Eric Linklater was a bit of a force of nature. He was born in Wales, but wished he hadn’t been, so he conjured an Orkney childhood and let everyone assume he had been born there. His father was Orcadian, a master mariner. Perhaps he was honouring that, and the longing his Swedish mother felt for the place. But he was 70 before he admitted his Welsh beginnings.

He was convinced he was ugly, a weakling – so he became a soldier and wrote the definitive war autobiography, Fanfare for a Tin Hat. He escaped death by a whisker, thanks to said tin hat, which he kept on his desk as a memento mori.

His love affair with Orkney was long and complex. Yet he only actually lived there for thirteen years, and he spent most of that time abroad. He built a fine house, and made up an Orcadian-sounding name for it – Merkister. There he fished, shot, ate, drank, loved, wrote. It was, in many ways, his anchor.

It’s now a fishing hotel, hung with stuffed glassy-eyed behemoths and delicate bright flies with exotic names – Erland’s cat, Norsky lad, glister cormorant. There’s a plaque depicting his rather crusty domed countenance; he’s described as ‘writer, historian, angler’, which he’d have approved of.

He was an insecure, prickly sort of man, prone to roaring when thwarted, attacked by skin eruptions and stomach upsets. He behaved magnificently badly, then apologized equally magnificently. His children became accustomed to domestic explosions during which fruit and crockery were thrown in all directions, and his wife Marjorie gave as good as she got. He wrote too much because he needed money – over twenty novels, three volumes of autobiography, five children’s stories, ten plays, dozens of essays, histories and jobbing introductions. How could his output not be patchy? They’re in every second-hand bookshop, those novels

And yet. There’s another man under all the bluster. A hopeless romantic. An elegant stylist. A writer not so m

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inEric Linklater was a bit of a force of nature. He was born in Wales, but wished he hadn’t been, so he conjured an Orkney childhood and let everyone assume he had been born there. His father was Orcadian, a master mariner. Perhaps he was honouring that, and the longing his Swedish mother felt for the place. But he was 70 before he admitted his Welsh beginnings.

