I enjoy reading thrillers. I might like to claim that literary fiction is my constant companion, but for most of the time it isn’t – the novels that Graham Greene described as his ‘entertainments’ give me far greater pleasure than his more serious books. Similarly, when my work as a historian took me to the period between the First and Second World Wars I found that Eric Ambler’s thrillers, written at the time, effectively captured the contemporary atmosphere, just as do Alan Furst’s more recent books. Both explore the impact of the interwar struggle between fascism, communism and democracy on innocent individuals, men who find their lives tossed about on the great waves of history. But always men. What about the women?

One of the books I read when beginning my own work on that period was Europe of the Dictators by Elizabeth Wiskemann, from which it was clear that her historical writing was informed by her own past. I wanted to know more, so I tracked down her autobiography, The Europe I Saw (1968). I was captivated. Here was a woman whose adventures in real life might have formed a model for the fictions of Greene, Ambler or Furst. But she was more than one of the little people whose fate was determined by big events and powerful people; she met many of the powerful, and she played her part in the big events.

The Europe I Saw is not a conventional autobiography, although from its first few pages we learn that Elizabeth Wiskemann was born in 1899, the youngest child of a mother with Welsh and Huguenot roots and a German father who had moved to London as a young man. She went to Newnham College, Cambridge, where she took a first-class degree in history in 1921. Several difficult and poverty-stricken years followed before she became a history tutor at Newnham, where she worked on her doctoral thesis.

For some reason she had attracted the enmity of her senior examiner, and her thesis on Napoleon III and the Roman Q

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign in orI enjoy reading thrillers. I might like to claim that literary fiction is my constant companion, but for most of the time it isn’t – the novels that Graham Greene described as his ‘entertainments’ give me far greater pleasure than his more serious books. Similarly, when my work as a historian took me to the period between the First and Second World Wars I found that Eric Ambler’s thrillers, written at the time, effectively captured the contemporary atmosphere, just as do Alan Furst’s more recent books. Both explore the impact of the interwar struggle between fascism, communism and democracy on innocent individuals, men who find their lives tossed about on the great waves of history. But always men. What about the women?

