards’, I’ve never been able to remember the third line of this, echoing his version: ‘and-er-hem-er-hem-the fern’. Molesworth, for whom ‘peotry [sic] is sissy stuff that rhymes’, gives qualified approval to ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’, unaccountably missing here. I thought ‘Jerusalem’ was missing too, only to find it listed as Part of the Preface to Milton, the prosaic title Blake gave it, which was certainly news to me. I must also admit how chastening it’s been to encounter so many lines derivation of which I appear to have forgotten – if indeed I registered them in the first place. Take, for instance, the ‘sneer of cold command’. What a wonderful expression, I thought, when I came across it in an essay. Was it in quotes? Maybe not. But even if it was I couldn’t have told you that it came from ‘Ozymandias’. Again, if you’d asked me who wrote, ‘But westward, look, the land is bright!’ I’d have answered Churchill, whereas in fact it was Arthur Hugh Clough. On the other hand we were certainly not encouraged to speculate about this line from Ovid’s Amores that Marlowe gives to Dr Faustus: ‘O lente, lente currite, noctis equi.’ In those days we didn’t receive official notice of the facts of life until our last day at school, so to learn that this was the poet praying for time to stand still so he could spend longer in bed with his mistress would have let the cat out of the bag. Had the Wilkinsons heard of Auden, then teaching at a Quaker prep-school near Malvern? Already hailed by Eliot as ‘one of the four or five living poets worth quarrelling about’, he was probably a little too outré to be included. And yet there was nothing outré about Auden’s theories on poetry and the young. ‘Do not enlarge on its beauties, but see that the vocabulary is understood . . . They will learn more about the meaning of poetry by writing it, than by any explanation you can give.’ Many years later, when interviewed by the Paris Review, he said, ‘If I had to teach poetry, I would concen-trate on prosody, rhetoric, philology and learning poems by heart.’ By then, rote learning, as its detractors termed it, was regarded as oppressive. Now we’re told it’s okay again, given the seal of approval by Salman Rushdie at last year’s Hay Festival. He called it a ‘lost art’ that enriches your relationship with language – ‘as any fule kno’, I am tempted to add. How much of what I learned as a boy have I retained? Well, rather more than anything I’ve tried to learn since, so Janet Adam Smith was right. But not as much as I’d have hoped, though of course it all comes back to me as soon as I Iook at the page, as is also the case with The Book of Common Prayer, another schoolroom text that was recited more often than read. From both I learned to appreciate, unconsciously but abidingly, the beauty of our native tongue. Asked to choose a favourite when I was young I’m sure it would have been something stirring like ‘Once more unto the breach’ or ‘Horatius’. Sixty years on I have lived longer than most of the poets in the anthology and, as the shadows start to lengthen, it is the elegiac that takes my fancy. Whether by accident or design there are, on the same page, two Shakespearian speeches that fit the bill: Macbeth’s meditation on the death of Lady Macbeth and Prospero’s ‘Valediction’. I heard the last recently at the memorial service for a great man and it took my breath away.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 56 © Michael Barber 2017

About the contributor

Michael Barber would like to thank Gay Sturt, the Dragon School’s archivist, for her help with this article.