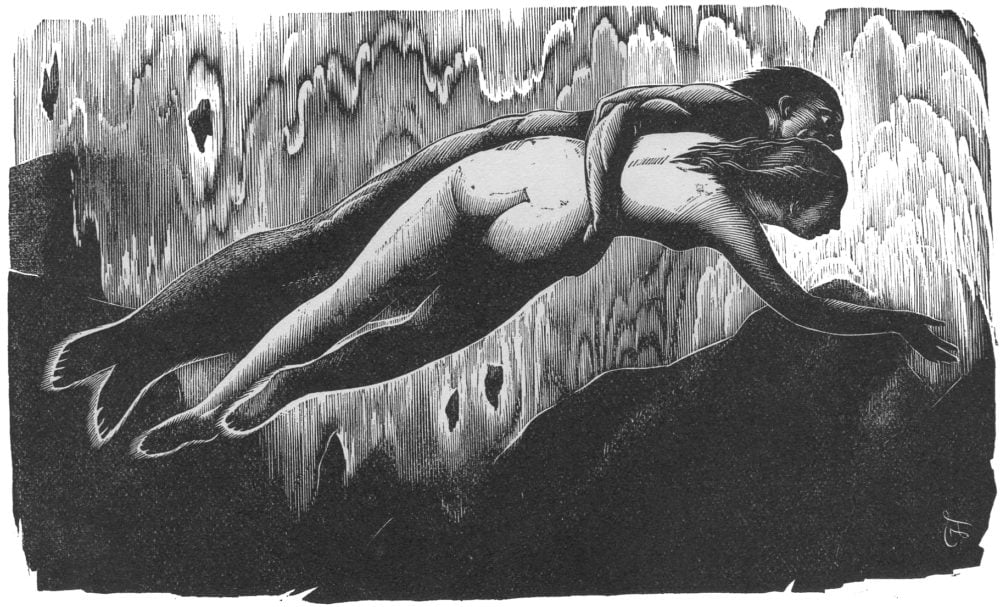

He was convinced he was ugly, a weakling – so he became a soldier and wrote the definitive war autobiography, Fanfare for a Tin Hat. He escaped death by a whisker, thanks to said tin hat, which he kept on his desk as a memento mori. His love affair with Orkney was long and complex. Yet he only actually lived there for thirteen years, and he spent most of that time abroad. He built a fine house, and made up an Orcadian-sounding name for it – Merkister. There he fished, shot, ate, drank, loved, wrote. It was, in many ways, his anchor. It’s now a fishing hotel, hung with stuffed glassy-eyed behemoths and delicate bright flies with exotic names – Erland’s cat, Norsky lad, glister cormorant. There’s a plaque depicting his rather crusty domed countenance; he’s described as ‘writer, historian, angler’, which he’d have approved of. He was an insecure, prickly sort of man, prone to roaring when thwarted, attacked by skin eruptions and stomach upsets. He behaved magnificently badly, then apologized equally magnificently. His children became accustomed to domestic explosions during which fruit and crockery were thrown in all directions, and his wife Marjorie gave as good as she got. He wrote too much because he needed money – over twenty novels, three volumes of autobiography, five children’s stories, ten plays, dozens of essays, histories and jobbing introductions. How could his output not be patchy? They’re in every second-hand bookshop, those novels And yet. There’s another man under all the bluster. A hopeless romantic. An elegant stylist. A writer not so much overlooked as swamped by the torrent of words that flowed from his Parker pen. The Sealskin Trousers collection of stories appeared in 1947. Our copy had a beautiful dust-jacket. It was bound in high-quality prewar cloth and, crucially for a young person reading beyond her understanding, had glorious wood engravings by Joan Hassall. All the tales in this slim book grabbed me in different ways – there’s a malevolent goose-girl, a magical illicit taxi ride across Edinburgh, an encounter with Swedish poets, for example – but it was the title story that really drew me. The inspiration, of course, is the selkie myth, which most Orcadians learn with their mother’s milk. You’ll maybe be familiar with the lament:I am a man upon the land I am a selkie in the sea And when I am far and far frae land My hame it is on Suleskerry.Seals have uncannily human, liquid eyes. They will observe you, from a sea-safe distance. They will follow if you sing to them. They seem to want your company, to be thinking about swapping their chilly habitation for something closer to the fire. It’s no surprise my Orkney ancestors told tales about them. As is often the case in myth, it’s all about transformations. Traditionally, grey seals could assume human form. Some said it only happened at Midsummer, the magical time, when we have no darkness on the island. But they had to divest themselves of their skins in order to enjoy legs, to dance all the light night away. If a lonely crofter snatched the skin of a beautiful selkie lass and hid it, she would be bound to him. The thief paid a price for his prize, though. His selkie wife might have webbed fingers or horny hard heels; she might wander the shoreline, keening, and show no bent for housework. The minute she found her skin, she’d be off to her watery home without a backward glance. These selkie tales are odd. The other mythical beings in Orkney (Finn folk, trows, giants, witches) had magical powers. They could be malevolent. Not so the selkies. They simply became people for a while – handsome, but otherworldly. Psychologists might now say it was the islander’s explanation for ‘unkan folk’ – those less practical souls who don’t quite fit into the community. Perhaps it’s about unhappy marriages. It’s not the worst way to explain a misaligned union, to say, clearly you’re a fish and I’m a fowl. But when I first read Linklater’s Sealskin Trousers, I didn’t yet know the myth. The title page of our edition bore an engraving of a lobster, claws tied ready for the pot, lying on a bed of seaweed. I did know about lobsters, the rich dark blue of them and their fan tails. Fishermen friends would come by with a couple. The lobsters clambered up the sink, then knocked the pot gently as they boiled to death. I had no idea you could make them beautiful, even the string on their claws, in a printed book. On the very next page was an unsettling engraving. It was my coastline, but a couple were heading into the sea, twined tightly together. He had impossibly muscular arms. They were moving so fast their hair was swept back. And of course they were naked. She had a beautiful ample bottom like an Ingres. I was probably a bit embarrassed to see how close they were to each other. He was very hairy and there was something funny about his feet. But her arm looked happy, as