Notes from Town and Country

From Hazel, Highbury, 24 July 2020

On Sunday afternoon we set out for a walk in what is to me one of the strangest green spaces in this part of London, Abney Park Cemetery. Hidden behind the chic little boutiques and coffee shops of Stoke Newington Church Street, its 30-acre site originally formed part of the grounds of Fleetwood House and Abney House, both built in the 1600s and now demolished, one of which was lived in from 1734 until his death in 1748 by the preacher and hymn writer Isaac Watts.

Engravings of the time show both houses set in idyllic rural parkland dotted with sheep and ancient trees. But during the first half of the nineteenth century the population of London doubled and the city was running out of space to bury the dead. Overcrowded graveyards were polluting the water supply and causing epidemics, and in 1832 one of the many bills passed in that year of reform encouraged the establishment of private cemeteries in what were then the London suburbs. Out of this came London’s seven great Victorian garden cemeteries which include Highgate and Kensal Green, and, laid out in 1840, Abney Park. It was unique in being the only one not formally consecrated as a burial ground. With few exceptions no one has been buried there since 1978, when the local council took it over.

The cemetery was originally planned as an arboretum, planted by a local firm with 2,500 varieties of trees and plants and incorporating the elm and yew walks from the original park. At its centre is a disused Gothic Revival chapel from which woodland paths radiate to the outer circles. The carriage entrance, with grand gates and lodges in the then fashionable Egyptian Revival style, is in Stoke Newington High Street, but we took the less showy pedestrian entrance round the corner in Church Street, which was once the entrance to Abney House.

It was an appropriately damp and overcast day, and despite my husband’s cheerful talk of nesting warblers, the notices pointing out the numerous varieties of birds, trees and plants to be found in the park (including warnings about the fungi which contain arsenic, which the Victorians used to embalm bodies, and lead from the coffins), the runners with their headphones and the people walking briskly or throwing sticks for their excited dogs, I was overwhelmed, as always, by the palpable feeling of Victorian melancholy that hangs over the park. Death was ever-present for the Victorians and they certainly made the most of it – Queen Victoria, after all, spent most of her life in mourning after Albert’s death. Tennyson wrote one of his finest poems, In Memoriam, after the loss of his close friend Arthur Hallam who died at the age of 22 (see Christopher Rush’s piece in SF no. 63).

Memorials line every walk and fill every overgrown glade, many in various stages of decay, half collapsed and almost hidden by ivy – stone angels, pillars topped by draped funerary urns, heartrending small memorials to children. A slumbering marble lion marks the family grave of the lion tamer Frank Bostock who travelled the world with his extraordinary menagerie of animals during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Other well-known figures of the Victorian age including many dissenters and anti-slavery campaigners are buried here, and just inside the entrance is a massive version of a Salvation Army badge, a memorial to the army’s founders William and Catherine Booth who both confidently ‘went to heaven’ in 1912 and 1890 respectively. There was something oddly energizing about the sheer over-the-topness of it all, but I came away feeling rather subdued by all these memento mori, and was glad of a restorative coffee and a chocolate croissant from one of the smart coffee shops in Church Street, which are now tentatively opening their doors.

Photo: David Holt

From Gail, Manaton, 24 July 2020

Looking out of the window from my desk, it’s clear that we are in high summer. The trees on Lustleigh Cleave, which in spring run from the palest lime of the beech through endless shades of green to the dark moss of the Scots pines, are now a more uniform colour and heavy with leaf. The fields too have changed. The sheep have been hard at work ever since they arrived in March, but they won’t eat nettles, thistles or dock, nor will they touch grass if it has got beyond a certain height. So last week our friend Steve arrived on his small blue New Holland tractor to top the fields.

There’s something rather mesmerizing about watching a tractor at work. In some areas it’s plain sailing, and a pleasure to watch reeds and weeds disappear in a trice. In others it’s a much riskier operation. In amongst the grass lie half-submerged granite outcrops – things of beauty in the winter when they are covered in moss and sedums and lichen but ruinous to the blades of the topper. The occasional metallic screech brings Steve to a sudden halt. A quick inspection – no damage done this time, thank goodness ‒ and he’s back on the tractor seat and setting off for the next swathe. Now the fields look like a well-brushed carpet.

