It is a wolfish face. The eyes of the man in the photograph peer over a long, grizzled beard and glitter. They speak not of cruelty or pre-dation but of mischief. They are a little wary, and a little weary. The smile suggests that this man has something to say and is deciding how much you can handle. It is the face of a man who has seen his fellow men, and seen them whole; who is not overly pleased with what he sees. It is the face of a congenital contrarian. This man enjoys lighting fires under people just to watch them jump. I like him instantly, and would like to know him better, but his photograph sits atop an obituary. It is March 1989. Edward Abbey is dead.

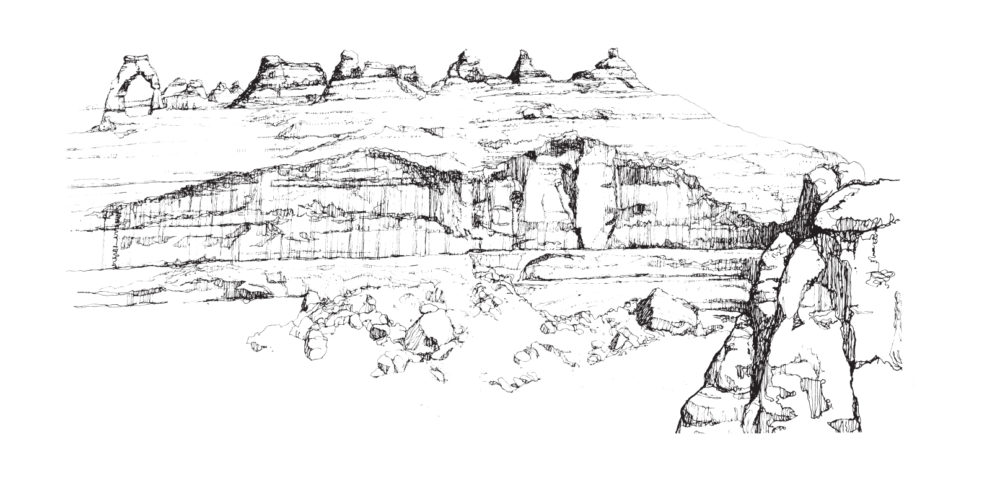

Abbey was born in 1927 on a family farm in the mountains of Appalachia, in western Pennsylvania, but before he was 20 he had travelled to the American south-west and fallen in love with the ‘implacable indifference’ of the red rock desert and labyrinthine canyons of ‘the four corners’, the point at which Utah, Arizona, New Mexico and Colorado converge. It would forever speak to his heart. By the 1950s he was working as a park ranger, and in 1956 he began two seasons at the Arches National Monument in south-east Utah, now a national park. He was home. It was a time of ‘pure, smug, animal satisfaction’. He began to keep a journal that would later blossom into an elegiac memoir: Desert Solitaire (1968).

Abbey’s memoir begins with his arrival at the Arches in early spring. With the full weight and authority of the US National Park Service behind him, an official though battered pickup truck, and his very own house trailer awaiting him, all he has to do to set up home is fish a dead rat out of the toilet, sweep up the mouse droppings, adopt a gopher snake to drive away the rattlesnakes

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inIt is a wolfish face. The eyes of the man in the photograph peer over a long, grizzled beard and glitter. They speak not of cruelty or pre-dation but of mischief. They are a little wary, and a little weary. The smile suggests that this man has something to say and is deciding how much you can handle. It is the face of a man who has seen his fellow men, and seen them whole; who is not overly pleased with what he sees. It is the face of a congenital contrarian. This man enjoys lighting fires under people just to watch them jump. I like him instantly, and would like to know him better, but his photograph sits atop an obituary. It is March 1989. Edward Abbey is dead.

Abbey was born in 1927 on a family farm in the mountains of Appalachia, in western Pennsylvania, but before he was 20 he had travelled to the American south-west and fallen in love with the ‘implacable indifference’ of the red rock desert and labyrinthine canyons of ‘the four corners’, the point at which Utah, Arizona, New Mexico and Colorado converge. It would forever speak to his heart. By the 1950s he was working as a park ranger, and in 1956 he began two seasons at the Arches National Monument in south-east Utah, now a national park. He was home. It was a time of ‘pure, smug, animal satisfaction’. He began to keep a journal that would later blossom into an elegiac memoir: Desert Solitaire (1968).