if welcoming the cold splash that was coming. The engraving on the opposite page was in total contrast. It was a banner bearing two seals smiling at each other. The lady seal had a shell necklace. The seaweed behind them was as intricate as a Renaissance tapestry. It felt domestic. Clearly, it was a happy ending, a celebration of a marriage. I suspect now that the book was in our house not so much because of the stories – my socialist father rather suspected what he saw as Linklater’s county pretensions and his ardent Scottish Nationalist sentiments – but because of Joan Hassall. She was one of a remarkable group of engravers, working in the 1930s and ’40s, who reacted against the commercialism of mass-produced illustration. They wanted to get closer to William Morris’s vision of the journeyman maker who gets his hands dirty, chooses his burins and boxwoods with care, pays close attention to nature. The variety of their work is remarkable, and rare, for often they used small presses and limited editions. In our multicoloured world, the economy of their line and the effort expended are irresistible. Their work reflected tumultuous decades – the tension of the 1930s, the pain of war, the relief and promise of peace. They’re also, just, well, stylish in the way that my mum’s tailored suits were – elegant down to the last dart. Hassall was born in Notting Hill, in 1906, the daughter of the man who brought us the poster ‘Skegness is SO bracing’. By the 1940s she was already highly regarded. In the odd way life has, war brought her good fortune. She was asked to replace the tutor of illustration at Edinburgh College of Art while he was away on war duties. It wasn’t an easy time for a Southerner. Hugh MacDiarmid and others were hot on the campaign for a distinctive Scottish art, and there was some anti-English sentiment about. But one of her allies was another Orkney son, the artist Stanley Cursiter, Director of the National Gallery of Scotland and a fine draughtsman in his own right. He was also Linklater’s pal. Hassall wasn’t happy as a teacher and she left Scotland to set up her own imprint, but she’d been seduced by the culture of the pro-independence lobby. She observed, ‘It seemed, even to my pro- English eye, that Scotland had not been fairly treated, and it made me ashamed.’ Given the small Edinburgh arts world, it’s not surprising she was asked to work on these stories – and illustrated them in a year when she also designed editions of Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses and Burns’s poems, and another in a series of chapbooks for the Scottish Saltire Society. But her image of the descending couple, the one which unsettled me so much, is considered to be one of her best. The book was first published in a limited edition of fifty. Linklater, after a liquid lunch, signed twenty and then said he’d had enough and would sign the rest J. B. Priestley. This may not be true; what is documented is that, when the publisher Rupert Hart-Davis found himself short of money to pay Hassall, Linklater responded with typical gusto: ‘Lop it off my whack and give it me back sometime if circumstances warrant it and you can afford it. That’s all the agreement we need.’ The title story’s just twelve pages long. It has the perfect structure of a Victorian horror tale. There’s a nod to Edgar Allan Poe; it has fun with Freud and tai chi; and by the end there’s cod science about the pituitary gland’s anterior and posterior lobes. What makes it remarkable is that Linklater upends tradition. The sea’s the place of choice, not land. It’s a selkie superman capturing a woman, not a crofter trapping a melancholy fish-lady. The heroine’s horn-rimmed glasses are thrown in the sea: as she prepares to dive with Roger (‘I got the name from a drowned sailor’s pay-book’) he strokes her hair and tells her, ‘The waves when you swim will catch a burnish from you, the sand will shine like silver when you lie down to sleep, and if you can teach the red sea-ware to blush so well, I shan’t miss the roses of your world.’ True to form, the bookish narrator learns, too late, what he’s lost, as he listens to the selkie’s triumphant song: ‘the evening light was so clear and taut that his voice might have been the vibration of an invisible bow across its coloured bands.’ The best myths stick very close to human things – love, loss, jealousy, violence. Together, Linklater and Hassall reinvented something ancient, and did it extremely well. So I’m spoiled, as far as selkies go. Traditional versions of the story are awfully tame. And nothing’s complete without illustrations.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 43 © Morag MacInnes 2014

About the contributor

Morag MacInnes is a writer from Orkney. She once played the heroine of Linklater’s novel Magnus Merriman in a BBC Scotland radio production; but her Orcadian accent was considered to be something of a disadvantage.