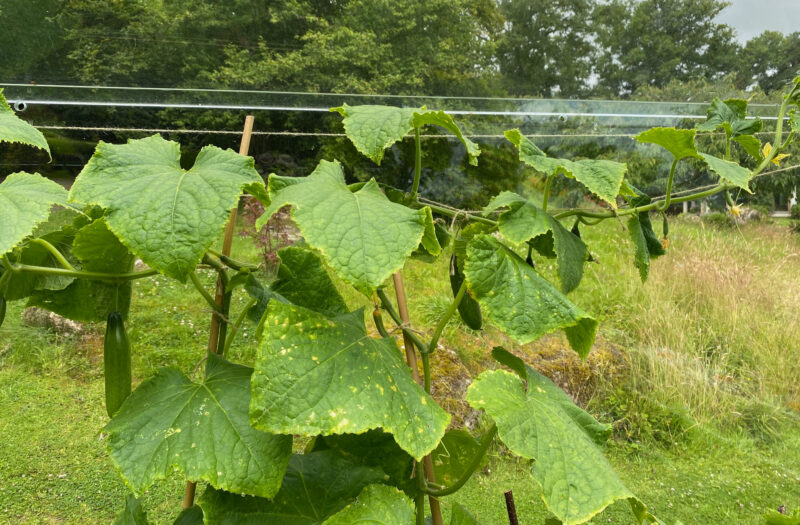

Up near the house I’ve been pottering in the greenhouse. To my amazement the aubergines have begun to fruit and there are now several hiding beneath the leaves and growing fatter every day. The cucumbers have reached the top of their canes and I’ve had to train them horizontally on twine – there’s nowhere else for them to go. The branches of the tomato plants are heavy with ripening fruit, and in several old galvanized washtubs sit great fat lettuces almost ready to be picked. Out among the raised beds the broad bean plants are threatening to collapse over their supports and the runner beans have reached the top of their tripods. It’s just as well, then, that with the easing of lockdown we’ve been able to have children and grandchildren to stay for a while. All those vegetables need eating.

We’ve had other visitors too. We bumped into Andrew, a keen local bird watcher, on an afternoon walk who said he’d seen a rare spotted fly catcher – a trans-Sahara migrant – in our garden, and down by the lake a cormorant and a little crested grebe, both unusual visitors for Manaton. And yesterday I found a toad, contentedly basking in the sun by the greenhouse. Perhaps she’s the toad who laid all that spawn that I mentioned in our first diary entry back in March.

Photo: Andrew Taylor

With all this activity in fields and garden, it’s been hard to concentrate on work, especially since Hazel and I are now trying to turn our thoughts to the winter issue and put ourselves in the right mood for a cosy, cheering, festive season which must be reflected in the articles we choose. So far we’ve picked articles on bell-ringing, George Eliot, Russian folk tales, the art of drinking, bibliomania, a London childhood, a couple of spine-chilling murders, some unputdownable thrillers and a beautifully written novel by William Trevor. But have we got the balance right? Only time and the first proof will tell.

Evocative as always and I have put Abney Park on my list for a future London visit.

Something struck me whilst reading your pieces. It is that neither of you use the semi-colon (apologies if I have missed any). My English teacher at Ipswich High School GPDST during the 60s was a stickler for grammar, but I scratch my head trying to remember anything she said concerning the use of the semi-colon. In my drafting days, I used it in lists of points. Otherwise, I have got along without it. Some Canadian-educated colleagues and friends use it liberally. Is this a North American vs UK English language phenomenon – or simply a matter of taste?

At school, in my teens, we were once asked to write an essay composed of as few sentences as possible, by using the semi-colon. I really enjoyed this and it has stayed with me. Many years later, I am still an enthusiast for the semi-colon!

I wouldn’t be without the semi-colon. It is useful as a longer pause than a comma.

As interesting as ever. I’d no idea how many parks exist around Highbury, let alone this monumental cemetery, dripping with Victorian atmosphere. I love the slumbering marble lion. And Gail, your burgeoning green houses almost convince me that ours is as productive. Time to remove those lower tomato leaves . . .

I really enjoyed your very atmospheric essay on Abney Park cemetery. It brought to mind the overgrown and eerie cemetery in George Town, Penang with its resplendent graves of Penang’s early European inhabitants, the cemetery in Moscow full of wonderful sculptures. Tombs provided an outlet for artists’ creativity during the dark years of cultural repression and the cemetery with its dark trees around the English church in Lisbon that always gave me like your writer, a fit of the glooms.

Utterly seduced by the diaries, as always, and fascinated by the comments about semi-colons. I was a pupil at the French Lycée in London in the late 50s, where we were taught strict punctuation rules. A semi-colon was for ‘marking a pause of average length’, as well as to separate parts of a sentence already subdivided by a comma. Perhaps most importantly, it was used to separate ‘extended propositions of the same nature’, as in ‘The duty of a leader is to command; that of a subordinate, to obey.’ So maybe it is related to nationality, as Sue Dawes suggests?

The semi-colon is a splendid institution: two (or more) statements link more closely to each other than either to surrounding statements; a comma will serve between list items, but can’t replace the semi-colon in even moderately formal language. I hope this comment might start another small loop of discussion on under-used punctuation marks.

I was interested to read opinions on the use of the semi-colon, which I never use; maybe an idle excuse for not pressing the ‘shift’ key IMHO. However, are others as devoted as I to the hardy colon? This is an example from correspondence yesterday.

“We have been watching a Netflix series that of course reminded us of all of your family: Marseille, starring the unique Gerard Depardieu, Benoit Magimel and the beautiful Geraldine Pailhas.”