Abbey’s memoir begins with his arrival at the Arches in early spring. With the full weight and authority of the US National Park Service behind him, an official though battered pickup truck, and his very own house trailer awaiting him, all he has to do to set up home is fish a dead rat out of the toilet, sweep up the mouse droppings, adopt a gopher snake to drive away the rattlesnakes (they like the mice) and beware of the cone-nosed kissing bug, whose bite seldom causes convulsions in healthy adults. By Charles Doughty or Wilfred Thesiger standards, Abbey the Desert Dweller is almost effete, a thought which would have elicited his complete agreement, but he’s equally good company. Unlike those more famously intrepid desert travellers, Ranger Abbey must soon confront that most pestilential of all pests, ‘sealed in their metallic shells like molluscs on wheels’, the Great North America Tourist, a creature which would have made both Thesiger and Doughty take to their heels.

But on his first day, far beyond the end of paved roads and 20 miles from another human being, Abbey is alone in 33,000 acres of incomparably austere beauty: arches and flying buttresses and teacup handles of sandstone, some the size of a man, some taller and wider than the nave of St Paul’s, in endlessly changing shades of deep rust and soft pink, rose and dusky violet. They have been carved not by the ceaseless wind but by water and ice. The same abrasion has created canyons so deep that dropping a stone over the edge Abbey can light his pipe before he hears the sound of the impact below. The vistas are vast, and the theatre of lightning and the sweeping purple curtains of rain can be enjoyed in complete silence as they approach, the clash of thunder too far away to be audible. When the storms do arrive, their violence will break the arid desert air like gunfire.

Time at the Arches is measured not in years but in geological epochs. There is a sense of permanence, but even on his first morning Abbey knows this is an illusion. One day the unpaved roads will be suffocated in asphalt, the park will boast flush toilets and vending machines, and the Arches will be ‘managed’ and ‘improved’. He is immediately consumed with the protective, greedy possessiveness that will be one of the hallmarks of his journal. Even before the tale of his official duties has begun there are echoes of Thoreau. He is there ‘not only to evade for a while the clamour and filth and confusion of the cultural apparatus but also to confront, immediately and directly if it’s possible, the bare bones of existence, the elemental and the fundamental, the bedrock’.

The Arches would in many travellers provoke metaphysical speculation, but for Abbey, who read philosophy at university, there is only the hard reality of rock, and beneath that, more rock. Like Dr Johnson kicking a large stone to refute the metaphysician who doubted the physical universe, Abbey has no time for the metaphysical idealist. He recommends throwing a rock at his head if you meet one; if he ducks, you’ve met a liar. Abbey is too busy imbibing the world around him to have much time for metaphysics. A ‘next’ world? He has yet to meet anyone who is worthy of this one.

Abbey likes to stir things up. He’s good at being angry – most of us develop a talent for things we enjoy – and he can be as unforgiving as the heat from the desert sun in August or the arid cold of January nights. He knows that any writer who is willing to call things by their rightful names will not be welcome for long. As a man who loves the desert as deeply as he hates the human greed and folly that threaten to destroy it, he has lots to be angry about. He does not go gentle into that good desert, but rages, rages. He is particularly vociferous in his reaction to the Glen Canyon Dam. A gift of the US Bureau of Reclamation, it turned Glen Canyon, one of the most beautiful places on earth, into a stagnant algae-laden silt trap now used to generate electricity, thus further ‘opening up the West’ to exploitation. To this day land developers, bankers and building contractors are putting homes for millions on land suitable only for the support of thousands, setting off yet more squabbles about water rights. The mighty Colorado River no longer reaches the Gulf of California in Mexico. It dwindles into a marsh. Almost every living thing in Abbey country stings, stabs, stinks or sticks – just like Abbey at his volatile best. The world needs people like him. In human affairs, the moderates are the ones who get things done, but it’s the radical fringe who ignite the spark that gets the engine turning. Abbey has often been described as a curmudgeon, which he considered, of course, high praise. In his dictionary a curmudgeon is someone whoUnder the desert sun, in that dogmatic clarity, the fables of theology and classical philosophy dissolve like mist. The air is clean, the rock cuts cruelly into flesh; shatter the rock and the odour of flint rises to your nostrils, bitter and sharp. Whirlwinds dance across the salt flats, a pillar of dust by day; the thornbush breaks into flame at night. What does it mean? It means nothing. It is as it is and has no need for meaning.