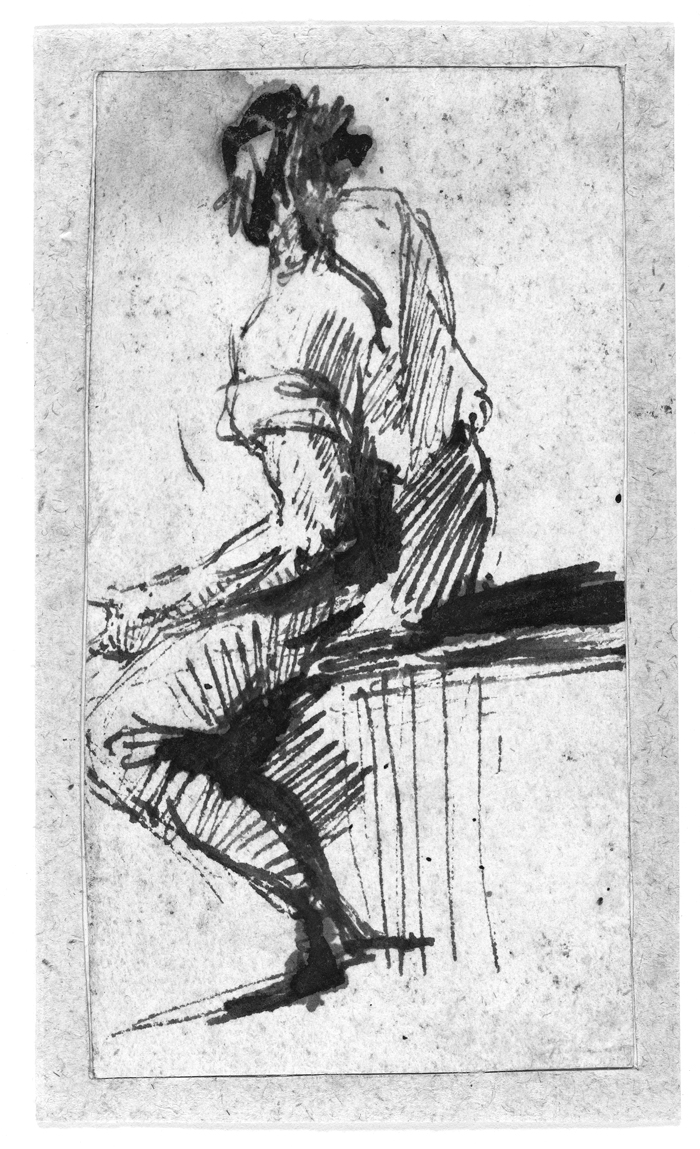

One of the books I read when beginning my own work on that period was Europe of the Dictators by Elizabeth Wiskemann, from which it was clear that her historical writing was informed by her own past. I wanted to know more, so I tracked down her autobiography, The Europe I Saw (1968). I was captivated. Here was a woman whose adventures in real life might have formed a model for the fictions of Greene, Ambler or Furst. But she was more than one of the little people whose fate was determined by big events and powerful people; she met many of the powerful, and she played her part in the big events. The Europe I Saw is not a conventional autobiography, although from its first few pages we learn that Elizabeth Wiskemann was born in 1899, the youngest child of a mother with Welsh and Huguenot roots and a German father who had moved to London as a young man. She went to Newnham College, Cambridge, where she took a first-class degree in history in 1921. Several difficult and poverty-stricken years followed before she became a history tutor at Newnham, where she worked on her doctoral thesis. For some reason she had attracted the enmity of her senior examiner, and her thesis on Napoleon III and the Roman Question was only awarded an M.Litt. As a result she left Cambridge and went to Berlin in the autumn of 1930: ‘If I had remained an academic specializing in the nineteenth century, I suppose my life would have been considerably duller than it became.’ After this introduction, the first half of the book is divided into chapters on each of the countries of central Europe during the ferment of the 1930s, as seen by a working journalist with the mind of a historian and a well-stocked address book. Following her initial visit to Germany in the last years of the Weimar Republic she returned to Cambridge and by 1932 she had settled into a rhythm, ‘teaching in Cambridge during the University term and spending a maximum vacation period in Germany or some area related to it in order to describe what was happening there’. Her first article was sold to the New Statesman in April 1932, and thereafter she found that by writing four articles after each journey she could fund another few weeks abroad providing she lived frugally. She became a regular visitor to Germany, and also Austria, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Hungary, Romania and Poland. She had a talent for making contacts, not only in politics and journalism but also in the arts. She saw the original production of Brecht’s Threepenny Opera, danced with the caricaturist and satirist George Grosz, spent an evening in a Vienna café with the philosopher György Lukács and the writer Robert Musil, and took tea with Thomas Mann and his family. The first two chapters of the book, on Germany, vividly evoke the atmosphere of the time. Attending her first Nazi rally, she was filled with foreboding, and she subsequently witnessed Nazi violence at first hand. By 1933, when she returned to Berlin a few days after Hitler became Chancellor, she had acquired the habit of not mentioning names on the telephone or writing them in full in her diary. Her articles increasingly drew attention to the dangers of Nazism, and on 17 February 1936 the police in Munich, having taken exception to one of them, issued instructions that her arrival in Germany be officially reported. When she returned to Berlin in July she was arrested and taken to the Gestapo’s headquarters on Prinz Albrechtstrasse. There she was interrogated, rather ineffectively, about her articles, while British Embassy staff, alerted by Norman Ebbut, the Times correspondent whom she had been visiting when arrested, attempted to have her released. Her interrogator, ‘the blond beast type’ in full SS uniform, wanted her to admit to having written anti-German statements. Could she have stated that Jews were maltreated? ‘I said why yes, it’s true, isn’t it?’ After three hours she was told that if she signed a statement that she could have written such material, and in view of the forthcoming Olympic Games, she would be released. She signed, returned to Ebbut’s flat, ‘drank six strong drinks straight off’ with no noticeable effect, and left the country the following day. She could no longer return to Germany, but, as the following chapters reveal, she could still follow the impact of Nazi policy by visiting other countries in central Europe, and her talent for making contacts gave her access to some of the most prominent political figures of the time. For example, thanks to having met his son at a lunch in London, the first person she interviewed in Prague was Tómaš Masaryk, the President of Czechoslovakia. In Vienna, she spoke to Hitler’s special envoy to Austria, Franz von Papen, the former German Chancellor; in Budapest to István Bethlen after he had ceased to be Prime Minister; in Romania to the leader of the Peasant Party; and in Warsaw to General Sikorski, future leader of the Polish government-in-exile. She also knew journalists from all over Europe. By 1939 she had written one book on the relationship between the Czechs and the Germans and another, on Europe post-Munich, which appeared