When a people disappears, they say the last thing to be forgotten is its food. You might not teach your children your mother tongue, but the chances are you’ll still cook them your mother’s recipes.

Thessaloniki today seems a thoroughly Greek place – all Byzantine churches and pork skewers. But at the turn of the twentieth century the Ottoman port then called Salonika was a very different city. Half its inhabitants were Sephardic Jews, who had arrived in the area after their expulsion from Spain in 1492. They still named their synagogues after their lost Iberian homeland – Aragon, Catalan – and they spoke Ladino, a Hebrew-inflected dialect of medieval Spanish. The rest of the townsfolk were a mix of Turkish-speaking Muslims and Greek and Bulgarian Christians who lived in different districts and worked in different trades. So long as all obeyed the Sultan’s laws and paid his taxes, the empire’s authorities did not care whether their subjects shared Ottoman values or were culturally integrated. Salonika was multicultural avant la lettre.

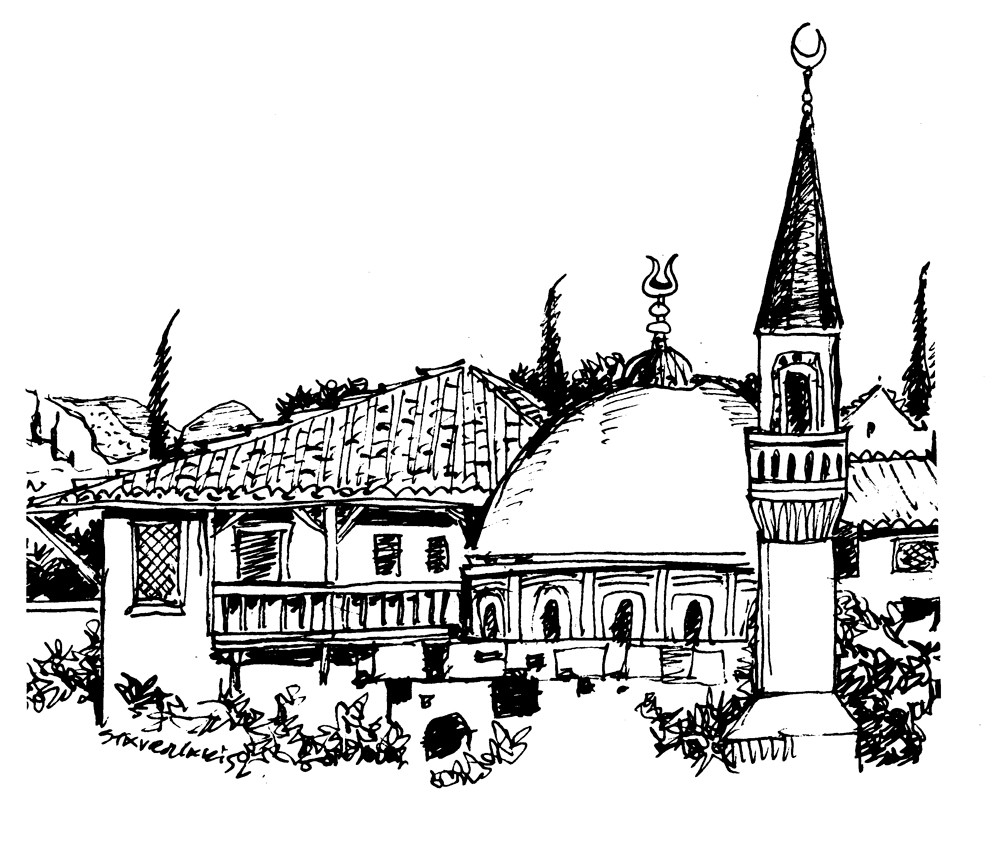

In the opening pages of Salonika: A Family Cookbook, by Esin Eden and Nicholas Stavroulakis, the latter calls the old city

an ancient house with many rooms, shared by different families whose paths only crossed in darkened corridors . . . Some rooms were full of light and open to the changes that were taking place in the world about this house, but others were dark, cradling hidden memories and events that were seldom, if ever, brought to light.

Now, the reader might raise a sceptical eyebrow at the words ‘family cookbook’. Personally, they make me think of spinsterly great-aunts with a taste for self-publishing. This is no jam-making memoir, however: it’s a last culinary record of a lost culture, and a window into a dark, tightly shuttered room. Esin Eden is a well-known Turkish actress, and her family – whose recipes

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inWhen a people disappears, they say the last thing to be forgotten is its food. You might not teach your children your mother tongue, but the chances are you’ll still cook them your mother’s recipes.