He believed that an artist has two chief responsibilities: art and sedition. He was a man who lived his beliefs, and lived them well. According to documents released through the Freedom of Information Act, Abbey’s FBI file totals 148 pages, the names of the cowards and government toadies who furnished the information conveniently blacked out. This file is for a man whose only crime was to question the wisdom of his government. One wonders how big the files for Mark Twain and Henry Thoreau might have been. Abbey’s voice is vigorous and strong. Like every contrarian from Dr Johnson to George Bernard Shaw he sometimes voices opinions merely to savour their impact, but there is no prevarication, no equivocation, no nonsense. There is no base alloy in Edward Abbey. He is pure, cold, glittering steel. He says what he thinks and means what he says, holds strong and often unconventional opinions, and would be alarmed if one day he found himself in step with the majority. Anyone who describes Henry James as ‘our finest lady novelist’ is not out to make friends. Abbey claimed to have kept his .357 magnum revolver on his desk when he wrote. No wonder. Desert Solitaire is not, however, all curmudgeonly mirth and merriment. There are thought-provoking digressions on the meaning of civilization, the limits of machines, silence, human vanity, the neuroses of ants, the alchemy of petrified wood, and the sinister glamour of quicksand, as well as grimly explicit instructions on how to feed a flock of hungry vultures by dying of dehydration. Abbey the Barbarian is (mostly) a façade; he just enjoys himself hugely acting like one. He loves Thoreau, J. S. Bach, Montaigne, Sam Johnson and Bertrand Russell (nobody’s perfect), and along the way quotes Pablo Neruda, Shakespeare, Sir Walter Raleigh and Robinson Jeffers. How much of a barbarian could a man be if he is reminded of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony while herding cows? Abbey can also evoke a quiet serenity, watching the ‘blue scarves of snow flying in the wind’, the evaporation of rain ‘dangling out of reach in the sky’, clouds ‘unfurling and smoking billows in malignant violet, dense as wool’. He hears music in the names of desert flowers: Indian paintbrush, skyrocket gilia, locoweed, globemallow, cliffrose. Even flash floods, ‘thick as gravy . . . lathered with scuds of bloody froth’, surprise and delight. And who could resist a trip to Wolf Hole, Tukuhnikivatz, Dead Horse Mesa or The Maze? Edward Abbey will take you there. He is a man with sharp corners, rough-grained, occasionally foolish, and with an earthy sense of humour; but he is a hard man not to like. On his death, a few close friends gathered to celebrate his life with a generous supply of cold beer, whiskey, steak and corn-on-the-cob, just as he’d instructed. Then they placed their unembalmed friend in a Chevy pickup truck, wrapped in his old blue sleeping-bag, and went for a ride, which is quite legal. Fulfilling Abbey’s last wish in a final delicious act of anarchism, they drove far out into the Cabeza Prieta Wilderness and buried him, which is quite illegal. He could not have had a more fitting send-off or a more appropriate restingplace. It is said that nothing in the desert can be buried out of reach of a hungry coyote. Being both the guest of honour and the main course at a coyote banquet would have pleased him enormously, and provoked his finest wolfish grin.hates hypocrisy, cant, shame, dogmatic theologies, the pretences and evasions of euphemism, and has the nerve to point out unpleasant facts and takes the trouble to impale these sins on the skewer of humour and roast them over fires of empiric fact, common sense, and native intelligence.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 30 © Richard Platt 2011

About the contributor

Though he holds strong and often unconventional opinions, and is known to call things by their rightful names, Richard Platt does not write with a gun on his desk, but with an imperious and ever-vigilant parrot on his shoulder.