in November 1939, inopportunely entitled Undeclared War. By then she had decided that her most useful wartime role would be to work for the Foreign Office in Switzerland, where she had numerous foreign contacts. After an interview with a top security official, who told her that she was ‘not nearly such a fool as he had expected a woman would be’, she went to Zurich in January 1940. Part of her job, after Dunkirk, was to monitor the output of the German press, an operation which hitherto had been carried out in the Low Countries. She was also responsible for reporting on Stimmung, ‘the German state of mind and everything contributing to it’. This required her to build contacts with anyone who had access to the country: Swiss Berlin correspondents visiting home, Swiss businessmen visiting Germany, and Germans visiting Switzerland. She was one of the few British diplomats who was allowed to meet enemy subjects, so she cultivated as many as she could find, from businessmen and theatrical people to Adam von Trott, the diplomat who was later hanged for plotting against Hitler. Her account of him demonstrates the strain that must have attended her daily life during the war:He caused me great anxiety. With his striking appearance – that immensely high forehead – he was someone you could not miss, and in those days only Poles or Germans were called Adam. So when he rang me up and said in his nearly perfect English ‘It’s Adam speaking’ anyone listening in could be in no doubt that it was Adam von Trott zu Solz. I begged him to call himself Tom, Dick, or Harry – I was so trained to recognize voices by then that this would have caused me no difficulty. Yet he never could bring himself to take this simple precaution. He was a bewilderingly brilliant creature, infinitely German in the intellectual complexity in which he loved to indulge . . . [He] had a brother fighting in Russia and I tried to get him to tell me about Stimmung on the Ostfront; I seldom got anything but his own political theories.I began to wonder if there was any supporting evidence for her stories. When I was working in the National Archives at Kew I typed ‘Berne Legation’, where she was based from 1940, into the online catalogue. I was rewarded by two fat Foreign Office files of intelligence reports. They demonstrated the variety of information she gathered: on food rationing in France, the impact of air raids, student riots in Munich, criticism of BBC broadcasts to the occupied countries, a warning of the forthcoming German attack on Yugoslavia in 1941, and rumours of a shortage of raw materials in Germany in 1942. They were mostly in typescript, but there were a few pages in her handwriting. When you have become fascinated by the life of a person you will never meet, holding a report actually written by them produces a wonderful sense of contact. And these files contained, in effect, the raw material for the second half of The Europe I Saw, so reading them was like peering over the author’s shoulder as she wrote. They show that she was not a spy in the sense that she operated under cover in enemy territory, but she was certainly a collector of intelligence, and she had to be careful about the security of her material and not draw attention to those she met. As she tells us, among them were several art dealers, who were invaluable because, like actors, they had international connections. They included the Wertheimers, husband and wife, German Jews who had escaped to Paris and then from Vichy France to Basle. They gave her a drawing by Piranesi, ‘as a prize for helping the Jews’, they said. She valued it above any wartime decoration: ‘It is the focus of my sitting-room today and is destined for the Fitzwilliam museum.’ What happened to it, I wondered? I went to the online catalogue. Object number PD.44-1971 in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge is a small drawing of a seated figure, in brown ink on paper, and measuring about five inches by two and a half, by the Italian eighteenth-century architect and artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi. The accompanying note on its provenance states that it was ‘Presented to Miss Elizabeth Wiskemann by representatives of the art trade in gratitude for her courageous and tireless efforts on behalf of refugees during World War II’. Elizabeth Wiskemann continued to work as a journalist and writer after the war, but increasingly she returned to her original career as an academic historian, with teaching posts at Edinburgh and Sussex, and several important books to her name. She was, according to those who knew her, a small vivacious woman of great charm and independence. Sadly, by the early 1970s her eyesight was failing. Rather than face a future in which she would be unable to read, in July 1971 she took her own life. It was a life that in the 1930s and ’40s might have sprung from the imagination of a thriller writer, but for which we have the written evidence that it actually happened.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 65 © Paul Brassley 2020

About the contributor

Paul Brassley lives on Dartmoor, and although no longer paid to do so, continues to work as a historian.