Thessaloniki today seems a thoroughly Greek place – all Byzantine churches and pork skewers. But at the turn of the twentieth century the Ottoman port then called Salonika was a very different city. Half its inhabitants were Sephardic Jews, who had arrived in the area after their expulsion from Spain in 1492. They still named their synagogues after their lost Iberian homeland – Aragon, Catalan – and they spoke Ladino, a Hebrew-inflected dialect of medieval Spanish. The rest of the townsfolk were a mix of Turkish-speaking Muslims and Greek and Bulgarian Christians who lived in different districts and worked in different trades. So long as all obeyed the Sultan’s laws and paid his taxes, the empire’s authorities did not care whether their subjects shared Ottoman values or were culturally integrated. Salonika was multicultural avant la lettre. In the opening pages of Salonika: A Family Cookbook, by Esin Eden and Nicholas Stavroulakis, the latter calls the old cityNow, the reader might raise a sceptical eyebrow at the words ‘family cookbook’. Personally, they make me think of spinsterly great-aunts with a taste for self-publishing. This is no jam-making memoir, however: it’s a last culinary record of a lost culture, and a window into a dark, tightly shuttered room. Esin Eden is a well-known Turkish actress, and her family – whose recipes these are – were members of Salonika’s strangest and most secretive sect. They called themselves Ma’aminim or Believers; to the rest of the world they were Dönme, the Turkish for ‘turncoats’. The Dönme were the Salonika-based followers of a seventeenth-century rabbi and self-proclaimed Messiah, Sabbatai Zevi. In the autumn of 1666, threatened by the Sultan with impalement, Sabbatai purchased his life by publicly converting to Islam. Thousands of his devotees interpreted this as a test of their faith and followed him into apostasy, but they continued to observe Jewish customs behind closed doors, mixing elements of Sufism and the Kabbalah with Sabbatai’s own mystical teachings. Each individual had two names: a Turkish name used in the outside world, and a Hebrew name revealed only to intimate acquaintances. According to the historian Gershom Scholem, there even exists strong evidence that – among their various ecstatic rites – the Dönme practised ritual wife-swapping. Though untraditional in more ways than one, they also had the city’s best schools, and by the turn of the twentieth century the 10,000 Dönme were one of the most highly educated and secular of Salonika’s communities. Photographs of Eden’s relatives show sensitive men in tall starched collars engrossed in the latest European fiction – Wildean dandies with olive skin and improbable moustaches. Dönme women were also some of the most liberated in the empire. In Eden’s family, ‘all of them were fluent in French, German and, of course, Osmanli [Ottoman Turkish], and the latest editions of novels and poetry were always appearing in the house’. As for Nicholas Stavroulakis, Eden’s co-author and illustrator, a photograph on the back cover shows him half-shrouded in darkness, his one visible eyebrow raised at the camera. An artist, a scholar and a founder of Greece’s Jewish Museum, he has rescued a Cretan synagogue from ruin, and there in advanced old age he presides over a congregation which numbers as many gentiles – drawn there out of sheer affection for him – as it does Jews. His life’s work has been to keep alive the memory of Greece’s cosmopolitan past, and he lurks in the acknowledgements pages of every book to have been published on Salonika or on Ottoman Jewry over the past few decades. The author photograph has him at his desk, a sort of rabbinic monk-scribe – his task to remember, to record and to illuminate. Some of the Dönme recipes look Greek: moussaka, stuffed vine leaves and egg-and-lemon sauces. Clearly Turkish are the kapama meats steamed with onion under lettuce leaves, and rice pilafs named after officers of the Janissary corps. I started by having a stab at an old Sephardic starter, huevos en haminados – hard-boiled eggs, simmered for hour after hour with onion skins, coffee grounds and used tea leaves until they’re stained a deep brown. They looked intriguingly pointless. The result: nutty, slightly fleshier-than-normal hard-boiled eggs. Perfectly nice, but nothing to write home about. Other Salonikan Jewish classics include fish in walnut sauce, and meatballs stewed in sweet green plums with the appealing name of bobotas. But the cookbook isn’t just a collation of Greek, Turkish and Sephardic dishes. Dönme cuisine also gives a direct insight into religious practices kept so tightly under wraps that it was not until the 1930s that one of their miniaturized, handwritten prayer books fell into an outsider’s hands. Sabbatai Zevi had instructed his followers to observe all the rituals of Islam, so there are kebabs for after sunset during Ramadan and mourning sweets for Ashura, which commemorates the deaths of Mohammed’s grandsons Hasan and Husayn. Ashura was particularly important to the Dönme, for whom Sabbatai was the latest incarnation of the divine spirit that Shi’a Muslims also claim passed down from Mohammed to his successors. Many of the Sephardic recipes have been modified to cook meat with butter, in defiance of Jewish dietary laws. Sabbatai claimed that his anointment as Messiah ushered in a new age, in which the written law of the Torah was revoked and what was forbidden became obligatory – hence also his followers’ unorthodox sexual behaviour. But cooking meat with dairy is also a clear Turkish influence: Jews are traditionally forbidden from mixing the two, and Greek Christians rarely cook in anything but olive oil. Just as the Dönme had to turn Turk, so did their Sephardic cuisine. Not much is left of old Salonika or the Dönme. Greece annexed Salonika in 1912. Under the terms of the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, the country expelled its Muslims in exchange for Turkey’s Orthodox Christians, and the Dönme were shipped off with them – notwithstanding their protestations that they were not true Muslims. Mostly settling in Istanbul, they quickly became a favourite subject for conspiracy theorists, and fear and isolation drove them to assimilate into mainstream Turkish society. Meanwhile, back in Salonika – by now renamed Thessaloniki – the Holocaust would be the final step in the city’s becoming homogeneously Greek. When Esin Eden travelled for the first time to her parents’ home,an ancient house with many rooms, shared by different families whose paths only crossed in darkened corridors . . . Some rooms were full of light and open to the changes that were taking place in the world about this house, but others were dark, cradling hidden memories and events that were seldom, if ever, brought to light.

On the Asian side of Istanbul, however, in the cemetery at Bülbülderesi – the Valley of the Nightingales – there are gravestones decorated with photographs of smartly dressed, sensitive-looking Turks, and with delicate carvings of butterflies. Their descendants, presumably, still live in the city. If any are reading this, do get in touch.the old great houses had been torn down and the gardens destroyed. Gone were the huge walnut trees that provided the nuts for fish recipes and Nuriye’s sweets all through the year . . . It was all gone.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 54 © Constantine Fraser 2017

About the contributor

Constantine Fraser is a postgraduate at the LSE. He spends much of his spare time conducting research into Eastern Mediterranean cuisine.