Many young men feel trapped and unappreciated in uncongenial jobs, and on a hot summer day in 1871 one 22-year-old felt more frustrated than most.

Edmund Gosse, son of the famous naturalist Philip Henry Gosse, had worked at the British Museum since he was 17. His father’s friend Charles Kingsley had helped secure him the post of Junior Assistant in the Department of Printed Books. For someone with literary ambitions, this must have seemed an attractive position but it was, in fact, a clerical treadmill. With the other Juniors, his task was simply to write out the seemingly endless stream of revised entries prepared by his seniors for the catalogue of what was then the largest library in the world.

The sense of imprisonment was made worse by his working conditions. The Junior Assistants were confined in the south-west basement of the iron book-stacks that encircled Panizzi’s new Reading Room. Gosse later described it as ‘a singularly horrible underground cage, made of steel bars, called the Den’. The bars were to allow light to filter in since there was no artificial lighting. It was freezing in winter and stifling in summer. A number of deaths were attributed to it. The resulting scandal even reached the pages of The Times.

On this particular day, however, in these hot and gloomy surroundings heavy with the scent of rotting leather, Gosse’s labours were interrupted. One of the Senior Assistants, who had been keeping a friendly eye on him, descended literally from on high and appeared at his desk.

William Ralston was an imposing, almost patriarchal figure – six feet six inches tall, with a beard that reached to his waist. Though destined to come to a sad end, at this stage he was still a rising star, a distinguished Slavonic scholar, the friend and translator of Turgenev. He was also on familiar terms with many famous authors. He brought the exciting news that there was an important visitor upstairs in the Museum, one of the to

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inMany young men feel trapped and unappreciated in uncongenial jobs, and on a hot summer day in 1871 one 22-year-old felt more frustrated than most.

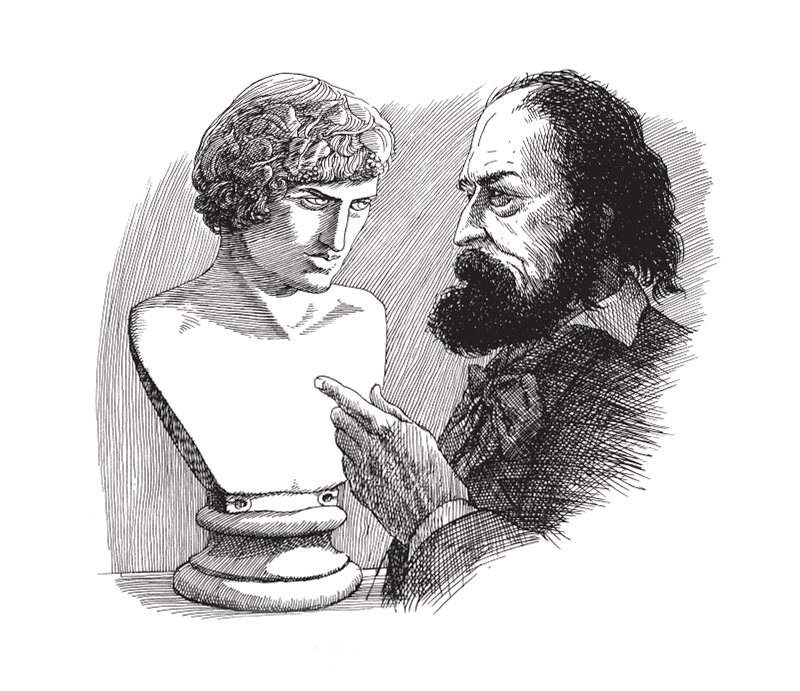

Edmund Gosse, son of the famous naturalist Philip Henry Gosse, had worked at the British Museum since he was 17. His father’s friend Charles Kingsley had helped secure him the post of Junior Assistant in the Department of Printed Books. For someone with literary ambitions, this must have seemed an attractive position but it was, in fact, a clerical treadmill. With the other Juniors, his task was simply to write out the seemingly endless stream of revised entries prepared by his seniors for the catalogue of what was then the largest library in the world. The sense of imprisonment was made worse by his working conditions. The Junior Assistants were confined in the south-west basement of the iron book-stacks that encircled Panizzi’s new Reading Room. Gosse later described it as ‘a singularly horrible underground cage, made of steel bars, called the Den’. The bars were to allow light to filter in since there was no artificial lighting. It was freezing in winter and stifling in summer. A number of deaths were attributed to it. The resulting scandal even reached the pages of The Times. On this particular day, however, in these hot and gloomy surroundings heavy with the scent of rotting leather, Gosse’s labours were interrupted. One of the Senior Assistants, who had been keeping a friendly eye on him, descended literally from on high and appeared at his desk. William Ralston was an imposing, almost patriarchal figure – six feet six inches tall, with a beard that reached to his waist. Though destined to come to a sad end, at this stage he was still a rising star, a distinguished Slavonic scholar, the friend and translator of Turgenev. He was also on familiar terms with many famous authors. He brought the exciting news that there was an important visitor upstairs in the Museum, one of the towering literary figures of the day, Alfred Tennyson. Ralston wanted to take Gosse upstairs and introduce him to the Poet Laureate. It was a singular honour but Ralston’s confidence in Gosse was not misplaced. Over the course of a literary life extending almost another sixty years, Gosse was to meet and befriend a multitude of authors and to describe many of them in his writings. Indeed, such was the position he came to exercise in the literary world that H. G. Wells famously characterized him as ‘the official British man of letters’. Before describing Gosse’s encounter with the author of In Memoriam and The Idylls of the King, it is worth reflecting on his later admission that the Victorians carried their admiration of individuals to too high a pitch: ‘they turned it from a virtue into a religion, and called it Hero Worship’. To do this we must move forward half a century towards the end of Gosse’s career. In 1918, he was to review one of the latest literary sensations of the age, Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians (see SF no. 33). He was well aware that this volume was but one manifestation of an intellectual revolution which had been rapidly gathering pace and which dismissed many aspects of Victorian art, literature and architecture as readily as ‘the glued chairs and glass bowls of wax flowers of sixty years ago’. To much of this movement Gosse was decidedly sympathetic, not least in the sphere of biography. His particular bête noir was the two-volume ‘Life and Letters’, whose pompous platitudes commemorated in print the recent dead. As it happens, a particularly egregious example of the form was the life of Tennyson himself written by the poet’s son, and Gosse made merciless fun of its preening pieties.Gosse spoke with feeling. Though he had himself produced an orthodox biography of his father, his most famous work, Father and Son, written at the prompting of George Moore, famously subverts the traditional form. The book is so well-known that it is easy to forget today how revolutionary this frank examination of his father’s religious faith and its unhappy effect on his only child actually was. In short, Gosse was a pioneer of candid autobiography. He had also had an unhappy experience when writing one of his later biographies. He hinted at this when he observed in 1912: ‘The great danger of twentieth-century biography is its unwillingness to accept any man’s character save at the valuation of his most cautious relatives, and in consequence to reduce all figures to the same smooth forms and the same mediocre proportions.’ As prophecy, this was to be wide of the mark, but it accurately sums up his own recent tribulations. In his opinion, of all his friends the most remarkable had been Algernon Charles Swinburne, a writer he was convinced would take his place as ‘one of the few unchallenged Immortals’. Gosse determined that he should portray him for posterity. Unfortunately, when Swinburne died his closest surviving relatives were two elderly ladies, his sister Isabella and his cousin and former sweetheart Mary Disney Leith. These stoutly maintained that Swinburne did not drink (he was an alcoholic), was a practising member of the Church of England (he was an atheist) and would never have spoken to a woman like the equestrian artiste Adah Isaacs Menken (she was briefly his mistress). So as not to cause them distress, Gosse felt bound to respect their wishes. The subject of flagellation was not even raised. For Gosse himself some forms of truth were unacceptable. However, these facts were widely known. In consequence, Gosse’s biography was ill received. With all this in mind we can now return to that hot summer day fifty years earlier when in Ralston’s wake Gosse scurried up the spiral metal staircase from the Museum basement for his introduction to the literary colossus of the age. Gosse described his meeting with Tennyson as taking place in ‘the long First Sculpture Gallery’. This was, in fact, the gallery at the south of the Museum which runs west from the Front Hall towards the Assyrian and Egyptian Galleries. Latterly it has been given over to postcards and left luggage but at this period it was the Roman Gallery and we need to imagine it as it was in its prime. On one side, beneath the windows looking out on Smirke’s Grecian colonnade, were Roman antiquities discovered in Britain; on the other Roman mosaics were affixed to the walls and beneath them were rows of statues and busts of Roman rulers from Julius Caesar to Gordian I. In the centre of the gallery stood the striking if heavily restored marble equestrian statue of a naked young Julio-Claudian prince, then thought to be Caligula. There among the sculptures was Tennyson with his close friend James Spedding, the editor and biographer of Sir Francis Bacon. Looking back, Gosse clearly retained the sense of awe he felt on that day. ‘Tennyson was scarcely a human being to us, he was the God of the Golden Bow.’ In his mind’s eye, Tennyson stood there among the Roman emperors as if he were one of them. With exquisite tact, Ralston engaged Spedding in conversation so that Gosse could have the great poet to himself. Gosse’s own first volume of poems had been published the year before. It had sold twelve copies. Tennyson seemed aware of it and was ‘vaguely gracious’ about Gosse’s verse. Ralston had told Tennyson that Gosse was about to visit Norway. Tennyson described his own visit. The young man was totally overcome in the presence of his hero. He could scarcely utter a word. What could have been an embarrassing silence was interrupted by someone suggesting that they look at the sculptures. In retrospect, what struck Gosse was how swarthy Tennyson was. He thought that his friend Hamo Thornycroft had caught the essence of him in the statue later erected at Trinity College, Cambridge, but only if the lightness of the stone were converted into dark. This transposition may have influenced his memories of the occasion for he extended it from its subject to his surroundings. He described Tennyson stopping in front of ‘the famous black bust of Antinous’. In fact, Hadrian’s favourite, portrayed with the attributes of Bacchus and, in the words of a later curator, displaying ‘a sullen and sensual expression’, is fashioned out of white Parian marble. The Laureate remarked ‘Ah! this is the inscrutable Bithynian,’ before adding himself, equally inscrutably, ‘If we knew what he knew, we should understand the ancient world.’ When Gosse came to describe this episode in his essay ‘A First Sight’, published in 1912, he did not disguise that what he felt for Tennyson was hero-worship, though he doubted if such a feeling were any longer possible: ‘no person living now calls forth that kind of devotion’. The familiarity occasioned by cheap newspapers and abundant photographs had dispersed the aura of sanctity and romance that surrounded popular idols. He did not guess that precisely this proliferation of information would feed other forms of celebrity. He also did himself a serious injustice. His feelings, as he describes them, were far from ridiculous and he portrayed them with touching sensitivity, vividly recapturing the experiences of youth. Gosse understood that the vital thing for any biographer is not to like or approve of their subject but to try to understand them. For this, you need ‘sympathetic imagination’. It was a quality his own parents had lacked with such disastrous results for his childhood, and it was just such a lack, for all his admiration of his ‘pellucid stream of prose’, that he detected in Lytton Strachey. In consequence, Strachey’s characters were not living people but amusing puppets. By contrast, what Gosse sought to convey in his pen portraits was reality. In this sense, he was more modern than Strachey. He was striving for a world in which representations of Tennyson and Antinous were neither white nor black, because people are more complicated than that and everyone, without exception, is a shade of grey.Thus the priesthood circled round their idol, waving their censers and shouting their hymns of praise, while their ample draperies effectively hid from the public eye the object which was really in the centre of their throng . . . Their fault lay not in their praise, which was much of it deserved, but in their deliberate attempt in the interests of what was Nice and Proper – gods of the Victorian Age – to conceal what any conventional person might think not quite becoming. There were to be no shadows in the picture, no stains or rugosities on the smooth bust of rosy wax.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 35 © C. J. Wright 2012

About the contributor

C. J. Wright was Keeper of Manuscripts at the British Library until his retirement in 2005.